This article reviews four stand-alone Digital Talking Book (DAISY book) players available in the United States--the Victor Reader Classic Plus and Victor Reader Vibe from VisuAide, the Telex Scholar, and Plextor's Plextalk PTR1 player/recorder. These players represent one of the two principal types of players for reading DAISY books; the other type is software players that are used on computers. The stand-alone machines are the easiest to learn to use, and they can be small and portable. They are also the most affordable players for people who do not own a computer. For more information on DAISY books, what they are, and where to get them, read "A Rosy Future for Daisy Books" in this issue.

Our tests were conducted using DAISY books from Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic (RFB&D) and other sources, as well as MP3 files and commercial music CDs that can also be played on these players.

The DAISY format is still new and unfamiliar to most potential users in the United States. Each book has to be coded by the producer, just as web-site designers code each web page. It is not possible to know how much coding is done in a book until you listen to it. As a result, if a player did not perform a function, such as going to a designated page of a book, we had to try the task using another player to determine if there was a mechanical problem or if the function was just not available in that book.

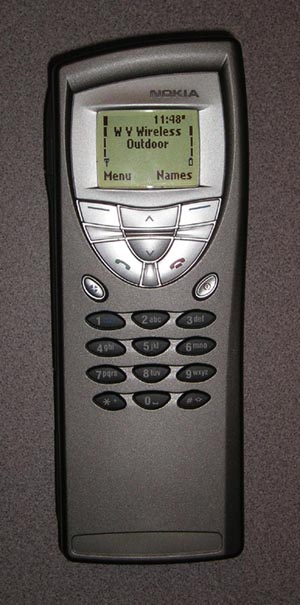

Victor Reader Classic Plus

Physical Description

The Victor Reader Classic Plus measures 9.3 inches by 8.2 inches by 2.1 inches and weighs 2.42 pounds. It is ergonomically designed; the top surface slopes upward from the front to the back. The built-in speaker is at the top left of the unit. Below the speaker is a carrying handle. On the right side of the unit, from the back to the front, are the AC (alternating current) adapter, a line jack, a remote jack, and an earphone jack.

Caption: The Victor Reader Classic Plus.

The Classic Plus has 25 keys. To the right of the speaker, across the top of the Classic Plus, are three vertical sets of two keys each. From left to right, these keys control the tone, volume, and speed of the audio. Below these keys is a 12-key telephone-style keypad. The 5 key has a raised dot in the middle; the 4 and 6 keys have raised arrows pointing left and right, respectively; and the 2 and 8 keys have less-pronounced arrows pointing up and down, respectively.

Below the number keypad, from left to right, are the Rewind, Play/Stop, and Fast Forward keys. The Play/Stop key is square, and the Rewind and Fast Forward keys are shaped like arrows. The key that ejects CDs from the Classic Plus is to the right of the Fast Forward key. The Power On-Off key is above the Eject key.

Documentation

The Classic Plus's manual and Quick Reference guide are provided on a DAISY CD. A print Quick Reference is also included. The Quick Reference does a good job of orienting the user to the Classic Plus's keys and basic functions. The manual is detailed and thorough. However, accessible documentation is provided only in DAISY format, so you must figure out how to play a CD on an unfamiliar machine to know how to operate that machine. We recommend that a Quick Reference guide be included on audiocassette tape, the format used by the most people.

Ease of Use

The Classic Plus is a full-featured Digital Talking Book player. It is ergonomically designed, and its keys are easy to find tactilely. It has a Key Describer mode that functions when the unit is turned on and there is no CD in the drive. Under these conditions, the Classic Plus will announce the function of any key that you press.

Most of the keys on the Classic Plus's numeric keypad have an additional function. The 2 and 8 keys are the Scroll Up and Scroll Down keys. You use them to change the navigation setting in a book--from phrase to page and so forth. The 4 and 6 keys navigate backward and forward, respectively, according to the navigation level you set with the 2 and 8 keys.

The 1 key is the Bookshelf key. It takes you to a list of all the books on the current CD. The 3 key accesses the History list, which allows you to return to places you have been reading in the book. For example, if you move from a subheading in Chapter 5 to the beginning of Chapter 7, you can then go back to the same subheading by accessing the History list and pressing the Move Back key.

The 5 (Where Am I?) key announces the current page and level of navigation. The 9 key is the Sleep key. It lets you set a period, up to 60 minutes in 15-minute increments, after which the unit will shut off.

The 0 key is the Information key. It tells you the total time elapsed and the total time remaining in the book you are reading. To the left of the 0 key is the Cancel key; to the right of the 0 key is the Confirm key.

When you insert a DAISY CD, the Classic Plus takes 10 seconds to access the CD and announce the book title. It takes 7 seconds to access a commercial music CD. Moving to the next track on an audio CD or going to a specified track using the Go To key takes 2 seconds.

When you insert a music CD, the Classic Plus announces "Track 1." You then hit the Play button to play the CD. The Classic Plus allows you to adjust the volume, tone, and speed of the music being played. When you press the Where Am I? key, the Classic Plus announces the current track number and time elapsed for the song. The Bookshelf key puts you in the track list and announces the track number and its total time--for example, "Track 2 total time 5 minutes, 18 seconds."

The Classic Plus is well designed. Its keys are easy to learn and use. The Classic Plus functioned well during our tests.

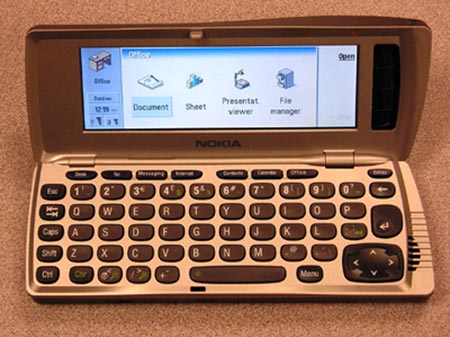

Telex Scholar

Physical Description

The Scholar measures 6 inches by 5.5 inches by 1 inch. It is a clamshell-style device with a distinctive, ergonomic shape. The case is gray. The AC adapter and a data port are on the back of the unit, near the left edge. On the right side of the Scholar are the earphone jack and the switch to lock the keyboard. You move this switch toward the back of the unit to unlock the player. On the front of the Scholar is a latch that locks the top in place. The Scholar has no built-in speaker, so you must listen using headphones or attach an external speaker.

Caption: The Telex Scholar.

The Scholar has 19 keys on its top surface. At the top are 5 blue buttons. The 2 buttons at the left edge control the volume of the audio, and the 2 buttons at the right edge control the speed. The longer button in the middle is the undo-redo button.

Below these five buttons is a telephone-style numeric keypad. The 5 key, which performs multiple functions, is a round red button half an inch in diameter. The 2, 4, 6, and 8 keys are arrow-shaped blue keys that are also half an inch long. The other numeric keys are small silver buttons.

There are two more small silver buttons at either end of the 4, 5, 6 key row of the numeric keypad. The key to the left of the 4 key is the Page key; the key to the right of the 6 key is the Bookmark key.

Documentation

The Scholar's manual and Quick Reference guide are provided on a DAISY CD. The description of the player's buttons was somewhat confusing. For example, the 2 key is referred to as "The arrow on top of the Play button (the 5 key)." The description "If you pick up the player with two hands, your left and right thumbs should find two buttons near the edge of the player" is not specific enough. In general, the keys are described not in physical sequence, but by function. So, we were constantly searching for the key that was being described.

Ease of Use

The Scholar is not easy to use. The 5 key, which also serves as the Play-Stop, Power On-Off, and Menu key, is an overworked button. We were sometimes confused about which of this key's functions we had selected, especially when the Scholar was slow to respond. The fact that the arrow keys, 2, 4, 6, and 8, are so much larger than the other numeric keys left us searching around for the other keys when we needed them. People with low vision will appreciate the color-coded keys, but anyone with dexterity problems may have trouble finding the smaller keys. People who are blind are familiar with a telephone keypad on which the keys are all the same size. Adding tactile markings on the 5 key and possibly on the arrow keys would be sufficient.

Every time you turn the Scholar on, you have to listen to it slowly speak its serial number, tell you it is accessing the disk, and then hear numerous tones that sound like steel drumbeats until it recognizes the current CD. The volume of the unit's command voice is often louder than the volume you have set for the audio of the book, which can be startling.

When you insert a DAISY CD, the Scholar takes an average of 29 seconds to access the CD and announce the book title. We used an average of the access times for 5 CDs, since the times varied widely, from a high of 54 seconds to a low of 13 seconds. The Scholar takes 6 seconds to access a commercial music CD. Moving to the next track on a music CD takes 2 seconds. The Scholar tells you that a CD contains MP3 files by playing three musical tones and plays two different tones to identify a commercial music CD. While you are playing a music CD, you cannot adjust the speed of the music, and functions, such as Go To or bookmarks, are not available.

The Scholar was confusing and frustrating to use. Its use of sound effects as indicators of problems, such as an invalid entry on the keypad, were not helpful. We were left trying to remember what each buzz, click, or drumbeat meant and what we should do next. To our great surprise, we managed to "crash" the Scholar several times, as you would a Windows computer. One way was to hold down the Play button in an attempt to turn the Scholar off. After a few seconds, we were shocked to hear the Windows "Tada" sound effect as the Scholar "rebooted."

Victor Reader Vibe

Physical Description

The Vibe measures 5.5 inches by 5.5 inches by 1 inch. It is a clamshell-style device with 11 buttons on its top surface arranged in the shape of an old rotary telephone dial. The number 1 button is at the top right, and the numbers ascend moving clockwise. The buttons have multiple functions. The Vibe features visual icons and embossed tactile markings that group the buttons together by function. For example, the Fast Forward, Play-Stop, and Rewind buttons are grouped together by raised tactile lines.

Caption: Victor Reader Vibe.

You turn the Vibe on by pressing Button 1 and turn it off by pressing and holding down Button 2. Buttons 1 and 2 also increase and decrease the volume and speed of the audio. Button 3 toggles between the Speed and Volume modes. Buttons 4, 5, and 6 are Fast Forward, Play-Stop, and Rewind, respectively. Button 7 is the Go to Page button, and Button 8 is for placing bookmarks in the text. Button 9 is the Menu button. Button 0 and the pound button move to the previous and next elements, respectively. In a DAISY book, an element can be a chapter, page, or paragraph; on a music CD, an element is a song.

On the right side of the Vibe, moving from the back toward the front of the unit, are the AC adapter, line-out jack, a port that is currently unused, the earphone jack, and the keyboard lock switch--sliding it toward the front unlocks the keys. To insert a CD, you move the only button on the front of the unit to the right, and the lid pops open. When you close the lid, it clicks shut. The Vibe has no built-in speaker, so you must listen using headphones or attach an external speaker.

The Vibe runs on two AA batteries. Rechargeable batteries are included.

Documentation

The Vibe's manual and Quick Reference guide are provided in print and on CD. The description of the unit in the manual is clear. The manual does a good job of describing the Vibe's features and functions.

Ease of Use

The Vibe is relatively easy to use. However, some people may find the rotary phone-style key layout and the lack of tactile markings on the keys confusing. The tactile markings that group the keys together by function help, but checking for them, rather than instantly knowing that you are touching the right key, may slow some people down.

When you insert a DAISY CD, the Vibe takes an average of 25 seconds to access the CD and announce the book title. We used an average of the access times for 5 CDs. These times varied from a high of 30 seconds to a low of 19 seconds. The Vibe takes 19 seconds to access a commercial music CD and 2 seconds to move to the next track on an audio CD.

When you insert a CD, the Vibe automatically accesses the disk. If it is a DAISY CD, the Vibe announces "Welcome to Victor," followed by the name of the book. You then press the Play button to start reading the book. When you put an MP3 or commercial music CD into the Vibe, the player accesses the disk and begins playing the music. While playing a music CD, you cannot adjust the speed of the music. Functions, such as Go To or bookmarks, are not available.

The Vibe performed reliably during our tests. The digitized voice that confirms commands was clear and at a consistent volume level. A problem occurred when we inserted a DAISY book that used .wav files instead of MP3 files. Although the DAISY specifications allow .wav files, the Vibe does not play them.

Plextalk PTR1

Physical Description

The Plextalk PTR1 measures 7 inches by 6 inches by 1 3/8 inches and weighs 1.9 pounds. Its design, which will be familiar to anyone who is acquainted with Plextor's CD- ROM burners, is reminiscent of a hardbound book with a curved spine to the left, edges that stick out a little as a book's cover sticks out beyond the pages, and a ragged right edge suggesting well-thumbed content. It is also much more than just a stand-alone player. It can record and play DAISY titles, MP3, and .wav audio files and store them on a PCMCIA Type 2 card. You can use the PTR1 to create and edit your own DAISY book and burn a CD-ROM; it also provides built-in DAISY editing features. And, if you would rather edit on your computer, the PTR1 comes with Windows software to do just that.

Caption: The Plextalk PTR1.

The PTR1's "back cover" has four small rubber feet, so it is easy to tell that the PTRI is supposed to lie on its back cover. There are controls or input/output ports on all remaining surfaces.Continuing with the metaphor of a hardbound book, the spine contains one push-pull switch to turn the unit on and off. Push up to power the PTR1 on, and a distinctive audio logo is played immediately to confirm that the unit is powering up. Various bits of status information are spoken as the unit boots, telling you whether you are accessing a disk or the PC card and what book you have inserted or that you have inserted an audio disk, as the case may be. Pull down on the same switch, and the PTR1's Guide Voice immediately announces "Shutdown." There is even a brief audio earcon, an audible icon; that is, a sound used to represent a specific event to let you know that shutdown has concluded.

Also on the spine are three 1/8-inch jacks--line-in, external microphone in, and headphone out. Inserting a cable into any of them causes the Guide Voice to announce what connection you have made, so it is easy to know when you have plugged into the wrong connector.

A power connector and a USB connector are the only features on the top edge--the edge that would be the top of the printed pages if this were an actual book. The PCMCIA slot for additional memory cards and other add-ons is the only port on the right-hand edge. We had no problem using even a 5-gigabyte hard disk in this slot. The PTR1 comes with a rechargeable battery.

Most of the PTR1's controls are simply laid out on the front cover. The speaker and microphone are positioned at the top edge. A 12-key numeric keypad is positioned to the right side of the front cover, with Reverse, Stop-Start, and Forward buttons below it. The Stop-Start button is square, and the Reverse and Forward buttons are triangular arrows pointing left and right, respectively.

A column of five special-function keys is positioned along the left edge. Each of these five keys is larger than the one above it. The first four of these keys are diamond shaped, and the fifth, the Record-Pause key, is round. The topmost button lets you set the sleep timer or learn the current time and date. You enter the sleep time by typing numbers and then pressing pound (called Enter) on the numeric keypad. You can set the PTR1 to turn itself off as much as 999 minutes in the future--well beyond anything one may reasonably need, it seems to us. To hear the time and date, simply hold this button down.

The second key down is the Heading key. With a short press, you are placed in the "Go to Heading" function. Enter a number within the range of available headings in the current book via the numeric keypad to go directly to it. You cannot navigate effectively this way in an audio-only DAISY book, because you can't search for the text of a particular heading. To hear the current heading and how many total headings are encoded in the current book, simply hold this key down. The third key is the Page button. Press it briefly to enter the "Go to Page" feature and enter the page you want via the numeric keypad; hold it down to learn the current page and the total number of pages in the current book.

The fourth key is the Bookmark key. This key has four positions. Press this key once to enter the "Go to Bookmark" feature. As before, you can enter a bookmark number via the numeric keypad. But, if you press the Bookmark key a second time, you enter the "Set Bookmark" feature. Type a number on the numeric keypad to associate that number with the current position in the book. Press the Bookmark key a third time, and you access the "Set Voice Bookmark" feature. As before, you still type a number on the numeric keypad to identify the current position by bookmark number. But then you are instructed by the Guide Voice to hold down the Record key while you say whatever you want to record. Your recording is then associated with that bookmark, so that you hear your recording when you go to that bookmark. It is a clever way to store notes about what you are reading, and it is the only feature like it that we have found so far on stand-alone DAISY players. Finally, a fourth press of the Bookmark key takes you to the "Remove Bookmark" feature. Holding the Bookmark key down provides information about the current bookmark and the total number of bookmarks and total seconds of recorded voice bookmarks.

As we noted previously, the fifth key in this column is the Record-Pause key that you can use to record an entire lecture. If you do so, you can even put DAISY markers in your recording that you can navigate to when you listen to your recording.

The numeric keypad is used in a straightforward manner. There is a nib at the center of the 5 key, and there are left and right arrows, respectively, on the 4 and 6 keys for navigating to the previous and next element, according to the navigation level that you set with the 2 and 8 keys, which also have arrows on them pointing up and down, respectively.

The star key is Cancel on the PTR1, and the pound key is Enter. The 5 key exposes an extensive menu of settings and additional features that include recording settings; data about your unit, such as the serial number; all the DAISY editing functions that you need to edit your recordings; a calculator; a note recorder; and much more. These menus are navigated just as you navigate a DAISY book, using the 4 and 6 keys to move backward and forward through the various choices. Pressing 8 exposes any submenus that may be present for any given menu item or acts as Enter on that item. Pressing 2 eventually takes you out of the menus.

The remaining surface that faces you contains the opening to the motorized disk tray. Insert a CD a little way, and the motor will pull the disk into the PTR1 and start playing it. Below the disk opening are five buttons. The three to the left have a ridge and different functions that you toggle by pressing them. The fourth button is a simple two-position switch that toggles Keylock on and off. The last button at the far right is the CD Eject button.

Returning to the three controls to the left of this edge, they are, in order, Record and Monitor level, Speed-Tone, and Volume. Toggling the first allows you to set either the recording or the monitor level by then pushing to the right or left with the same button. Toggling the second allows you to set either speed or tone higher by moving the button to the right or lower by moving it to the left. Similarly, the third control allows you to set the volume higher or lower by pushing the button to the right or left. Pushing it in allows you to toggle between Playback and Guide Voice volume settings.

Documentation

Documentation for the PTR1 is provided on a DAISY CD-ROM disk. We were particularly disappointed, however, by the poor quality of the writing in this manual. It was clearly not written by a native English speaker and hence was difficult to understand. Fortunately, a new, professionally written manual for the PTR1 is being prepared by the Royal National Institute of the Blind (RNIB), which should make this feature-rich device far easier to learn and use. Plextor says that this manual will be available in the first quarter of 2004.

Ease of Use

The basic features of a DAISY book are easily accessed by the PTR1's well-organized keys. We found loading content to be straightforward, taking on average about 12 seconds, with a minimum of about 10 seconds and a maximum of 17 seconds to load DAISY and/or audio CD media. Moving forward or backward using the 4 or 6 keys took, on average, 1.5 to 2 seconds. Unfortunately, even this short amount of time was sufficient to trigger the "I'm working" audio signal. It is certainly handy to have an audio indication that the unit is doing an activity that is taking some time. However, we would like the threshold set significantly higher, especially since the audio clip that the PTR1 uses for this function is musically rich, incorporating the interval of a major seventh. Something less obtrusive than this startling interval, set to play at a higher threshold, would be better.

We also wish it were possible to set the speed of the Guide Voice independently. We got accustomed to the guidance provided by the Guide Voice and found it useful to push its speed high. But, especially with the content we recorded, but also with the content on DAISY books we obtained from the library, we frequently wanted playback at a different, usually lower, speed. Frankly, we would be happy to set both guide and content volume the same and have two speed controls--one for Guide speed and the second for Content Playback--but it is not possible to do so.

We also wish we could assign keys, perhaps on the numeric keypad, as shortcuts to our choice among the numerous menus controlled by the 5 key. Many of the functions that are available through these menus need to be used repeatedly to perform a task like editing out unwanted audio from a recording or assigning different level markings to the final edited recording. It would be nice to be able to return to that menu swiftly, rather than by navigating each and every time. Why not make it possible to insert bookmarks in these menus just as you can bookmark random points in content?

There is certainly much more we could say about this unit. With its many features, it could fill an article on its own. Generally, we like using the PTR1.

The Bottom Line

Since the previous evaluation of DAISY book players ("Who Are the Players: Reviews of Hardware and Software Digital Talking Book Players," May 2001 issue of AccessWorld smaller, more portable, players have come on the market. The four machines reviewed here represent three categories. The Vibe and the Scholar are small, lightweight portable machines that are ideal for traveling. They have no built-in speakers and offer a limited number of features. The Classic Plus is a full-featured digital Talking Book player that offers the full range of features that are available in this exciting new medium. The PTR1 includes everything that is found in the Classic Plus, along with the ability to record and edit in DAISY format. These products' prices reflect the differences in their features.

For DAISY to become a widely used format, players that are much easier to use must be developed. The average Talking Book reader will not use some of the features discussed here. Simpler machines with friendly documentation in familiar formats will go a long way toward making the DAISY format bloom.

Manufacturers' Comments

VisuAide

"VisuAide is known as the leading maker of digital Talking Book players, with over 40,000 Victor Reader units sold around the world, and has the largest DAISY product line. Victor Reader players are used by subscribers of leading libraries for the blind, including RFB&D in the United States and the Royal National Institute of the Blind (RNIB) in England. The Victor Reader Vibe and Classic Plus models are players with advanced functionality that can read complexly structured works, such as textbooks and reference works. The Victor Reader line also includes a simple-navigation model with basic functionality, the Victor Reader Classic, and a software application for reading DAISY books on PC, Victor Reader Soft. A member of the DAISY consortium defining international digital Talking Book standards, VisuAide actively participated in the development of the new DAISY and NISO Z39.86 Digital Talking Book standards."

Telex

"Telex introduced the Scholar Talking Book player as the first fully portable DAISY player in the world. We have designed a product that brings consumer technology to the DAISY market at pricing that is significantly lower than the traditional DAISY players. The Scholar offers the opportunity to take reading anywhere even while enjoying other activities. With the lower price and portable size, the Scholar also offers all the advanced navigation features of the higher-priced players.

"The Scholar allows users to access pages by typing the page number on the numeric keypad that is the same layout as a telephone. Users have access in seconds to pages that took many aggravating minutes to find in cassette books. The Scholar is also able to play many hours on four AA batteries and has an extremely rugged design.

"Telex will be offering DAISY 3.0 and NISO Z39-86 playback capabilities in March 2004 that will be available to download into existing players. Firmware upgrades are available at <www.telex.com/duplication/updates>."

****

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

****

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Product Information

Product: Victor Reader Classic Plus

Manufacturer: VisuAide; 841, Jean-Paul-Vincent, Longueuil, Quebec, Canada J4G 1R3; phone: 888-723-7273 or 819-471-4818; e-mail: <info@visuaide.com>; web site: <http://www.visuaide.com>. Price: $375.

Product: Telex Scholar

Manufacturer: Telex Communications; 12000 Portland Avenue South, Burnsville, MN 55337; phone: 952-736-4233; e-mail: <info@telex.com>; web site: <http://www.rfbd.org>. U.S. distributor: Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic; 20 Roszel Road, Princeton, NJ 08540; phone: 866-732-3585; web site: <http://www.rfbd.org>. Price: $249.

Product: Victor Reader Vibe

Manufacturer: VisuAide; 841, Jean-Paul-Vincent, Longueuil, Quebec, Canada J4G 1R3; phone: 888-723-7273 or 819-471-4818; e-mail: <info@visuaide.com>; web site: <http://www.visuaide.com>. Price: $219.

Product: Plextalk PTR1

Manufacturer: Plextor Corp.; 48383 Fremont Boulevard, Suite 120, Fremont, CA 94538; phone: 510-440-2000; e-mail: <info@plextalk.com>; web site: <http://www.plextalk.com>. U.S. distributor: Innovative Rehabilitation Technology; 13465 Colfax Highway, Grass Valley, CA 95945; phone: 800-322-4784; e-mail: <info@irti.net>; web site: <http://www.irti.net>. Price: $995.