Whether you are particularly interested in technology or not, if you or someone you know is blind or has low vision, it is a safe bet that you have heard about the Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind (NFB) Reader (hereafter, the Reader). Officially released on July 1, 2006, this small device, which enables people who are blind to read print, was featured in numerous print and broadcast outlets, from the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times to Good Morning America and CNN. According to Fleishman-Hillard, the public relations firm that has gathered data on the product, by August 18, the Reader had been the subject of 175 articles, 904 broadcasts, and 54 online pieces around the world.

Certainly, other forms of blindness technology have captured the imagination of the mainstream media, including braille personal digital assistants (PDAs) and portable magnifiers, screen readers, and mobility devices. But the last time a product received such widespread attention may well have been when inventor Ray Kurzweil announced the Kurzweil Reading Machine. That machine was also featured on many popular morning and evening news broadcasts and enjoyed the distinction of being the only voice other than his own that was ever permitted to speak Walter Cronkite's sign-off message on his long-running CBS News program, saying, "And that's the way it was, January 13, 1976."

With his original invention, Kurzweil began a 30-plus-year relationship with people who are blind, seeing new generations of the concept evolve—from a tabletop stand-alone model to computer-based software that could produce text-to-speech from documents that were scanned with an attached desktop scanner. In 2001, when the NFB held its groundbreaking ceremonies for the Kenneth Jernigan Institute in Baltimore, Kurzweil made one of his legendary predictions: We could have a portable reading device, one that people who are blind could actually carry around with them, within four to five years. With that pronouncement, Kurzweil Technologies began a collaborative effort with the NFB to make the prediction a reality.

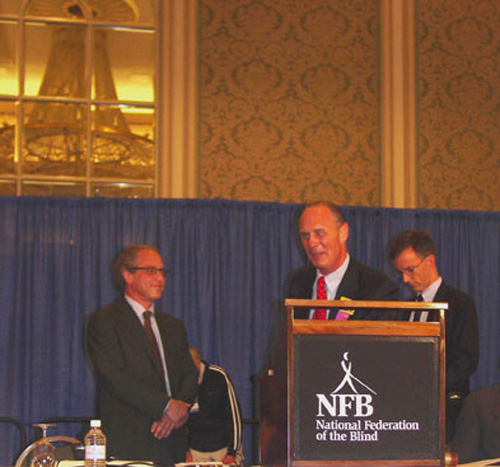

Caption: Jim Gashel (at podium), executive director of NFB, introduces Ray Kurzweil (left) at the unveiling of the Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader.

Enhanced Independence

James Gashel, NFB's executive director for strategic initiatives, has led the user interface side of the project and is an ardent devotee of the Reader. "I wouldn't have said this in 1975," he explained, "but this technology, probably because of its portability, actually enhances a blind person's independence." Why did he say that? If a person who is blind manages to use an ATM and withdraw cash or check his or her balance, the person usually puts aside the printed receipts until a sighted person can read them. With the Reader, Gashel said, he now can routinely confirm that information immediately, reading for himself the receipt that states the amount he has withdrawn or deposited or the amount of his account balance. Similarly, in restaurants, he now regularly reads the menu, the bill, and his payment receipt with the Reader.

Caption: The Reader can read the receipt of a transaction at an ATM.

Caption: Jim Gashel using the Reader to read a restaurant menu.

Built by People Who Are Blind

The Reader consists of software that combines an off-the-shelf PDA and a digital camera into one device that literally snaps a picture of a page of print and then reads it aloud (for an evaluation of the Reader, see Darren Burton's article, "Reading by Hand," in this issue). While the engineers at Kurzweil Technologies developed the software and one prototype after another, the NFB tested and tweaked the prototypes, made design suggestions, and wrote the documentation. In an unusually wide-reaching testing phase that proved to be an excellent strategy, NFB gave the units to 500 of its members across the country to use in their daily lives. The result, Gashel said, is a product that was clearly designed by people who are blind—with an easier-than-usual interface, excellent documentation, and an enormous database of images for developers to use as benchmarks for upgrades. As the 500 Reader Pioneers (as they were called) snapped images of restaurant menus, memos, magazines, medicine packages, brownie mixes, and credit card bills, many of those images were saved on compact flash cards to be added to the 21-gigabyte and growing database of images.

Caption: The Reader Pioneers tested the Reader by using it in their daily lives.

No tool or piece of technology is a panacea. Although more than half the Reader Pioneers found that the Reader was sufficiently indispensable to the quality of their lives that they purchased their test units, not all were so enthusiastic. Some just sent their test units back. Some testers found the concept of holding the camera level or at the correct angle too difficult to grasp, whereas others found the buttons too small or their need simply not great enough to warrant such an outlay of cash.

What About Braille?

Why did the Reader receive so much attention from the mainstream media? One simple explanation is that it is a product that makes sense to people who know nothing about blindness or the technology that people who are blind use. Sighted people know what a digital camera is, and most understand or use PDAs. To see the Reader in action makes sense, too: Snap the picture of a page of print and then hear the handheld computer read the page aloud.

Gashel applied the same principle to the conviction that purchasing Readers will be a smart economic move for individuals, agencies, or employers. With the Reader, a person who is blind no longer needs to pay for sighted assistance to read his or her mail. Employers are sometimes intimidated by what they believe will be the astronomical expense of hiring someone who cannot read print. Once employers see the Reader demonstrated, the understanding that people who are blind have alternative methods for getting things done takes hold. "For those who think that blind people can't fight their way out of a paper bag," Gashel quipped, "the Reader helps make us believable. They see it work, and it's somewhat intuitive—it's a camera that talks!"

One slight negative in the blitz of media coverage was the occasional false assumption that braille would now be replaced. Independence and a good quality of life come together when a person who is blind learns to use a variety of tools and techniques. Mixing and matching these skills is part of the formula. In the case of braille, many users take the memory cards that hold printed items that the Reader has snapped and processed and put them in a BrailleNote, PAC Mate, or Braille Sense to read or edit in braille. As Gashel put it, "The Reader actually enhances my use of braille."

When the product was ready to be put on the market, all the parties thought that a separate company was necessary. Thus, K-NFB Reading Technology was born. Units can be purchased from either the NFB or from Kurzweil Educational Systems, but the proceeds (much of which are used for ongoing development) are funneled into the newly formed entity.

Unofficial Predictions

Since the beta version 2.5.4, the Reader has gone through enough stages to reach version 3.0.5 by mid-September 2006. One welcome addition to this latest version is the ability to transfer text files to another device for viewing. Another is an additional voice. The units now offer a choice of Voice 1 or Voice 2—Eloquence or RealSpeak.

What additions may be expected within the next 12-18 months? One is that after reading your ATM receipt, the Reader will be able to identify your money. Another is a probable Spanish version, in a first step toward making the device available to people who are blind who speak languages other than English. Color identification may be added, and the unit may become even smaller. These are not official Kurzweil predictions, but speculations by others involved in the project.

As Gashel put it, "This design has the input of blind people written all over it. Blind people helped shape it, and they and the NFB will continue to drive its development."