Yesterday, the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) was proud to announce that we will be partnering with the American Printing House for the Blind (APH) to expand public access to the Helen Keller Archival Collection and the archives of AFB. AFB is loaning its historic collections to the APH Museum, making Louisville, Kentucky, an important center for the study of the history of blindness and disabilities in the United States.

Thanks to generous support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, American Express, and other funders, AFB will continue to maintain and enhance the digital Helen Keller Archive, www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive.

We are so excited about the opportunities this presents for even more people to experience these wonderful collections firsthand, and honored to share with you our archivist Helen Selsdon's remarks celebrating the new partnership.

It’s thrilling that both Helen Keller’s artifacts and AFB’s archive are coming to Louisville.

These two collections are critical sources of information about the history of blindness in the United States and advocacy for those with disabilities.

Having these materials at APH presents a golden opportunity to maximize the power of these collections to educate the public and future generations about Helen and disability history.

Helen is very dear to my heart. Allow me to tell you how amazing she was!

Most of us think we know Helen—that she was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama in 1880 and became deaf and blind at 19 months as a result of illness, and that when she was almost 7 years old, she learned to communicate using tactile finger spelling.

Sadly, for many, this is where the story ends. To think of Helen as a child at the water pump or a saintly old lady, is to come away with a very limited understanding of who she was and what she accomplished. And diminishes what we can learn from her life. Helen fought for those with vision loss, but she was also a fighter for freedom of speech and the right of every individual to live in dignity.

Keller was a staunch advocate of human rights. As a young, beautiful, and famous deafblind woman, she was embraced by the media and encouraged to write inspiring, uplifting narratives about overcoming difficulties. However, when in 1909 at the age of 29, she began to write about women’s rights, workers’ rights, pacifism, and her own socialist politics, she was increasingly criticized as unfit to join the discussion. Her gender and disability disbarred her from the conversation.

We know this did not stop her.

Helen went on to have a varied, fulfilling career. She appeared on the vaudeville stage in the 1910s and 20s, and on the world stage from the 1930s until the 1950s. She knew many luminaries from the late 19th century until the middle of the 20th and corresponded with figures such as Alexander Graham Bell, Mark Twain, Emma Goldman, Eleanor Roosevelt, Pearl S. Buck, Andrew Carnegie, John Steinbeck, and John F. Kennedy, to name but a few.

In 1924 she joined our organization, the American Foundation for the Blind, bringing her star power to the emerging blindness field. As AFB’s ambassador, she crisscrossed the nation from the twenties to the 1940s, demanding legislative change to improve the lives of people who are blind and visually impaired. Between 1931 and 1947 Keller appeared before 13 state legislatures, petitioning for the creation of State Commissions for the Blind and the construction of schools for those with vision loss.

Between 1942 and 1944, she supported Senator Robert Wagner’s efforts to secure funding for the rehabilitation, special vocational training, placement, and supervision of blind men and women, including those blinded in World War II.

Helen was outspoken and well informed. As early as 1933 she wrote a scathing letter to the Student Body of Germany, whom she excoriated for burning her book, and the work of other so-called degenerate writers. A fierce defender of the right to free speech, the letter condemned censorship and rising antisemitism in Germany.

Keller supported U.S. military action during the Second World War. Remaining stateside, she visited dozens of U.S. Army hospitals giving moral encouragement to wounded and blinded veterans.

And after the Second World War she took her work around the globe.

Her trips were three-month affairs, and her schedules were punishing. In a single day she would visit civic, government, and blindness organizations, as well as museums and cultural institutions. She would politely compliment her hosts on their work and then demand that their governments do more for its blind populations.

As an example of Helen’s impact: in 1952 she traveled to the Middle East, including Lebanon. In a report written later about her visit to Beirut, it was noted:

“…the Master of the Blind School, has found, as he goes about the city, very many people who still speak of that visit. It seems that they had not thought before of what could be done to help handicapped people to overcome their limitations. We believe that the establishment of a Lebanese society for the Blind and the interest of the Lebanese Government in such work has been largely due to Miss Keller’s visit.”

THINK ABOUT IT! When she made this trip in 1952, she was 72 years old, the Cold War was consuming the U.S., and American women were being relegated to the kitchen. And there was Helen, in her 70s, circumnavigating the globe, politically engaged, deaf, blind, and a woman.

I love to think of my Helen as a Trojan horse. This seemingly benign old lady packed a wallop and effected change, and what’s more, she did it with style.

Helen was a game changer. Not only did she improve the everyday lives of millions of people who are blind, she changed perceptions of blindness as well.

And incredibly, it’s all there in the Helen Keller Archive—a unique cultural repository.

Since 2015, AFB has been digitizing her collection, and I’m proud to say that over 185,000 digital images are now available worldwide. But what is truly special about this project, and why it’s become a pet project of our main funder, the National Endowment for the Humanities, is that it is fully accessible to people who are blind, deaf, hard of hearing, and deafblind, as well as sighted and hearing visitors. As far as we know, it’s the most accessible archival collection currently available and we believe that we have created a gold standard for other cultural institutions to follow. And it’s all available at www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive.

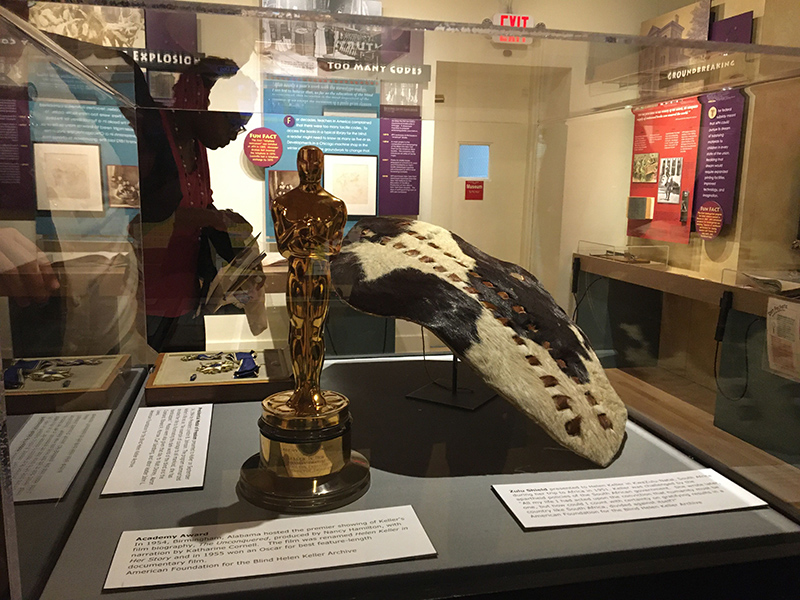

But. At the end of the day, there’s nothing quite like the original item to bring history home. There’s nothing as delicious and juicy as the real, tangible object. The Zulu shield, the letters from Mark Twain and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the embossed glass vase from the women of Sao Paulo, and the Academy Award—these tangible objects delight audiences and make it a little easier to take part in the historical debate, and they go a long way towards engaging young audiences.

I am excited at the prospect of APH hosting these artifacts in their museum. Not only is this an opportunity to educate the public about Helen and disability history, it’s a chance to illustrate the importance of civic engagement, the value of service and kindness, and the power of diverse perspectives.

Many children visit APH, and I’m delighted that kids who visit who have disabilities will be able to see themselves in history, and those kids who can see and hear will learn about the achievements of those with disabilities.

This is long overdue, and together APH and AFB will bring disability history into the mainstream where it belongs.