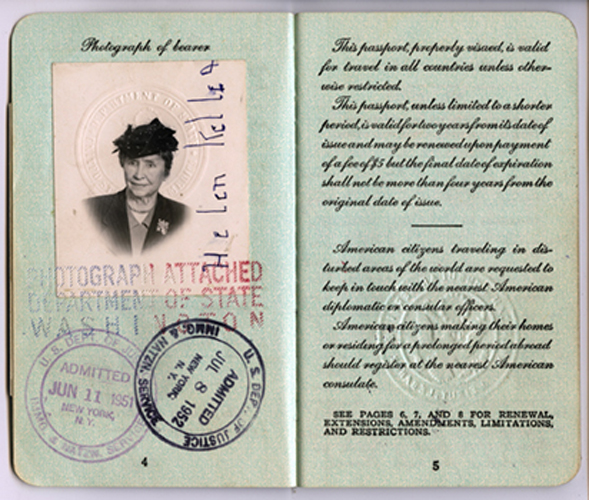

Image: Inside pages from Helen Keller's passport issued December 1950, including headshot of Keller wearing a hat.

This week on Inside the Helen Keller Digitization Project, University of California, Berkeley, English professor and author of Blind Rage: Letters to Helen Keller Georgina Kleege, describes her excitement at the prospect of gaining access to previously unavailable materials including transcripts of Keller's performances on the Vaudeville circuit, travel itineraries from her work around the globe and audio recordings of Keller's voice, newly digitized and embedded in Kleege's blog post below. Read, listen and enjoy!

Recently, I asked my students to survey their friends to find out what they knew about Helen Keller. The majority of them had heard the name, and most knew that she was deaf-blind, or at least that she was blind. Many were familiar with some version of The Miracle Worker, and so knew the story of how she came to learn language from her teacher, Anne Sullivan. But few seem to know much about Keller's life as an adult, her career as a writer, lecturer, performer, and fundraiser for the AFB. And sadly, my students' survey revealed a good deal of misinformation; for example, several respondents thought that Helen Keller invented braille.

This is why I am so excited that the Helen Keller Archive is being digitized. It will give everyone easy access to materials that will convey the diverse range of activities and accomplishments over the course of her long life. In addition to her published writing and her vast private correspondence, the archive includes a wealth of other information that may surprise people today. For example, few people today remember that Keller performed in Vaudeville for a couple of seasons. The archive includes scripts of these performances where Keller and Sullivan described Keller's education and demonstrated how she communicated using the manual alphabet. The archive also includes some itineraries of some of Keller's national and international trips. These convey a sense of Keller's worldwide celebrity as well as her boundless energy. Many of her trips took her around the world, and she was in such demand that she frequently made multiple appearances in a single day.

The items that I am most excited to access from the archive are the audio recordings of Keller's voice. For example, there is a recording of Helen Keller reciting the Twenty-Third Psalm. Although finger-spelling was Keller's primary mode of communication, she did learn to speak orally. She felt it was an important way to reach a wider audience. She regretted that she did not receive speech training earlier in her life because she knew that her speech was not readily comprehensible. Audio recordings reveal that while Keller's enunciation is not always clear, she made the most of nonverbal elements—intonation and pitch—to make herself understandable. In my book Blind Rage, I recall hearing Helen Keller on the radio when I was a child. At the time, her atypical voice seemed at odds with what I knew about Keller from school, and I found it uncanny, even disturbing. Now, having researched Keller's life and written a book about her, I have a different understanding of her speech. As a blind person, people's voices are fundamental to my feelings about them. So it will be great to have this digital connection to someone I never met personally, but nevertheless played a big role in my life.

Sound files digitized with the support of Mills NSF Award No. 135429.