I’m very worried [children birth to 3] are all falling through the cracks during this time —Multiracial male family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2.5 to 3 years old

In the United States under the IDEA Part C, children from birth until age 3 years with disabilities who meet specified criteria are entitled to early intervention services. The IFSP is the document developed to serve as a blueprint for the information, supports, and services the child and family receive from members of the educational team. IDEA stipulates that early intervention services are to be delivered in the natural environment, typically the home or day care center. In Canada there is no equivalent national law to IDEA that regulates the provision of early intervention services.

Decisions for how, if at all, early intervention services are delivered are made at the provincial level.

There were 62 children (U.S. n=56, Canada, n=6) in the survey who were receiving early intervention services. In this section, data are not broken out by country of residence. The children’s ages and descriptive characteristics are reported in Table 3.

Table 3: Ages and Descriptive Characteristics of Children Receiving Early Intervention

| AGE: | Total (n=62) | Blind (n=8) | Low Vision (n=15) | BL + Additional Disabilities (n=10) | LV + Additional Disabilities (n=29) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth–1 Year | 11 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 1 Year + 1 Day–2 Years | 14 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| 2 Years + 1 Day–3 Years | 37 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 21 |

Family members were asked about the early intervention services received by their children prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, using March 1, 2020 as the start date for the pandemic. Prior to this date, children were receiving between 1 and 9 early intervention services. The most frequently received service was from a TVI (n=48), followed by an early intervention specialist/development specialist (n=38), an occupational therapist (n=32), a physical therapist (n=32), and a speech therapist (n=26).

Sixty-two family members reported multiple ways in which their child received early intervention services from educational team members before changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These included having an early intervention team member:

- Come to the home or the home of the person caring for the child (n=43)

- Come to the child’s day care (n=12)

- Meet with the family member and child at a location where the child attended an individual session (n=9)

- Provide services to the child during a group session (n=8)

- Meet with the family member and child through tele-intervention (n=3)

Fifty-six family members reported the frequency with which their child received early intervention services prior to March 1, 2020. Twenty-seven families received services two or more times a week, 13 families received services once a week, 7 families received services twice a month, 6 families received services once a month, and 3 families reported other schedules.

Changes in Early Intervention Services and the Impact on Children and Families

Twenty-nine family members described how the frequency of the early intervention services changed for their family during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fourteen family members reported no change in service time. Fifteen family members reported a decrease in services. Fourteen family members described changes in service delivery, for example, changing to online or phone service. For the 31 family members whose child was continuing to receive early intervention services, the five most common ways services were delivered were:

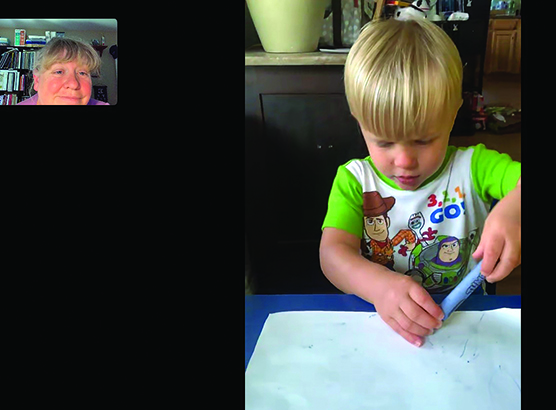

- Meeting with educational team members online, for example, through Zoom or Google Hangouts (n=21)

- Receiving recommendations of websites, videos, or other online resources (n=19)

- Receiving emails with ideas and activities (n=15)

- Receiving materials or toys through the U.S. Postal Service/Canada Post or by an educational team member delivering them (n=19)

- Receiving telephone calls from educational team members (n=7)

Family members were asked about the level of communication they had with their child’s educational team members. Of the 52 family members who responded, 2 had no communication, 12 had little or limited communication, 24 had the same level of communication, and 14 had increased communication.

For some family members, the shift to online service delivery allowed them to spend more time with their child. In addition, they were able to see firsthand the positive effect of therapy and instruction on their child.

[D]oing this virtually is hard; my son is normally seen in day care. It’s nice that they 'see' him in my home.…[N]ew ideas for old problems in my home are created. LOVE my team. —Black or African American female family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2 to 2.5 years old

A shift in early intervention service delivery meant an adjustment not just for adults, but for children, too. Not all children had a positive reaction to the changes in how they received early intervention services.

Without [a] structured schedule and activities, it’s been difficult to motivate learning. Keeping her attention span and focus has also been a problem. —White female family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2.5 to 3 years old

Some family members had children who were being evaluated by one or more educational professionals. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, evaluations ceased, and this caused stress and uncertainty for family members.

With some therapies stopped due to COVID-19, family members were concerned about their child’s developmental progress.

Family members were asked to select their level of agreement with the statement: I believe my child is continuing to make developmental progress in the same way they would if there had not been a change in how early intervention services have been provided to our family. Of the 54 family members who responded, the mean was 3.35 (SD=1.28) 13. The level of agreement family members had with this statement fell between “Neither agree nor disagree” and “Agree.” Two months into the pandemic, it is positive to see that many family members believed their child was progressing in their development.

All outpatient therapies have been canceled until further notice. I feel my son is falling behind in speech, which he only receives as [an] outpatient. —White female family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2.5 to 3 years old

Many family members were unsure of the impact the changes in service delivery due to COVID-19 would have on their child’s development long term.

I am also concerned about the social development that she is not getting with age-appropriate peers due to stay-at-home orders. —Hispanic or Latina female family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2.5 to 3 years old

A key tenet of early intervention is to provide family members with support as they learn to navigate having a child with a disability. Support necessitates communication between family members and early intervention providers. Family members were asked about the level of support they were receiving from their child’s educational team members. Of the 54 family members who responded, 3 had no support, 11 had little or limited support, 26 had the same level of support, and 14 had increased support. Support also means that families receive the services stipulated on the IFSP. This was not always the case according to a few family members.

[W]e have not been provided with services promised before the pandemic. I am being expected to provide four therapies on top of everything else. —White female family member of a child who is blind, 6 months to 1 year old

Yet, other families felt supported through online service delivery to their family.

There is more focus on what I can be doing as a parent to support my child, which is appropriate and appreciated. I think this is the way services should be happening ongoing. Previously our services were taking place at day care so we were not as involved, so telehealth has given us more opportunities to connect with our child’s provider. —White female family member of a child with low vision, 1.5 to 2 years old, and a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 6 years old

Balancing Multiple Roles

For many family members, the challenge of balancing multiple roles was at times overwhelming. Family members who were employed had to balance their professional work with the new role of teacher/therapist. When families had more than one child in the home, the stress was compounded.

Online instruction was challenging for many families. Family members reported that it was not always easy for them to make the time for meetings, young children were not accustomed or capable of participating in screen time, work schedules were in conflict with educational schedules, and other family demands competed with educational demands.

It’s been really hard as my son can be loud. I schedule all the virtual lesson[s] during my lunch hour or after I get off work. I’ve been amazed that the team is ok meeting at 5 sometimes. I try to work only in one room of the apartment, so the rest of the apartment is family time. —Black or African American female family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2 to 2.5 years old

Family members were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement: I believe that I am not living up to the expectations of my child’s early intervention team because I cannot complete everything they are asking me to do with/for my child. Of the 52 family members who responded, the mean was 3.02 (SD=1.28). Most family members rated this statement as "Neither agree nor disagree." The uncertainty many family members had about the expectations of educational team members is concerning and points to the importance of the need for clear communication.

Access to Resources

Most family members turn to professionals for guidance with their child since few family members have any experience with children who have visual impairments and/or additional disabilities. It is essential for family members to have access to resources, supplies, and information on the best way to support their child’s development. Many family members reported that the educational team members were not able to provide the support, resources, and information their family needed during the pandemic.

I think this is especially more of a challenging time for visually impaired students. For kids like mine, distance or online learning is just not the same or comparative to in-person learning. I don’t think there are enough resources for children with visual impairments. —White female family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2 to 2.5 years old

Children with visual impairments benefit from access to specialized materials designed to meet their unique needs. There were a few family members who did not have the materials they had been told they would receive prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We were supposed to be provided with some tools for our son such as a resonance board and a ‘little room’. They said due to COVID these things will not be provided and [they] offered some ideas to make things from stuff we have at home. I have three kids and my husband is still working. I did not have the time to build anything suggested to me. We were really counting on the provided materials. —White female family member of a child who is blind, 6 months to 1 year old

Transition to Preschool

There were 20 family members who had a child over 2.5 years of age, the time at which transition to preschool typically ramps up. Before March 1, 2020, 16 of the 20 family members indicated that a plan was in place to begin the transition of their child to preschool. When asked if they had concerns about their child’s transition to preschool, 5 family members did not have any concerns about the transition, 6 family members were unsure about how the transition would occur if schools were closed, 1 family member tried to contact someone about the child’s transition with no success, and 1 family member was unsure who to contact. Four family members selected “other” and described feelings of uncertainty and anxiety in their written explanations.

My daughter was supposed to begin preschool at a local children’s school for visually impaired children. Due to COVID-19, she will not be attending for many months as they are closed to in-person school. I’m concerned she is going to fall even further behind her same age peers now. —White female family member of a child with low vision with additional disabilities, 2 to 2.5 years old

Recommendations

Early intervention services are designed to provide families with supports, resources, and guidance as well as direct instruction to enable children to learn and grow. With the quick shift in the way early intervention services were provided from in-person interaction to virtual supports, it is not surprising that many family members raised concerns. The following recommendations should be considered as providers, administrators, policymakers, and most importantly, families, support the growth of children with visual impairments during their first 3 years of life.

Family Support

- Family members of children receiving early intervention services would benefit from an online community that allows them to connect with each other for support, sharing of resources, and problem-solving how to balance all the demands placed on them. Such a community needs to be accessible, ensure privacy, promote respect, and provide accurate information.

- Professionals can invite families to join support groups that meet virtually. Providing both online and telephone access can enable families without Internet access or an available device to have the option to call in and equally participate.

Role of Professionals

- Professionals must establish clear communication and timelines so families are informed and assured of how evaluations, IFSP meetings, and/or transition planning for preschool will occur, including information on the correct individual to contact for each service.

- To best serve children and families, professionals must establish the most effective way to communicate with each family, demonstrate and model techniques, assess the child’s growth, and offer supports. Clear communication includes stating expectations for what can and cannot be delivered remotely and what role the family members may assume.

- In selecting resources to share with families, professionals should review the resources to ensure that the information they contain is up to date, model best practices, and are family friendly. Consideration must also be given to the family member’s reading level and attention span, in addition to ensuring materials are inclusive of diverse family values and perspectives.

- Professionals should communicate with families to address their concerns and fears regarding their child’s progress and the effect of the change to remote instruction.

Considerations for Administrators

- Administrators must ensure that professionals have the capacity, resources, and tools to evaluate children, hold IFSP meetings, and plan for transition of children to preschool.

- Administrators must be flexible in allowing service providers to adjust their schedules to enable them to meet with families in the evenings or on weekends when many families are more available and children may be more receptive to intervention.

- Administrators need to allow time and provide encouragement to staff, so they can establish open communication between themselves and family members. This will allow professionals to support the development of infants and toddlers with visual impairments more effectively.

- Many children require access to equipment such as specialized seating, pre-braille materials, or adaptive mobility devices. Mechanisms must be set in place so that families can have access to necessary materials whether this be through staff making contactless deliveries, families being asked to pick up items from a centralized location, or materials being sent via U.S. Postal Service, Canada Post, or another delivery service. The purchase of additional materials may be required if they were previously shared between students.

Considerations for Policymakers

- Recognizing that there are many uncertainties for the 2020–2021 school year, U.S. state and Canadian provincial policymakers may wish to extend early intervention eligibility for children beyond their third birthday. This will allow service providers who know the child and family to continue providing support and services without introducing a new educational team to the child and family.

- Funding must be allocated to allow for the establishment of a one-stop shop for resources for both families and professionals. For example, the website, WonderBaby, previously provided resources to family members and professionals and focused on children with visual impairments receiving early intervention services.

- Future budget requests must include adequate money for early intervention providers’ salaries, equipment, and programming for children and families.

- When early intervention services are moved from in person to online, the platform used must be fully accessible to families, which may include a member with a disability.

13. The mean (M) is derived by averaging the participants’ ratings—from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5). The larger the standard deviation (SD), the greater the spread from the mean of the participants’ ratings.