March is Women’s History Month, typically a time to encourage the celebration and study of the vital role of women in American history. But this year, parents and teachers around the world are confronting uniquely challenging circumstances, as schools face unprecedented closures to combat the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. At AFB, we have pulled together some accessible online resources that honor 7 blind women whose lives span from 1829 to 1985, and whose histories are largely forgotten. We encourage your 6th to 12th graders to read about these women and participate in Women’s History Month from home. Their stories are fascinating, educational, and will keep them occupied!

When we think of blind women, most of us think of Helen Keller, blind and deaf after an illness at 19 months of age. Keller became internationally known as a champion for those with vision loss and a fighter for the disenfranchised. Her fully accessible digitized archival collection is a font of information about her life for scholars, K-12 students, and the general public.

But there are so many other interesting and important blind women who have left their mark on American history as well, and who have never received the press and celebrity status that Keller enjoyed. Here are just a few that we think you should know about.

Laura Bridgman (1829-1889)

Laura Bridgman was the first deafblind student Perkins School for the Blind successfully taught. She arrived at the school in 1837, when she was just 7 years old. Once she mastered communicating through finger-spelling, she went on to study reading, writing, geography, arithmetic, history, grammar, algebra, geometry, physiology, and philosophy.

Helen Keller talked about meeting Laura Bridgman in a 1905 letter to F.W. Jerusalem (we believe this is Annie Sullivan’s handwriting): “I remember meeting Laura Bridgman when I first visited Boston. I was only a little girl, and I had four opportunities to talk with her.”

Explore Laura Bridgman’s Journal and Other Writings in the Perkins Archives.

Adelia M. Hoyt (1865-1966)

An American librarian and author, Adelia Hoyt was an early advocate of the “nothing about us without us” philosophy. "Our most successful workshops and homes have been planned and supervised by sightless persons," she explained, and "every organized effort for the welfare of the blind should have on its board of directors some competent sightless person or persons" to prevent "many a sad mistake."

Hoyt had recurrent fevers in childhood that caused significant vision loss. She attended the Iowa School for the Blind, and became a librarian at the Library of Congress's Reading Room for the Blind. She was coauthor, with Gertrude T. Rider, of Braille Transcribing: A Manual (1925), which they created to guide volunteer transcribers after World War I—a service that was later taken over by the Library of Congress, where Hoyt served as director of braille transcribing.

In 1930, Hoyt testified before a Congressional committee in support of the Pratt-Smoot Law, which created federal funding for braille books. She trained and certified more than 2,000 volunteer braille transcribers over the course of her career. In 1940, Hoyt received the Migel Medal for Outstanding Service to the Blind. Helen Keller presented the award to Hoyt at the offices of the American Foundation for the Blind, where she acknowledged Hoyt’s work in a speech.

Her memoir Unfolding Years: The Events of a Lifetime is now in the public domain, and available through the Internet Archive.

Anne Sullivan (1866-1936)

Many know the story of Helen Keller’s beloved “Teacher,” whose pioneering work with Helen Keller became the blueprint for education of children who were blind, deafblind, or visually impaired. Fewer know that Annie Sullivan was legally blind herself.

When Anne was 7 years old she developed trachoma, a bacterial infection of the eyes. This infection went untreated and affected her vision. She had almost no usable sight until she had an operation at the age of 15, which restored some of her vision, but she remained visually impaired for the rest of her life.

Learn more about Annie’s life in AFB’s online museum Anne Sullivan Macy: The Miracle Worker, and read her beautifully written letters to Helen Keller in the digital Helen Keller Archive.

Tilly Aston (1873-1947)

An advocate for change, Australia’s first blind teacher, and an eloquent writer with a pioneering spirit, Aston dedicated much of her life to helping her “sightless brethren” in their pursuit of equality. Aston successfully created the first library of braille books in Melbourne, recruiting sighted stenographers and teaching them braille so they could convert printed text into braille books.

Her advocacy included achieving the right to vote and free public transportation for people who are blind, and securing government approval for pensions for all legally blind people. Aston also successfully lobbied for the world's first free postal system for braille—and, later—Talking Books. Watch this video created by Culture Victoria, Australia, where relatives and historians discuss the life of Tilly Aston.

Her memoir, written in 1935 and published in 1947, is available through the Internet Archive.

Georgia Duckworth Trader (1876-1944)

Georgia Duckworth Trader was born with congenital cataracts, and lost her vision completely when she was 11 years old, due to an unsuccessful surgery. But her mother was determined that Georgia would not be deprived of an education, and Georgia became the first blind student ever to be admitted into a Cincinnati public school. That passion for education was to be a constant in her life. She and her sister Florence taught braille classes at the Cincinnati Public Library, and established the Cincinnati Library Society for the Blind in 1901. In 1903, they opened the first home for blind women in Ohio, which later grew into the Clovernook Center for the Blind and Visually Handicapped.

Georgia and Florence Trader received the Migel Medal from AFB in 1944 for their work teaching students who were blind or visually impaired. Georgia Trader took great pleasure in working with adults who had lost their sight later in life. One of her students was a sixty-year-old woman who was born deaf and could not talk and now was blind. A friend named Mona Downs later wrote, “It was extremely difficult to make her understand that she was to be taught to read with her fingers. Some said it could not be done, but Georgia felt it could be accomplished. So she kept trying week after week and finally the woman’s face lighted up and the awakening had come, she realized what we were trying to do” and she learned braille.

Martha Louise Morrow Foxx (1902-1985)

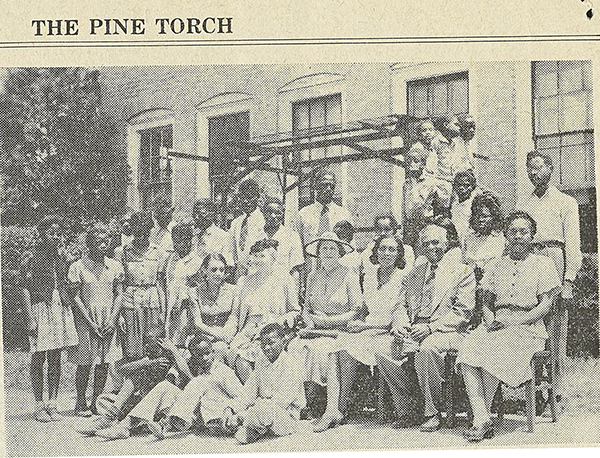

Born in North Carolina, Martha Louise Morrow lost the majority of her sight in infancy. After earning her Bachelor of Science degree in education from Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia, Foxx helped open Mississippi’s first-ever school for black students who are blind—the Department for the Blind on the campus of the Piney Woods Country Life School—serving as teacher and housemistress for all of the students, and later becoming its first principal.

An innovative educator during a time when schools were still segregated by law, she believed in hands-on teaching and learning, community-based lessons, independent living, braille, music, the arts, work experience, and vocational opportunities—many of the principles of the expanded core curriculum now followed today in teaching students who are visually impaired.

(Photo description: group photo from a Helen Keller visit to the Piney Woods School in 1945. Ms. Foxx is seated in the first row, far right. Image taken from Piney Woods publication The Pine Torch, 1945).

Geneva Harrison Washington (n.d. - please let us know if you have information!)

In 1964, Ebony profiled Geneva Washington, a clinical social worker who worked with veterans with mental trauma.

Washington attended Howard University, earned a master's degree in social work, and received a scholarship from AFB along the way! But her path to employment was “grueling work and often heartbreaking,” she said. “I started out by making appointments for job interviews over the telephone, mentioning neither my blindness nor color. But I got so many rejections when I appeared in person, I changed my tactics. I finally decided a prospective employer could only say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ so I steeled myself for either. My one ambition was to work for a sighted agency. I didn’t want to be pushed into an agency for the blind.”

She achieved that goal when she found employment as a social worker at the Veterans Administration’s New York City regional office, interviewing at least 25 patients a week and taking notes with her braille slate and stylus.