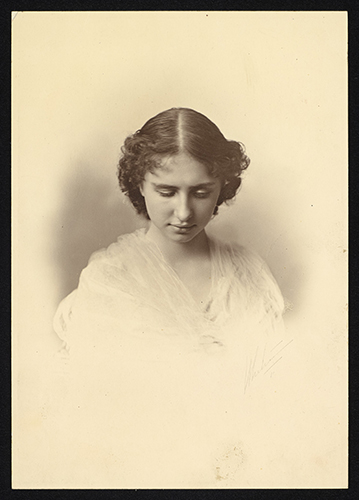

Helen Keller circa 1893.

As an archivist, at the Perkins School for the Blind Archives, I often spend a lot of time tracking down information. While I relish a mystery and the process of its’ unraveling, these searches rarely come with a desirable deadline or at an opportune moment. Last summer, I was tasked with trying to track down materials that had been accessed before the Perkins School for the Blind had an archives program, archivist, or finding aids (pre-2011). The task was daunting, but almost all of it turned up in processed collections. I was lucky.

One letter however— part of the Helen Keller Archive— proved frustratingly lost. The unexpected journey this search took me on, ended up being an excellent reminder about the value of primary resources and the role digitization can play in democratizing access to it.

The letter I sought, written in September 1906, was described as a copy written by Helen Keller to Frank Sanborn. In it, Helen states that a friend told her that Michael Anagnos, the director of the Perkins School for the Blind, had called Helen a "living lie." The letter sent to Sanborn after the death of Anagnos outlined the wrongs she felt were done to her and Anne Sullivan by the director fourteen years earlier, when twelve year old Helen was accused of plagiarism. The episode became known as the Frost King incident. This "living lie" quote is popular and easily found online without citation. When I went into the library stacks, I found the letter mentioned in two acclaimed biographies of Keller. One gave attribution to the American Foundation for the Blind and one to the Perkins School for the Blind.

The next logical step was contacting AFB Archivist Helen Selsdon. Selsdon was able to confirm that they had the letter. Luckily it was one of the documents that had been both digitized and had metadata attached, making it available on the Helen Keller Archive. I now had access to an image and transcription of the typewritten letter that started with "Copy of Helen’s letter to Frank. B. Sanborn." Page two revealed that often quoted line, a living lie."

Being able to access the digitized letter online gave me an answer I could point to, and reminded me of just how valuable access to primary sources is. A select few researchers can physically access repositories. Whether the encumbrance is distance, time, limited finances, or any number of other reasons, digitization is our best resource in providing more equitable access to collections. Institutions with related collections, like ours, can provide a more comprehensive picture of a topic, and can do so to a much more diverse group of people. Digitization also means more researchers aren’t dependent on secondary resources or a single quote. I can’t wait for the day when citations are no longer a static guide but linked to a digital surrogate of the whole resource.

Technology continues to bring us closer to this goal, but the Helen Keller Archive stands as a remarkable example of what equitable access should be. It is not merely a digitized letter written by Helen Keller, but a digitized copy that Helen herself would have access to if she were alive. In a rush to get historical material online, accessibility considerations have been ignored or sidelined far too long. The digital access provided by AFB stands as an essential example that other cultural institutions can and must learn from to make historical collections genuinely available to all.

Note: Jen Hale is the Archivist at the Perkins School for the Blind.