Despite my various disabilities and age, I am a productive, happy, and relatively healthy, self-sufficient person. I believe my life to be worth living. However, I fear that a healthcare provider will devalue my life because of their preconceptions about disability.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 65 to 74, with additional disabilities

The researchers were surprised to some degree that, during a pandemic, slightly more participants had concerns about transportation and social experiences than they did about healthcare. This may be a result of the data collection occurring in early April 2020, when the spread of the virus was not as high as it was during the later spring and summer of 2020. Despite this, healthcare concerns were still numerous for participants.

Of the 1,921 participants, 1,010 (54%) had concerns about healthcare due to COVID-19 and answered questions about this topic, 180 (10%) had concerns about healthcare but did not choose to answer questions, and 686 (36%) did not have concerns about healthcare.

The 796 participants who reported they had an underlying health condition were asked if they felt their health condition made them more vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were 466 (59%) participants with an underlying health condition who felt more vulnerable.

I have an irregular heart rhythm, and I'm scared that the virus will make my heart problems worse and cause complications. I am scared that no one will be able to advocate for me if I get very sick and require ventilator support.

—Congenitally VI Hispanic female, aged 25 to 34 years, with no additional disabilities

For those participants with mental health issues, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated their symptoms and limited their access to professionals. In addition, some participants raised concerns about the treatment they would receive should they need to be hospitalized due to COVID-19.

I'm afraid that I'll be denied services due to people not understanding my vision impairment or my mental health issues. ... With COVID, everything is changed and you are usually alone, which is horribly frightening.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 35 to 44 years, with additional disabilities

Participants provided their level of agreement to 17 concern statements.10

These statements were as follows:

- I am concerned about touching things in public, such as elevator panels, self-serve kiosks, or restroom doors to check signage. (n=939, M=4.23, SD=1.00)

- I am concerned that if I am hospitalized with COVID-19, that I will not be allowed to have a caregiver with me who would normally assist me with accessibility issues in a hospital setting. (n=812, M=3.68, SD=1.31)

- I am concerned about getting access to accurate and current information about those who may be infected in my area. (n=966, M=3.64, SD=1.26)

- I am concerned that I will not be able to care for someone living with me who contracts the COVID-19 virus. (n=729, M=3.63, SD=1.34)

- I am concerned because I am unsure how to maintain appropriate social distance (staying 6 feet apart from others) in public as I do not know how close others are to me. (n=907, M=3.56, SD=1.37)

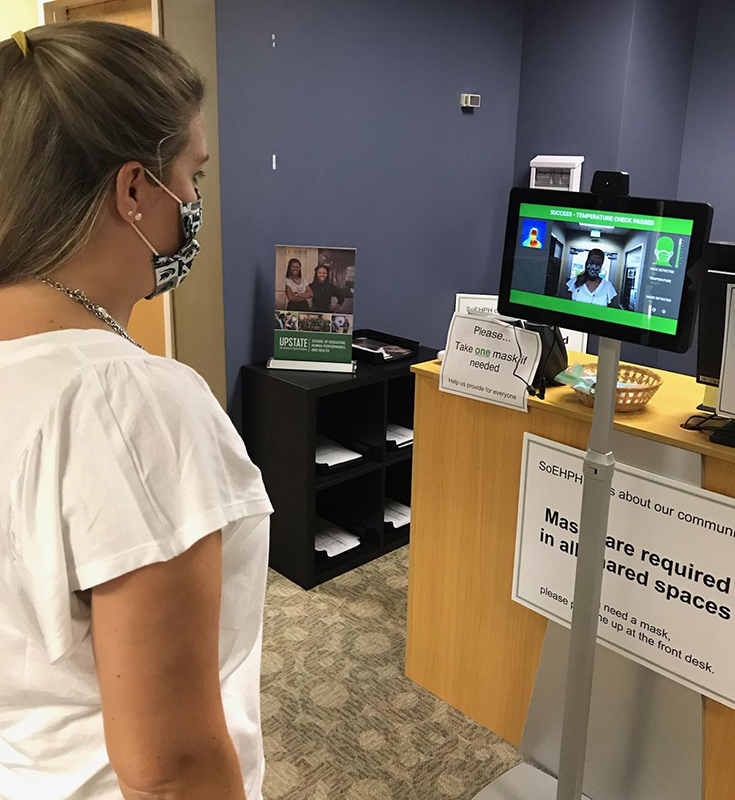

- I am concerned that I do not have an accessible thermometer to check my temperature. (n=920, M=3.56, SD=1.43)

- I am concerned because I do not want to ask someone to take my temperature and potentially expose them to COVID-19. (n=828, M=3.52, SD=1.38)

- I am concerned that I will not be able to maintain my eye care regimen (e.g., eye drops, injections, eye pressure checks, eye care appointments) during the COVID-19 pandemic. (n=586, M=3.46, SD=1.33)

- I am concerned that if I need care due to COVID-19, I will be denied access to care, such as a ventilator, because of my visual impairment. (n=968, M=3.41, SD =1.37 )

- I am concerned that I will not get the care I need if I get COVID-19 because of my other disabilities or underlying health conditions. (n=756, M=3.35, SD=1.35)

- I am concerned that I am not able to get to the pharmacy to get needed healthcare supplies/prescriptions. (n= 926, M=3.31, SD=1.30)

- I am concerned that I do not have someone to care for my family members if I have to go to work and a family member is ill. (n=433, M=2.96, SD=1.35)

- I am concerned I am not able to get to the pharmacy to request accessible labeling of medications. (n=748, M=2.94, SD=1.27)

- I am concerned about having access to information about how I can keep myself safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. (n=964, M=2.80, SD=1.28)

- I am concerned I am not able to meet with the pharmacist to review medication instructions. (n=856, M= 2.77, SD=1.22)

- I am concerned about my ability to adequately clean surfaces, such as kitchen counters, door knobs, or light switches. (n=946, M=2.73, SD=1.40)

- I am concerned that I do not have access to health insurance. (n=544, M=2.12, S D =1.19 )

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement: "I am concerned about touching things in public such as elevator panels, self-serve kiosks, or restroom doors to check signage." Of the participants who rated this statement more females (59%) than males (24%) expressed they agreed or strongly agreed, and those 55 years and older had the highest concern (38%) among the three age categories. Participants with a congenital vision loss (49%) had greater concern than those with a child- hood vision loss (13%) or vision loss during adulthood (22%). This statement was of higher concern to those who were blind (54%) compared with those with low vision (30%). There was no difference in the level of concern for participants by presence of an additional disability.

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement: "I am concerned because I am unsure how to maintain appropriate social distance (staying 6 feet apart from others) in public, as I do not know how close others are to me." Of the participants who rated this statement more females (45%) than males (18%) expressed they agreed or strongly agreed, and those 55 years and older had the highest concern (25%) among the three age categories. Participants with a congenital vision loss (39%) had greater concern than those with a childhood vision loss (9%) or vision loss during adulthood (14%). This statement was of higher concern to those who were blind (45%) compared with those with low vision (18%). There was a higher level of concern for participants who did have an additional disability (33%) compared with those who did not have an additional disability (30%).

When comparing the quantitative and qualitative data about healthcare topics, there is some discrepancy of what appears to concern many of the participants. Though the concern statement with the highest mean focused on touching things in public, comments about this concern were infrequent in the open-ended questions compared with other topics. Comments on topics participants most frequently provided focused on access to or perceived challenges they anticipated accessing COVID-19–related healthcare, necessary accommodations during a hospital stay, and the difficulties of maintaining social distance.

Access to Healthcare

Access to healthcare is a broad topic that includes ensuring one can obtain prescription and non-prescription medications and supplies, medical care related to COVID-19 or non-COVID-related medical issues, and COVID-19 testing.

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement: "I am concerned about getting access to accurate and current information about those who may be infected in my area." Of the participants who rated this statement more females (41%) than males (20%) expressed they agreed or strongly agreed, and those 55 years and older had the highest concern (27%) among the three age categories. Participants with a congenital vision loss (36%) had greater concern than those with a childhood vision loss (10%) or vision loss during adulthood (16%). This statement was of higher concern to those who were blind (39%) compared with those with low vision (21%). There was a higher level of concern for participants who did have an additional disability (32%) compared with those who did not have an additional disability (29%).

Medication and Healthcare Supplies

Many of the participants reported that they were able to get their medication or needed supplies through delivery services. In some instances, they were already using these services so there was no transition, whereas other participants discussed the need to investigate how to initiate at-home delivery. For some participants, being able to independently manage their own healthcare needs was hindered by websites and apps that lacked accessibility.

Even though I can have medications delivered, there is an ongoing problem with my ability to complete the process for doing this because of apparent issues with the app. Trying to contact support has resulted in long wait times, and inability of support to resolve the issue, though they claim the problem is resolved.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 45–54, with no additional disabilities

There were participants who had reason to go to the pharmacy. With the compounded challenges of transportation and social-distancing requirements, their ability to get their needs met was often hindered. Specifically, one systemic yet preexisting problem was related to the labels on the medication bottles. Some participants reported the labels of their medications were not accessible, whereas other participants were successful with requesting ScripTalk11 labels. Some pharmacists provided customers with large print or braille labels on their medications. A few participants indicated they were not aware of accessible options for reading medication labels.

I take one medication that is a controlled substance for sleep. It has to be picked up from the pharmacy. I asked if there was any way it could bedelivered since I am totally blind. They said I could come to the drive-through. I'm not sure what car they think I will drive.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 65 to 74 years, with additional disabilities

Many participants shared their concerns about accessible thermometers, specifically thermometers that do not rely on vision to be used. As a result of COVID-19, there were participants who could not find a thermometer to purchase, could not locate batteries for a thermometer they had as they often do not use standard batteries, had the thermometer break, or found that the thermometer was not accurate.

It is very frustrating not to have a talking thermometer. I have tried ordering one from multiple sources and being told that they are not in stock or they are very expensive.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 55 to 64 years, with no additional disabilities

Medical Care Not Related to COVID-19

In spite of stay-at-home orders and, for some, self-quarantine, participants had healthcare needs that in "normal" times would necessitate visits to healthcare providers for a routine check-up, surgery, cancer treatment, and other procedures. During April 2020, healthcare providers were focused on seeing patients only on an emergency basis. Thus, telehealth services were utilized more frequently by healthcare providers. Telehealth services allow a patient to use Internet access or a telephone to connect with a provider. Thirty percent (n=294) of 988 participants reported meeting with their healthcare provider using telehealth and 59 (21%) of 285 participants reported the telehealth platform was not accessible. The variability in telehealth systems is evident in the comments participants shared.

The telehealth visits are wonderful for sharing information. I'm very glad we have telehealth.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 25 to 34 years, with additional disabilitiesMy doctor's office uses the app Heallo. It is not very user-friendly for people who have to use a screen reader. I cannot send the doctor a message by myself, for instance. I would like to see changes made to the telehealth apps that need to be used by people with blindness and visual impairments.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 35 to 44 years, with additional disabilities

One area of healthcare that was especially alarming for some participants was not having access to eye care professionals. Some participants with low vision expressed concerns that they would lose additional vision as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

My eye appointment (which I feel is critical) has been postponed until further notice. In the meantime, my eyesight continues to get worse.

—Adult-onset VI White female, aged 35 to 44 years, with additional disabilities

Access to COVID-19 Testing

There were numerous participants who were concerned about their community only having testing options that were "drive through" for those who suspected they had COVID-19.

I live in [suburb of a major metropolitan city in the northeast]. I called one of the county numbers identified to ask how a blind person could get to a testing location or if someone could come to the home. The person said they did not know and gave me no additional referral to who might be able to help.

—Adult-onset VI nonbinary, aged 55 to 64 years, with additional disabilities

Access to Healthcare if One Has COVID-19

In spring 2020, there were daily news stories discussing access to ventilators for those with COVID-19. A few participants questioned why or whether disability would be a consideration of healthcare workers when making decisions about who did and did not get care.

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement: "I am concerned that if I am hospitalized with COVID-19 that I will not be allowed to have a caregiver with me who would normally assist me with accessibility issues in a hospital setting." Of the participants who rated this statement more females (40%) than males (20%) expressed they agreed or strongly agreed, and those 55 years and older had the highest concern (26%) among the three age categories. Participants with a congenital vision loss (33%) had greater concern than those with a childhood vision loss (11%) or vision loss during adulthood (18%). This statement was of higher concern to those who were blind (39%) compared with those with low vision (22%). There was a higher level of concern for participants who did have an additional disability (33%) compared with those who did not have an additional disability (29%).

There were numerous participants who reflected on societal views of disability and how COVID-19 was raising their concerns. The systemic challenge of people with disabilities being marginalized by many in the general public is not new. However, as resources are in short supply, it is not surprising that some participants raised this concern.

My concern runs deep relative to persons with disabilities being dismissed, disregarded, and or discarded as persons [who] lack in value when determining the level of attention/care to be given in health settings during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially when having to decide who receives use of limited resources.

—Congenitally VI Black or African American male, aged 45 to 54 years, with additional disabilities

Another concern of participants regarding potential hospitalization with COVID-19 was not having someone at the hospital with them who could assist as needed and advocate on their behalf.

Without someone to assist me and advocate for me, I'd feel like I was fighting the virus and a system that doesn't want me.

—Congenitally VI Hispanic female, aged 18 to 24 years, with additional disabilities

A systemic and pre-existing issue for those with visual impairments is that most of the material provided by healthcare providers is not accessible to them. Thus, the ability to read prescription labels, pre-surgery instructions, and directions is problematic. Participants anticipated that this lack of accessibility coupled with lack of staff availability and crowded hospitals would potentially decrease their care.

We need accessible healthcare mobile apps and websites. We need technology to represent graphical information in a format we can understand.

—Congenitally VI White male, aged 45 to 54 years, with no additional disabilities

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement: "I am concerned that I will not be able to care for someone living with me who contracts the COVID-19 virus." Of the participants who rated this statement more females (40%) than males (21%) expressed they agreed or strongly agreed, and those 55 years and older had the highest concern (26%) among the three age categories. Participants with a congenital vision loss (34%) had greater concern than those with a childhood vision loss (9%) or vision loss during adulthood (17%). This statement was of higher concern to those who were blind (40%) compared with those with low vision (19%). There was a higher level of concern for participants who did have an additional disability (32%) compared with those who did not have an additional disability (29%).

Recommendations

Survey participants reported concerns about healthcare access during the COVID-19 pandemic that were both related to health practices to control the virus and derived from pre-existing systemic issues. Leaders developing response procedures for any emergency need to consider all populations, including those with disabilities, gender orientation, ethnic backgrounds, economic status, etc.

- Those with visual impairments and others who do not have access to a vehicle, must have more than one way to access a testing site. Alternative options may include in-home testing or communities providing safe transportation to get to a testing site.

- Hospitals, doctor's offices, and other healthcare facilities must recognize that people with visual impairments may need someone to accompany them who can visually interpret the environment when necessary, advocate on their behalf, and provide alternatives when information is not accessible. Federal law requires hospitals and state agencies to modify policies to ensure patients with disabilities can safely access the in-person supports needed to benefit from medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic.12

- Healthcare providers should make written information accessible to patients who are visually impaired by providing electronic, braille, and large print options. Should alternative options be unavailable, then it is the responsibility of medical staff to review the material with the patient to ensure equivalent access.

- Designers of telehealth tools should ensure they are accessible to all users who are visually impaired. Electronic health records, secure video platforms, and other telehealth systems should meet the highest accessibility and usability standards.

[T]here is no definite answer for those needing to test, yet cannot drive to testing site. Providers and the lawmakers seem to assume everyone drives, and are not addressing this question.

—Congenitally VI White female, aged 65 to 74 years, with no additional disabilities

- Medical providers using telehealth can designate workers who can meet with patients who are visually impaired prior to their visit to ensure that time with the healthcare provider is used efficiently. Clearly labeled buttons within apps or websites, directions on how to position the device's camera, and an accessible platform for messaging, note taking, and reviewing test results are essential.

- Medical providers may need to allocate additional time to assist patients who are visually impaired with properly aligning the camera on their device and taking advantage of other features available through telehealth platforms.

- Companies that produce accessible thermometers and other medical equipment need to ensure that they are accessible, reliable, easy to use, standardized, and widely available.

- Prescription labels and directions need to be available in accessible format to allow the patient independent access. ScripTalk13, large print, or braille labels are options that are low cost and can be used to ensure those with visual impairments can independently manage their medications.

10. The mean (M) is derived by averaging the participants' ratings, strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The larger the standard deviation (SD) the greater the spread from the mean of the participants' ratings.

11. https://www.scriptability.com

12. 45 CFR §92.202 Provides for effective communication for people with disabilities. 45 CFR §92.202 requires covered entities to provide reasonable accommodations unless the accommodation results in fundamental alteration to the program or activity. Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Race, Color, National Origin, Sex, Age, or Disability in Health Programs or Activities, 45 CFR §92 (2020).