Did you attend the conference of the Assistive Technology Industry Association in Orlando, the Technology and Persons with Disabilities conference in Los Angeles, or AFB's Josephine L. Taylor conference in San Francisco this year? Are you planning to attend the national conferences of the National Federation of the Blind or American Council of the Blind this month? Perhaps you are planning to visit your grandchildren in Louisville or your grandparents in Lancaster. Whatever your travel plans, they may well include a long, boring airplane flight.

To make long flights more enjoyable, several major commercial airlines offer in-flight entertainment and information systems to their passengers. Many of these systems are operated via a touch screen that is located on the back of the seat in front of you. While the passenger sitting to your left may be giggling while watching a movie she selected from the touch screen interface, the man to your right may be high-fiving himself because he is winning the trivia game that he is playing with other passengers on the flight. Although these options may be great for many passengers, they are inaccessible to those who are blind and to most who have low vision, as well as to people with other disabilities—such as people who are deaf, hard of hearing, have motor impairments, and who struggle with literacy.

In addition to movies and games, airlines are increasingly offering passengers Internet connectivity, which can turn their airline seats into extensions of their workplaces or home offices. These in-flight entertainment and information systems often offer other features, such as the ability to select from genres of music and artists to listen to and up-to-date flight information. The flight information can be anything from the number of miles you have traveled to the time remaining in the flight and the altitude at which you are flying. These systems may also provide connecting information on gates for connecting flights, tell you if your connecting flight is on time or delayed, or let you know where your baggage claim is located. All this can be yours if you can read the text on the screen and use the touch screen interface.

If you are unable to use the touch screen interface, it can be extremely frustrating knowing that all these features to make your flight more enjoyable are literally at your fingertips but, in essence, are far out of reach. There may be some good news on the horizon, though. In 2005, the WGBH National Center for Accessible Media (NCAM) was awarded a three-year grant (2005-08) to research and develop solutions to make airline entertainment, communications, and information accessible to passengers with sensory disabilities. The resulting recommendations will cover the integration of captioning for video, video description for video and visual images, and audible navigation of the system's menus and accessible interface design.

In-flight entertainment (IFE) systems represent yet another area in which the pervasiveness of media technologies in every aspect of our lives is needlessly placing people with disabilities at a disadvantage. Given the role that communication technologies and news media play during emergencies, the need for equal access to information via in-flight entertainment and news systems is critical to the safety of passengers with disabilities.

I recently had the opportunity to try out the prototype in-flight entertainment and information system, as well as to watch other people who are visually impaired test it. As with all new technologies, refinements are still needed, but the people I saw using the system were hopeful and excited about its potential and the possibility of having access to flight entertainment and information systems as they travel.

The Prototype System

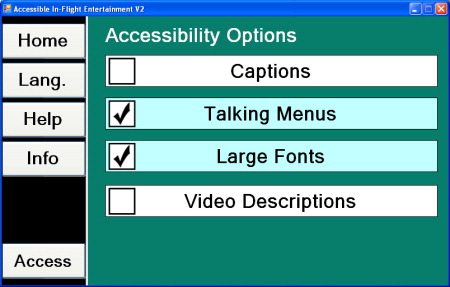

NCAM's prototype was designed on an IFE system offered by Panasonic Avionics Corporation and demonstrates an accessible interface, user-selectable captions, selectable fonts, video description, and talking menus. With the addition of a handheld EZ-Access style remote control (http://trace.wisc.edu/projects/ez) to a touch screen interface, people with visual impairments can have access to many of the features just mentioned. The tactile keypad remote control works in conjunction with the system's on-screen Large Font mode, Spoken Menus mode, or Spoken Menus with Large Fonts mode. You press the Up and Down arrow keys on the remote to navigate through the menus, which are read aloud. Then you press the circular key, located on the lower right side of the remote, to select the desired menu item. There are also a Back button and a Help button to assist you in navigating the system.

Caption: The Accessibility Options screen displaying in Large Fonts mode with Large Fonts and Talking Menus options both checked.

Larry Goldberg, director of NCAM, noted that some airlines are beginning to explore IFE systems that use a browser-based interface and are designed to work with personal devices, such as laptops, PDAs (personal digital assistants), and Smartphones, for Internet and e-mail access. If properly implemented, these new interface designs may serve consumers who require keyboard access for alternate navigation.

NCAM is working with the World Airline Entertainment Association (WAEA), a membership organization that represents 100 airlines and more than 250 airline suppliers and related companies, to inform members about accessibility needs, develop amendments to industry specifications, and promote the implementation of potential solutions within IFE. After a number of years soliciting comments about access issues related to travel, the U.S. Department of Transportation recently issued a Notice of Final Rulemaking that includes some requirements that are related to captioning but does not address the accessible navigation of IFE systems. Working within the WAEA and with the National Center on Accessible Transportation at Oregon State University, NCAM has as its goal to show technology and policy developers that accessibility is possible within the next generation of IFE systems if the interface is properly designed and captions and descriptions are included in the content-distribution chain.

"Many of the movies shown on airlines have already been captioned and/or described for showing in those theaters that have installed access technologies (such as WGBH's MoPix system)," Goldberg noted. "The challenge is similar to some of the work we are doing on the web and with handheld devices. We find that companies are using content-management systems that have no provision for identifying or carrying captions or descriptions and customized media players that cannot play supplemental audio or text tracks. Through this grant, we are working with IFE suppliers to see how we can make it easier for their content-management systems to include caption and description files and with IFE system developers on the hardware and software interface."

This work is being funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, U.S. Department of Education, under Grant H133G050254. The user testing of the prototype will result in a report and recommendations for the airlines and their suppliers. When the report is complete, the idea of accessible entertainment and information systems will need to be sold to the commercial airlines, and the airlines will have to acquire the necessary equipment and software to ensure accessibility. We at AccessWorld will follow the development of this technology and let you know when more information is available about the accessible in-flight entertainment and information systems that NCAM is working to make a reality.

If you would like to comment on this article, e-mail us at accessworld@afb.net.