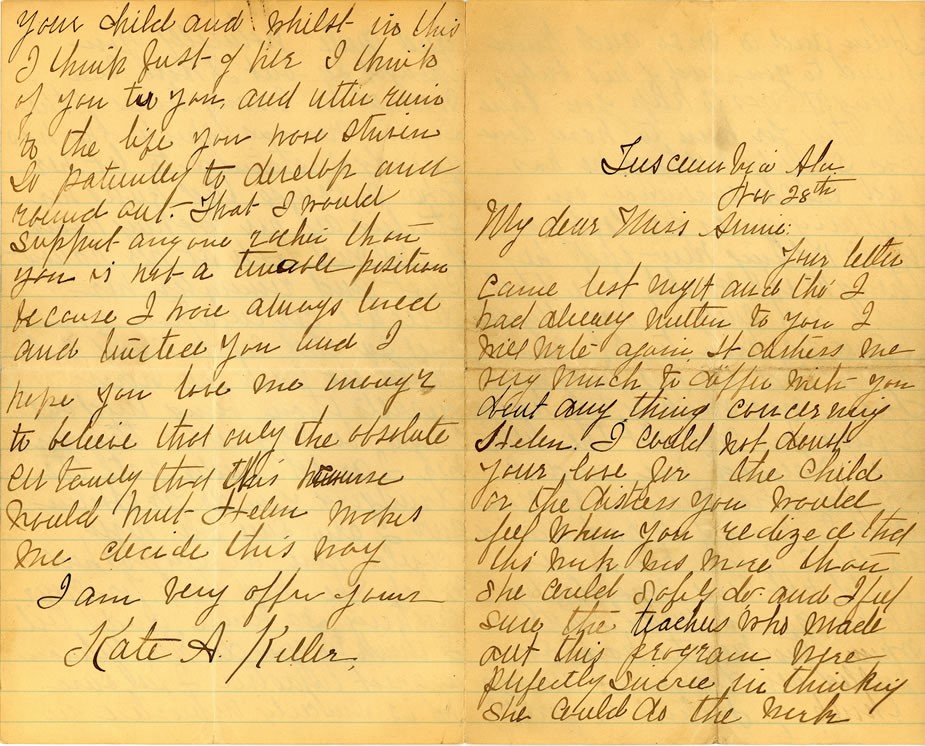

Photo of a letter written by Kate A. Heller in Tuscumbia, Alabama, to Anne Sullivan in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1897. The letter is transcribed below.

Once Helen's abilities were known, the general public and even some scholars believed them to be too extraordinary for a deaf-blind child. In 1891, Anne and Helen's detractors were given information that seemed to prove them right. Anne had sent Michael Anagnos, the Director of the Perkins School for the Blind, a story by Helen entitled The Frost King.

Helen's story was very similar to one written by Margaret Canby. Helen was accused of plagiarism. Alexander Graham Bell and Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain), another of Anne and Helen's supporters, came to their defense quickly. Both men said that we all unconsciously plagiarize. Those who made the charge assumed that Anne, not Helen, had read Canby's book. That led to the belief that Anne must be shaping Helen's thoughts and opinions. In fact, Helen had come across Canby's book many years before at a friend's house. Without realizing it, she had made the story a part of her own thoughts.

In 1897, there was a still more dramatic example of the disagreement over what information Anne was giving Helen. A year earlier, paid for by private, philanthropic funding, Anne and Helen enrolled in the Cambridge School for Young Ladies in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The purpose was to prepare Helen for entrance examinations to Radcliffe College. By the fall of 1897 a dispute had arisen between the school's director, Arthur Gilman, and Anne. Gilman believed that Anne had too great a control over Helen. He wrote to Mrs. Keller that Anne was overworking Helen. He claimed that her health was suffering as a result. He showed Anne a telegram from Mrs. Keller. It authorized him to separate Anne from Helen; Gilman was to take charge of Helen.

Helen and her sister Mildred, who was visiting at the time, refused to follow Gilman to his home without Anne, who left the school that night. Anne sent telegrams to several people, among them Mrs. Keller, Dr. Bell, and philanthropist Eleanor Hutton. Anne returned the next day and refused to leave the school until she had seen Helen and Mildred. She then went with the girls to the house where they lived. All three were forbidden to leave the premises. Joseph E. Chamberlin, a friend of Anne and Helen's, met with Gilman and convinced him to let Anne and the girls stay with him. In the meantime, Mrs. Keller arrived. So did Alexander Graham Bell's assistant at the Volta Bureau, John Hitz. He, following Bell's request, gathered independent reports about what had taken place.

Helen did not return to the school. Instead, she completed her preparatory education at the Chamberlins' home in Wrentham, Massachusetts. No one ever succeeded in separating Anne from Helen after this.

Full Transcript of Letter

Tuscumbia Ala.

Nov 28th

My dear Miss Annie:

Your letter came last night and tho' I had already written to you I will write again. It distress[es] me very much to differ with you about any thing [sic] concerning Helen. I could not doubt your love for the child or the distress you would feel when you realized that this work was more than she could safely do and I feel sure the teachers who made out this program were perfectly sincere in thinking she could do the work and quite naturally you thought so, but I have been warned too many times of the serious nervous shock she has already sustained to let her take a course that keeps her studying all her waking hours, if you will look at her narrow chest, and remember her defective circulation you will see that what many girls can do with no more results than being tired out might be [a] very serious thing for her, I do not under rate [sic] the drudgery you do for Helen and I am sure she never could have accomplished what she has but for your untiring patience and toil, I think too you do Mr. Gilman a great injustice, I feel sure he is sincerely interested in Helen and a wise and kind friend to you, and if his only thought was to keep you there the thing for him to have done was simply nothing, he has had such experience in preparing girls for college it is nothing new that he thought it would take that long, and [surely it was] altogether proper for him to let me know that in his judgment Helen was working too hard, however his was not the letter that alarmed me and I should have written to you and to him if I had received no letter from him; he could not very consistently let her go on until Christmas when two months had so pulled her down. I always think of Helen as partly your child and whilst in this I think first of her I think of you too[?], and utter ruin to the life you have striven so patiently to develop and round out[?]. That I would support anyone rather than you is not a tenable position because I have always loved and trusted you and I hope you love me enough to believe that only the absolute certainty that this course would hurt Helen makes me decide this way[.]

I am very [two or three illegible words]

Kate A. Keller