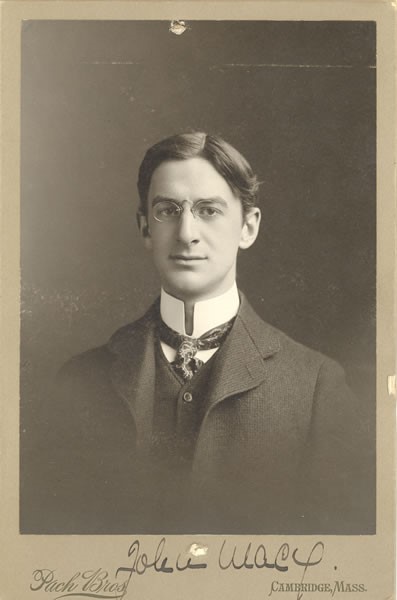

This head and shoulders photographic portrait is of John Albert Macy, circa 1900. He wears glasses and faces the camera dressed in a jacket, vest, necktie, and high collar. Photo credit: Pach Brothers, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

John became Anne's suitor and a frequent visitor to Wrentham. Anne was deeply, passionately in love:

Dearest Heart:-

...I am always a little shivery when you leave me, as if the spirit of death shut his wings over me; but the next moment the thought of your love for me brings a rush of life back to my heart....

....I sat a long time thinking of you, and trying to find a reason for your love for me. How wonderful it is! And how impossible to understand! Love is the very essence of life itself. Reason has nothing to do with it! It is above all things and stronger! For one long moment I gave myself up to the supremest happiness—The certainty of a love so strong that fate had no dominion over it and in that moment all the shadows of life became beautiful realities...

Nan

And again, in another love letter she writes:

My own dear little Johnny;

I miss you very much. I suppose I should say, in the language of lovers, I think of you oftener than I breathe; but I don't, at least not consciously, though it's conceivable, isn't it, that one may so live in her lover that he becomes a part of the substance of her thoughts.

I'm lonely, but not utterly cast down, thanks to Carl who remembers me in the days of my bereavement. Still there are many lonely hours when I move with the careless majesty of a sometime goddess amid the ruins of joys that have been.

Haven't you had enough of New York? Idling about clubs and going to the opera isn't so very much fun, is it? Aren't you longing to come back to your twelve or fifteen hours of work every day—and me?

Full Transcripts of Letters

Anne's Letter to John A. Macy "Dearest Heart..." (No Date)

Dearest Heart:

I was very sorry to say good-by to you yesterday after the pleasant hours we spent together. The sense of being at home comes to me so deeply when I am near you that I am always a little shivery when you leave me, as if the spirit of death shut his wings over me; but the next moment the thought of your love for me brings a rush of life back to my heart.

The house seemed very empty when I got home in spite of the fact that it held the dearest thing in all the world to me until a few months ago–dear, dear Helen. The evening was beautiful and I took Mrs. Ferreu and Helen out in the canoe. They talked and I thought later after every one had gone to bed I went out on the porch to say good-night to the fragrant, beautiful world lying so quietly under the pines. There was only the sound of one bird talking in his sleep to break the stillness. The lake had lost the glow that earlier in the evening had made it so alluring and looked white and peaceful in the twilight. Somehow, I felt out of sympathy with the calm loveliness of the night my heart was hot and impatient–impatient because the repression and self-effacement of a life-time–and my life seems a century long as I look back upon it–have not stilled its passionate unrest. I sat a long time thinking of you, and trying to find a reason for your love for me. How wonderful it is! And how impossible to understand! Love is the very essence of life itself. Reason has nothing to do with it! It is above all things and stronger! For one long moment I gave myself up to the supremest happiness. The certainty of a love so strong that fate had no dominion over it and in that moment all the shadows of life became beautiful realities. Then I groped and stumbled my way back to earth again–the dreary flat earth where real things are seldom beautiful.

Dearest this is the first letter I have written to you and I am afraid I have said things in it which you will not like you will say, we have no right to rest present happiness by harping on possible sorrow. It is because your love is dear to me beyond all dreamt of dearness that I rebel against the obstacles the years have built up between us. But you will not leave off loving me will you–not for a long time at least.

Have you any engagement for Saturday evening? Because Helen and I are going to spend Saturday night at 14 Coolidge Avenue and if you should find it possible to call you would make us very happy. Let me know if we may expect you. I forgot to say why we are going to Cambridge. I find that Mr. Fearin's steamer arrives about eight Sunday morning too late for him to catch the 8.15 tram to Wrentham. It would be awfully dull for the poor chap in Boston all day so I thought we would meet him at the Parker House about 10 o'clock, breakfast there and then take the trolley to Wrentham. If the day is pleasant he will enjoy the ride through the country. Besides this arrangement gives me an opportunity to see you sooner than I expected and I seem to have more need than usual to see you. I kiss you my own John and I love, you. I love, you. I love you.

Nan

July Second

Anne's Letter to John A. Macy "My Own Dear Little Johnny..." (No Date)

My own dear little Johnny:

I miss you very much. I suppose I should say, in the language of lovers, I think of you oftener than I breathe; but I don't, at least not consciously, though it's conceivable, isn't it, that one may so live in her lover that he becomes a part of the substance of her thoughts.

I'm lonely, but not utterly cast down, thanks to Carl who remembers me in the days of my bereavement. Still there are many lonely hours when I move with the careless majesty of a sometime goddess amid the ruins of joys that have been.

Haven't you had enough of New York? Idling about clubs and going to the opera isn't so very much fun, is it? Aren't you longing to come back to your twelve or fifteen hours of work every day–and me?

I'm going to college this week. Just think, I was idle nearly four weeks! So far I haven't been able to take up my work in good earnest. My eyes refuse to read, and my mind won't think. It's full of impatience to do things; but nothing comes of it. I don't know when this imbecility will cease. Perhaps it's the result of my having lost certain customary visits–and other things.

I must confess to you the cruel conviction that is growing upon me, (I know I shall have your scholarly sympathy) that I can't much longer bear up under Kittredge's word-cannonade. They talk of victims of war, of epidemics; but alas, who remembers the battle-fields of education? Three times a week I drink in desperation at every pore, until I feel–but I smell a mixed metaphor, and Shakespeare, it seems, has a "corner" on them. I wish he had a "corner" on the interpretation of his works. It costs one nothing to wish for much–I wish you were here! I've convinced myself deeply and once for all of one thing; but I don't think it's advisable to tell you all my convictions. That's all.

Nan