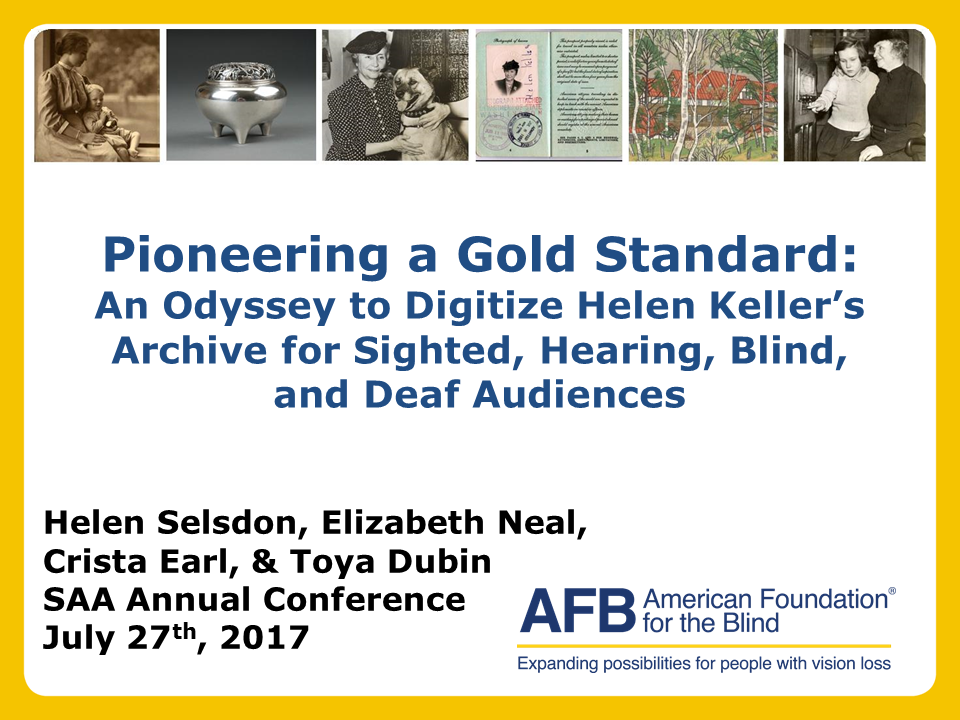

We were so honored today to present at the Society of American Archivists 2017 Annual Meeting to discuss the Helen Keller Archive digitization project, and our work to create a fully accessible archival collection. Our topics included:

- Why we were doing it, and why you should, too!

- The process of digitizing braille, and other tricky materials

- Metadata—all the information about the information that is contained in the collection (archivists love that stuff)

- How to make websites accessible

- How to conduct usability testing, and why you should bother

- What we learned, and how we changed the site accordingly

We had some wonderful questions from the audience after today's presentation, and wanted to share them with you.

What platform are you using?

Veridian has been a wonderful partner in this project, and we asked them for a lot of customization of both the user end and the administrative interface.

Originally, Veridian's platform did not have a transcription interface. Hudson Archival worked with them to build that in, and Veridian enhanced the transcription functions radically to support our volunteers' needs. The transcription platform allows the volunteer to see the item that he or she is transcribing side by side with their transcription data. For people correcting the errors that so commonly occur in optical character recognition (OCR), the tool highlights the area that you are working on as you correct it.

Veridian has significantly enhanced the administrative functions over the course of this project, so that an administrator can track the transcribers' work, and easily assist if problems arise.

What work flow did you develop for transcription?

AFB staff developed a set of transcription standards that would lead to a good user experience for people using screen readers. We use these standards to train volunteers. As mentioned previously, the platform allows administrators to review transcriptionists work as they proceed.

Encouraging your transcriptionists is vital to the success of a project like this. Even if they have the delight of transcribing hilarious letters from Mark Twain, it's really important to remember that someone who is getting up at 2 o'clock in the morning to do this as their gift to the world needs to be thanked. And we do appreciate it, so much. If you would like to be a part of this process, and join our wonderful transcription team, please contact me at hselsdon@afb.net.

Will you be sharing the results of your work, so that we can all benefit from your accessibility and usability findings, and improvements to the user interface?

Yes! We are delighted at this positive response to archive accessibility. We are still testing and refining the user interface as we add functionality. We look forward to sharing all of our recommendations, resources, and insights with the official launch of the Helen Keller digital archive.

I didn't know the American Foundation for the Blind had Helen Keller's Archive—what other archival materials do you have?

We have many seminal collections, not least of which is AFB's own archive. 550 record storage boxes that span from 1915 to the present describe the history of the burgeoning blindness field, blindness advocacy in the United States, and around the world. Materials also include the origins of assistive technology in the US, the standardization of English braille, the creation of agencies advocating for people with vision loss, as well as work surrounding education, rehabilitation and public policy.

AFB's M.C. Migel Rare Book collection contains over 700 volumes on non-medical aspects of blindness, spanning from 1617 to the 1960s. We also have the Talking Book Archive, which charts the history of audio recording pioneered in the 1930s by AFB. Fabulous oral histories recorded in the 1980s, as well as manuscript collections created by leading figures in the blindness field—such as Berthold Lowenfeld, Natalie Carter Barraga, Ray Kurzweil, and Josephine L. Taylor—add to AFB's wonderfully rich collections.

How would a person who is deafblind access the transcripts?

Screen readers are software programs that allow people who are deafblind to read the text that is displayed on the computer screen in braille. Refreshable braille displays provide access to information on a computer screen by electronically raising and lowering different combinations of pins in braille cells. A braille display can show up to 80 characters from the screen and is refreshable—that is, it changes continuously as the user moves the cursor around on the screen. The braille display sits on the user's desk, often underneath the computer keyboard. The careful transcription of all materials in the Helen Keller Archive make these primary sources accessible to all.

One quick question: how awesome is this project? [I swear we didn't plant this guy!]

Thank you! We think so, too, and are excited to carry on. We are so grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities for their support, as well as the many other individual, private, and corporate donors who have contributed to this labor of love!