for further information, please contact:

Rebecca Sheffield, Ph.D.

Senior Policy Researcher,

American Foundation for the Blind

rsheffield@afb.net

July 31, 2017

United States Senate Special Committee on Aging

G31 Dirksen Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

Chairman Collins, Ranking Member Casey, and members of the Committee,

Thank you for your invitation to provide feedback on the needs of older workers. The American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) is the leading national nonprofit envisioning a world of no limits for people with vision loss. AFB fulfills its mission to expand possibilities for people with vision loss of all ages through formulation and implementation of public policy informed by research, through professional and lay publications, and through development and evaluation of mainstream and assistive technologies. Along with its partners, AFB facilitates the Twenty-First Century Agenda on Aging and Vision Loss, which brings leaders and advocates together to shape better policies, programs, and supports for older adults with vision loss[1].

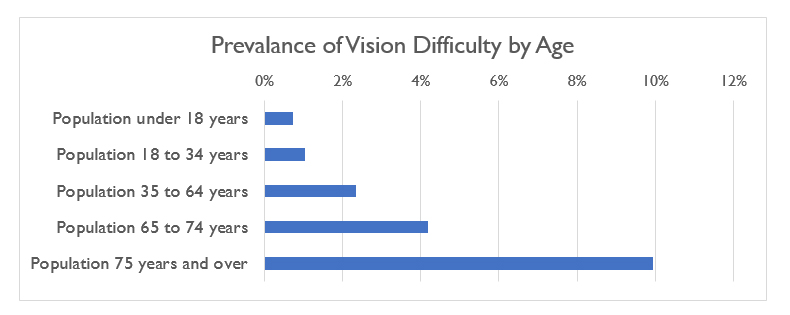

According to 2015 estimates from the American Community Survey [2], about 1 in 15 seniors aged 65 and up has "serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses or contacts." For seniors aged 75 and up, the prevalence is almost 1 in 10. Age-related vision loss occurs more often among people who are already disproportionality under-represented in the labor market, including women, minorities, and people of lower socio-economic status. Thus, it is imperative that any conversation about improving supports for seniors and the labor market be inclusive of considerations for seniors with vision loss.

Another important characteristic of the population of seniors with vision loss is the cooccurrence of additional disabilities. AFB's analysis of 2014 data from the National Health Interview Survey [3] found that 39.2% of adults (ages 18 and up) who self-reported having vision difficulty also had a cooccurring functional limitation (by contrast, of those who did not report having vision difficulty, only 13.1% reported experiencing a functional limitation). As well, when evaluating responses from all ages who reported having vision difficulty, 14.5% experienced difficulty hearing, too (only 4.2% of people without vision loss experienced hearing difficulties), and 13.5% of adults with vision loss experienced musculoskeletal problems (only 5.9% of people without vision loss experienced musculoskeletal problems). Thus, interventions and supports to increase employment options for people with vision loss must also be inclusive of people with additional disabilities.

What opportunities and challenges face older Americans [with vision loss] in the workplace?

Challenges

The most common causes of vision loss in the United States that typically occur later in life include cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma [4]. The onset of age-related vision loss can be seen in US Census data, beginning with people in their late 40s or early 50s. The typical older American with vision loss did not grow up receiving any special services or instruction about how to live independently with vision loss, and many older Americans rarely if ever met or worked alongside peers with visual impairment.

Frequently, individuals adjusting to vision loss believe that life as they know it is over, that their plans for the future have become impossible, and that their careers are at an end. Worse still, uninformed employers may perpetuate these beliefs by implicitly or explicitly discriminating against employees experiencing vision loss, including through job reassignment or forced early retirement.

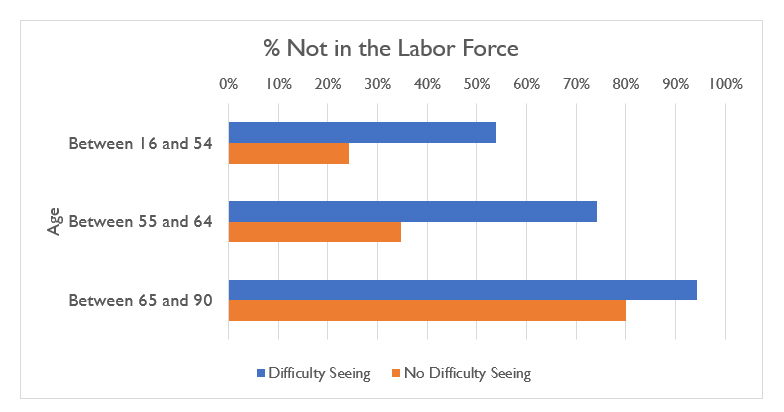

According to Current Population Survey data for the first six months of 2017[5], 78% of the civilian, non-institutionalized population with vision loss (ages 16 and up) is not in the labor force. Looking at the equivalent population without vision loss, 37% are not in the labor force - a gap of 41%. As presented in the chart below, further investigation reveals that this gap varies considerably by age. For ages 16 to 54, the gap is 30% (54% vs. 24%). For ages 55 to 64, the gap is 39% (74% vs. 35%). For ages 65 and up, 95% of people with vision loss are not in the labor force, versus 80% of their peers without vision loss - a 15% gap. This fluctuation demonstrates that people with vision loss are leaving the workforce earlier than their sighted peers and are significantly less likely to be working.

The onset of vision loss later in life can be daunting and can be made further challenging by biases and lack of knowledge on the part of colleagues, employers, and counselors. Older adults may be reluctant to identify themselves as having a disability (a common response is "I'm not disabled, I just don't see very well.") Furthermore, the eye doctors who diagnose progressive, age-related eye conditions often do not refer their patients to supports such as orientation and mobility training, independent living instruction, and low-vision support groups. This lack of self-identification and professional referrals, combined with limited awareness by the public of supports for people with vision loss, results in most older people with vision loss not receiving any supports to help them continue living and working independently in the manner they were used to prior to experiencing vision loss.

For older adults with vision loss returning to the labor force, navigating the application and hiring process can be a major barrier to employment. Recently, an adult in her 50's with an ocular-motor disability contacted AFB to describe her challenges in seeking a telework position: "About 90% of the jobs I found online only have online application processes and do not have a phone number to contact a recruiter to ask for an accommodation. It feels daunting to ask for an accommodation because the tests are standard procedure and the data is engineered to screen for speed and accuracy."

In the spring of 2015, a survey participant shared with AFB the need for assistance with job placement, recommending "more funding so retraining and job placement can be accomplished faster. I have been in the system since June 2014 and I have not been able to enter training or the workforce yet." Some rehabilitation agencies are not prepared to provide supports needed for older workers, and others do not have sufficient expertise in supporting persons with vision loss. For 2015, the Rehabilitation Services Administration reported that U.S. rehabilitation services agencies supported 34,265 people with blindness or visual impairment to find or retain jobs. Of these, 41% were under age 45, and only 9% were aged 65 and up.

Finally, perhaps the most significant barrier to employment for all seniors with serious vision difficulty is access to transportation. Multiple survey participants expressed that the cost of transportation in their area is prohibitively expensive; thus, they do not have sufficient access to transportation to access rehabilitation services or to return to work. A rehabilitation specialist in Arizona told AFB, "there are transportation difficulties as near as an hour outside of Phoenix, with no public transportation available for those no longer able to drive due to vision loss. The ability to continue working to supplement income is not available for people living in those areas."

Opportunities

With declining national unemployment rates in many parts of the country, employment opportunities are increasingly available, especially in growing fields like healthcare. Like all older workers, older Americans with vision loss bring years of experience and expertise to their career fields. Employers who make accommodations to enable seniors with vision loss to remain on the job may find that these accommodations - like better lighting or alternate format materials - are beneficial to a wide range of employees.

What best practices are employers implementing to create age-[and blindness/low vision]-friendly workplaces?

One example of a best practice for employers is the National Institute of Building Sciences Low Vision Design Committee's recently published Design Guidelines for the Visual Environment [6] . This document outlines recommended design principles for physical environments that increase access and safety for all people - especially people with visual impairments. The Guidelines include recommendations for lighting, signage, landscaping, and more, based on the combined expertise of vision, research, development, and design professionals.

An additional resource, the Department of Labor's National Technical Assistance and Research Center to Promote Leadership for Increasing the Employment and Economic Independence of Adults with Disabilities has published Employer Strategies for Responding to an Aging Workforce [7] , providing guidance for employers in recruiting and retaining older workers with disabilities. Among many recommendations, the authors endorse several best practices which would be particularly helpful in employing older workers with vision loss, including:

- Individualizing workplace ergonomics and analyzing job tasks to prevent injury and disability.

- Incorporating high- and low-tech assistive technology devices to increase, maintain, or improve functional capacity.

- Engaging older workers in discussions about creating accommodating workplaces.

- Offering on-the-job training for new skills and for renewing and refreshing essential skills, especially utilizing multiple, shorter training sessions with a range of training formats.

- Integrating wellness and health promotion for all employees.

- Being open to a range of work arrangements such as flexible schedules and telework, especially considering employees' transportation needs.

Most best practices for employment/reemployment of older adults will benefit older workers with vision loss, including best practices identified by the Government Accountability Office [8] and the Department of Labor's Office of Disability Employment Policy [9].

What steps should policy makers consider to help support older workers [who are experiencing vision loss]?

Economic security is even more precarious among older Americans who are likely to have had fewer employment opportunities or to have retired early due to unexpected vision loss. These individuals have become significantly economically disadvantaged as a direct result of their vision loss. In a recent survey, a respondent shared with AFB, "Many individuals were diagnosed after retirement and did not even think about planning to have finances to pay for video magnifiers, copayments for injections related to age-related macular degeneration; transportation, in-home assistance, or options for transportation. Those who do not have the financial resources - do without; those who have financial resources found that retirement funds have to be diverted from more fun/social expenditures to 'eye care needs.'"

The current Senior Community Service Employment Program (SCSEP) [10], provides community service and work-based job training for older Americans, but only those who have a family income of 125% of federal poverty level or below. Title V of the Older Americans Act should be amended to require that programs funded through Title V provide assistance to these individuals, regardless of income status.

Additionally, all employers should be encouraged to make available accommodations that enable employees experiencing vision loss to remain "in place" in their current occupations. Rehabilitation professionals working to support employers in providing accommodations should consider the following principles: Any modifications to the worksite…

- must include the employer's knowledge and approval,

- must be reasonable and avoid excessive costs or disruption to the business, as provided by the Americans with Disabilities Act and other disability civil rights laws

- must include training the employee with the skills to effectively utilize the accommodation.

Examples of accommodations might include…

- relocating a work station to maximize lighting and eliminate glare,

- providing a desk lamp to focus light on a work task,

- modifying the work schedule to accommodate public transportation schedules,

- exchanging some job tasks that affect productivity because of the disability with another employee,

- performing some or all the work from home,

- installing screen-enlarging software to enable a person with reduced vision to read computer screens, and

- installing screen reading software to give access to individuals who are unable to read text on a computer screen.

Finally, older workers with vision loss should have the same rights as their peers without visual impairments to plan for and enter retirement. For the many Americans who experience vision loss in their 50's, their plans for retirement may be thrown off course by time out of the workforce, unexpected expenses, and/or underemployment when reentering the workforce.

Moreover, in 2016, the U.S. Department of Education's regulations were amended to disallow states from using federal vocational rehabilitation dollars to provide vision-related rehabilitation services to older working-age adults for whom compensated work outside the home is not immediately achievable or sought. Therefore, a senior with vision loss who chooses to retire or pursue unpaid, volunteer opportunities may no longer have access to technology and/or ongoing supports he or she was receiving through a rehabilitation services agency. The Independent Living Services for Older Individuals Who Are Blind (OIB) [11] program can support some seniors but is not sufficiently funded to meet the needs of the growing population of seniors with vision loss who may wish to retire in the coming decades. Funding for the OIB program should be increased to support the growing population and to expand services to those who were previously receiving supports from vocational rehabilitation agencies.

Conclusion

AFB commends the Senate Special Committee on Aging for focusing its annual report on older Americans and the workforce, and we trust that the feedback provided in this comment letter is only the beginning of continued collaboration to support the Committee's review and evaluation of opportunities and challenges. While we have identified a handful of best practices, we hope that the Committee will concur with our assessment that much more research is needed to develop and identify strategies for communities, employers, and service providers.

All aging issues involve people with vision loss; likewise, all issues for people with vision loss have impacts on people who are aging. Even with the latest advances in care, anyone who wishes to live a long life has a good chance of encountering some symptoms of vision loss; most people can name older friends, colleagues, spouses, parents, or grandparents experiencing age-related vision difficulties. With the generation of aging boomers, our nation cannot afford to ignore any segment of the senior population, and AFB looks forward to supporting the research, systems, services, and policies which continue to offer equal opportunities and no limits for every American.

Sincerely,

The American Foundation for the Blind

[2] https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/15_5YR/S1810

[3] http://www.afb.org/info/programs-and-services/public-policy-center/research-navigator-a-quarterly-series-on-research-in-blindness-and-visual-impairment/research-navigator-intersection-of-health-and-vision-loss/1235

[4] http://visionproblemsus.org/

[5] Current Population Survey (January - June, 2017). Retrieved from DataFerrett http://dataferrett.census.gov

[6] http://www.nibs.org/?page=lvdc_guidelines

[7] https://www.dol.gov/odep/pdf/NTAR_Employer_Strategies_Report.pdf

[8] http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-07-433T

[9] https://www.dol.gov/odep/topics/OlderWorkers.htm