"In-person interviews are very awkward because some people don’t like guide dogs. Filling out paperwork is very difficult and asking for assistance makes me feel inadequate.…When applying to federal or state jobs, it is difficult to reach someone to receive reasonable accommodations for online tests." —Asian/Asian American female in her 20s who is congenitally visually impaired

The Hiring Process

During the hiring process, many individuals who are blind, have low vision, or are deafblind carefully consider when, or if, to disclose their visual impairment to the potential employer and how to request accommodations, and each individual has a different level of knowledge of their rights and responsibilities. Individuals are not required to disclose their visual impairment, but they may be required to provide information about their functional limitations or reasonable documentation that they are an individual with a covered disability when requesting accommodations. Of 323 participants, 270 (83.6%) reported they disclosed their visual impairment during the hiring process. Most often, disclosure occurred during the interview (n=74), in the cover letter or resume (n=59), when completing the job application (n=36), or when scheduling the interview (n=30). Some participants had disclosed their visual impairment prior to applying for the position through means such as personal contacts within the organization or having completed volunteer, internship, or prior work with the organization.

Rights and Responsibilities Until a job offer has been extended, the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 do not allow employers to ask an applicant about the nature or condition of their disability. Employers may ask whether the individual will require an accommodation and what type if they voluntarily disclose. After the job offer has been made, the employer may ask additional questions of future employees with disabilities for the purpose of providing accommodations and determining whether the disability poses a direct threat to health or safety. In general, employers may not discriminate if the employee can safely perform essential job tasks with or without a reasonable accommodation.

For more information on employers’ responsibilities, see "Blindness and Vision Impairments in the Workplace and the ADA" published by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

In an open-ended question, participants were asked what reaction, if any, they received after disclosing their visual impairment. Several participants worked in the field of visual impairment and reported that there was no reaction to their disclosure of their visual impairment since hiring managers already knew or were seeking a candidate who was blind or had low vision. Some participants also indicated that the company they were seeking employment with was pleased to learn of their visual impairment because it was open to hiring people with disabilities or because it valued employees with diverse backgrounds. Participants also indicated that their visual impairment was a nonissue as long as they could perform work tasks required in the job description. A few participants also reported that employers had questions about how they performed tasks and were surprised at what they could do because employers had never seen the use of Assistive Technology (AT) to perform tasks which they thought could only be done using vision.

The 53 participants who did not disclose their visual impairment were asked in an open-ended question to explain why they did not do so. These participants reported they wanted to get their foot in the door first and previous experience had taught them that if they disclosed their visual impairment early, they would be denied that opportunity. One reason provided by one participant is the fact that the population they work with is not accepting of people with disabilities, has negative attitudes and would possibly discriminate against them. Several participants elaborated on this in the interviews and explained that they worked remotely with people from countries where disability is typically viewed more negatively and legally treated differently than in the United States. Other participants also said there was nowhere on the application to disclose their visual impairment and the process did not seem conducive to offering this information because of time constraints or lack of individual attention to the job candidate.

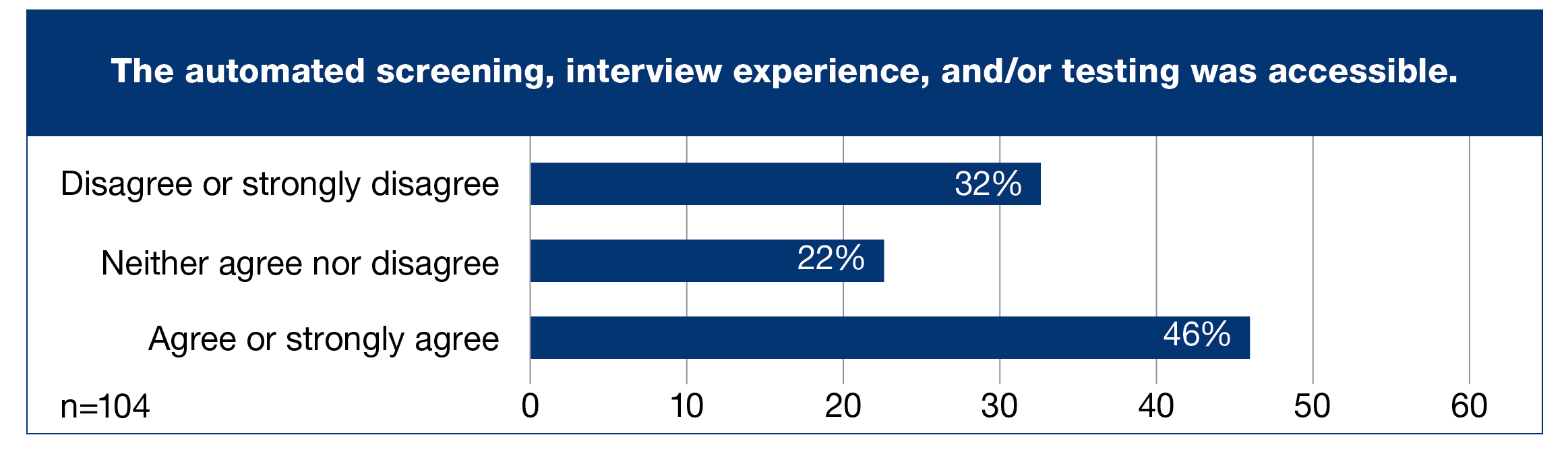

Almost a third of the 323 participants (n=105) reported that part of the hiring process for their current job involved an automated process in which they had to complete a screening, interview, or testing using a computer. Figure 1 shows how participants viewed the accessibility of the hiring process.

The participants were asked to select their level of agreement with the statement: The automated screening, interview experience, and/or testing was accessible. Of the 104 participants who responded, 33 (31.70%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement, indicating some degree of inaccessibility for 3 out of 10 candidates.

Figure 1. Accessibility of Hiring Process

"At [a university], I needed to take an automated test with a monitor that was secured at the back of the table and was very small. It was a timed test. I tried to talk with the director of employment who was not amenable to adaptations, [who said] I would then have a leg up on the other applicants. I brought suit against the office and won the case. Afterward, the office asked if I could help them make the office more accessible, which I did. But I never did get a job at [the university]. I did get a letter of apology from the Executive Vice Chancellor." — White female in her 60s who is congenitally visually impaired

Participants described the accessibility challenges they experienced with automated systems. These included a variety of challenges such as difficulty keeping up with timed assessments, incompatibility with screen readers, small fonts, needing to respond to pictures during the assessment, or needing to take the test on a computer without screen reader software or screen magnification software installed. However, some participants reported positive experiences working with these automated systems.

Fifty-eight of 323 participants reported that as part of the interview process for their current job, they were asked to demonstrate their technology competence, for example, by taking a typing test or showing how they used a specific software program. Of these, 36 participants requested accommodations, such as being allowed to use their own computer for the test, to use screen reader software or a larger monitor at the worksite, or to be given extended time. These requests were usually granted. Additionally, 53 participants chose to give reasons why they did not ask for accommodations. These reasons included using their own equipment (n=29), not requiring accommodations (n=9), believing that if they requested accommodations, they would not get the job (n=4), not wanting to call attention to their visual impairment (n=3), and believing the employer would not be able to provide the accommodations (n=3). Several participants indicated that they did not need to request any accommodations during a technology competence test because their employer, having had experience with workers with visual impairments, made all processes accessible. One participant completed the demonstration of competency from home and therefore already had their AT available.

Onboarding

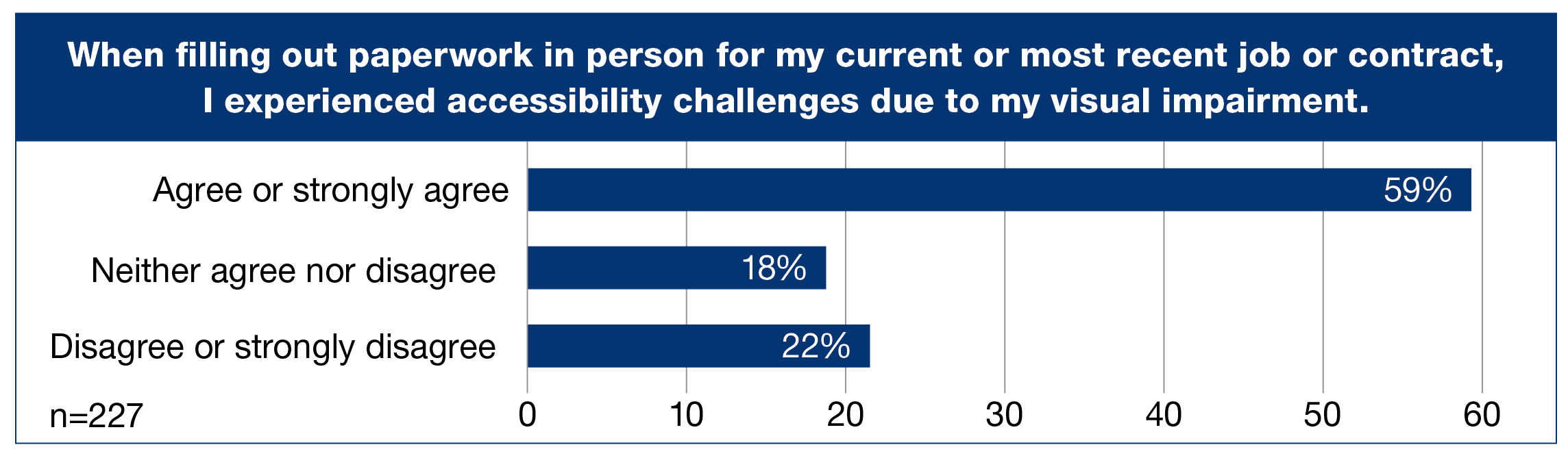

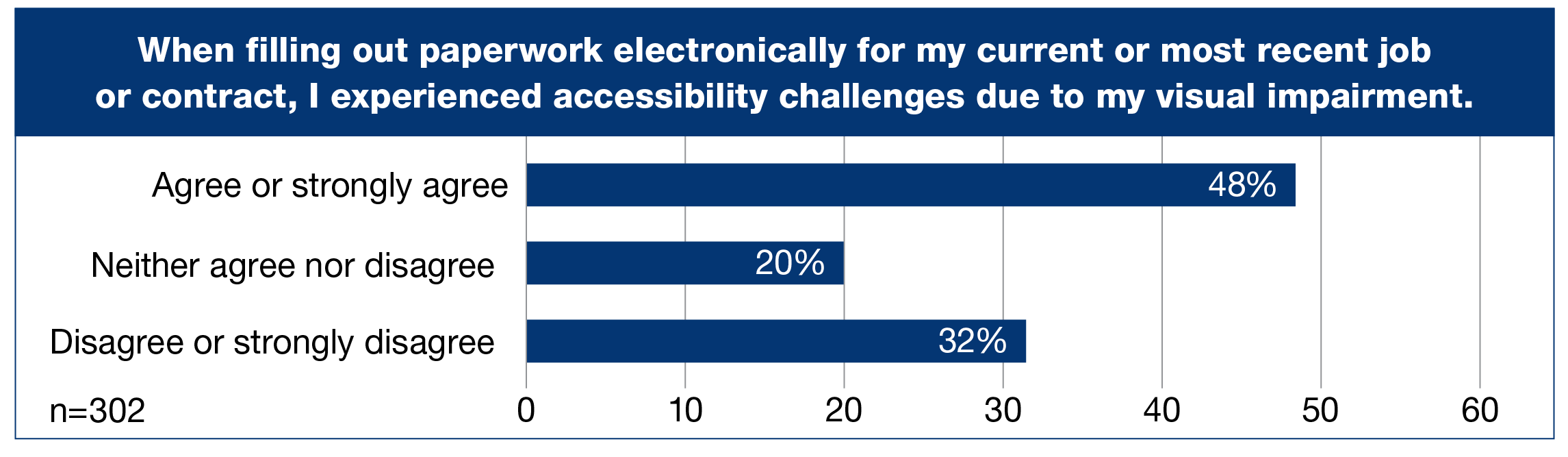

Participants reported completing typical onboarding activities such as filling out paperwork and setting up their email account. They were asked to rate the accessibility of the paperwork they needed to fill out. Figures 2 and 3 show how participants experienced accessibility challenges when filling out paperwork in person and electronically.

Participants were asked to select their level of agreement with the statement: When filling out paperwork in person for my current or most recent job or contract, I experienced accessibility challenges due to my visual impairment. Of the 227 participants who responded, 134 (59.0%) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, indicating that they experienced accessibility challenges when filling out paperwork in person.

Figure 2. Experienced Challenges When Filling Out Paperwork in Person

Participants were asked to select their level of agreement with the statement: When filling out paperwork electronically for my current or most recent job or contract I experienced accessibility challenges due to my visual impairment. Of the 302 participants who responded, 144 (47.7%) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, so almost half of those going through onboarding experienced accessibility challenges with online paperwork.

Figure 3. Experienced Challenges When Filling Out Paperwork Electronically

Participants were more likely to experience accessibility challenges with paperwork they needed to complete in person than when filling out paperwork electronically.