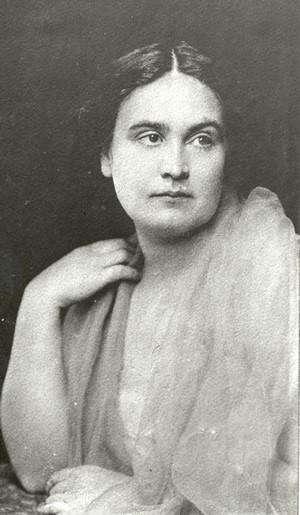

Half-length photographic portrait of Anne, circa 1912. This portrait of Anne shows her from the waist up. Her head is turned to her left, as is her pensive gaze. She appears to be wearing a dress with a shawl of sheer material around her shoulders. Her left arm rests lightly on a table in front of her. Her right elbow leans on the table with her forearm bent upward toward her shoulder. Her hand touches the fabric at her neck.

Anne's first year in Tuscumbia is beautifully described in the series of letters she wrote to Sophia Hopkins—Anne's wealthy patron from her days at Perkins. The letter excerpted here illustrates Anne's skill as a writer:

...dear, I am glad that my success has been such a gratification to you. I thank you from the bottom of my heart for the mother-love you gave me when I was a lonely, troublesome schoolgirl, whose thoughtlessness must have caused you no end of anxiety. It is a blessed thing to know that there is some one [sic] who rejoices with us when we are glad, and who takes pride in our achievements. I know you feared that my quick temper and saucy tongue would make trouble for me here; but I am glad to be able to tell you, at the end of the first year of my independence, that I have lived peaceably with all men and women too. There have been murder and treason and arson in my heart; but they haven't got out, thanks to the sharpness of my teeth which have often stood guard over my tongue.

Full Transcript of Letter

Anne's Letter to Sophia C. Hopkins (March 4, 1888)

Tuscumbia, Alabama, March 4, 1888

My dear; –It was a year ago yesterday that I arrived in Tuscumbia. Did you realize it?

How forlorn and weary I was, nobody, not even you can imagine. I remember how the conductor on the train from Chattanooka [sic] tried to comfort me. He noticed that I cried a great deal, and stopped to ask, "Any of your folks dead, young lady?" His voice was so kind, I could not help telling him a little of my trouble, and he did his best to cheer me, telling me that I would find the southern people most kind and hospitable. When the train stopped at Tuscumbia, the thought flashed through my mind, "Here I am more than a thousand miles from any human being I ever saw before!" But somehow I was not sorry that I had come. I felt that the future held something good for me. And the loneliness in my heart was an old acquaintance. I had been lonely all my life. My surroundings only were to be different.

The first person who spoke to me as I stepped from the train was James Keller, Captain Keller's eldest son, and although he simply spoke my name with a rising inflection, I knew instinctively that we should never be good friends. He said Mrs. Keller was in the carriage waiting for me. When she spoke, a great weight rolled off my heart, there was such sweetness and refinement in her voice. It is a wonder how much of one's character and disposition is revealed in one's voice. There is no doubt in my mind that the voice is a truer index to character than the face. We learn to control the expression of our features; but very few ever succeed in controlling their voices.

I thought, as we drove to my new home through the little town of Tuscumbia, which was more like a New England village than a town; for the roads–there were no streets–were lined with blossoming fruit-trees, and the ploughed fields smelt good, (I think the earthy smell is the best of all spring odors) "Certainly this is a good time and a pleasant place to begin my life-work." When Mrs. Keller pointed out her house at the end of a long, narrow lane, I became so excited and eager to see my little pupil, that I could scarcely sit still in my seat. I felt like getting out and pushing the horse along faster. I wondered that Mrs. Keller could endure such a slow beast. I have discovered since that all things move slowly in the South. When at last we reached the house, I ran up the porch-steps, and there stood Helen by the porch-door, one hand stretched out, as if she expected some one to come in. Her little face wore an eager expression, and I noticed that her body was well formed and sturdy. For this I was most thankful. I did not mind the tumbled hair, the soiled pinafore, the shoes tied with white strings–all that could be remedied in time; but if she had been deformed, or had acquired any of those nervous habits that so often accompany blindness, and which make an assemblage of blind people such a pitiful sight, how much harder it would have been for me! As it was, I knew the task I had set myself would be difficult enough.

I remember how disappointed I was when the untamed little creature stubbornly refused to kiss me and struggled frantically to free herself from my embrace. I remember, too, how the eager, impetuous fingers felt my face and dress and my bag which she insisted on opening at once, showing by signs that she expected to find something good to eat in it. Mrs. Keller tried to make Helen understand by shaking her head and pointing to me that she was not to open the bag; but the child paid no attention to these signs, whereupon her mother forcibly took the bag out from her hands. Helen's face grew red to the roots of her hair, and she began to clutch at her mother's dress and kick violently. I took her hand and put it on my watch and showed her that by pressing the spring she could open it. She was interested instantly, and the tempest was over. Then I led her to my room, and she helped me remove my hat, which she put on her own head, tilting it from side to side in imitation, I learned afterwards, of her Aunt Eve. When the hat was put away, we opened my bag, and Helen was much disappointed to find nothing but toilet articles and clothing. She put her hand to her mouth repeatedly and shook her head with ever greater emphasis as she neared the bottom of the bag. There was a trunk in the hall, and I led Helen to it and by using her signs I tried to tell her that I had a trunk like it, and in it there was something very good to eat. She understood; for she put both her hands to her mouth and went through the motion of eating something she liked extremely, then pointed to the trunk and to me, nodding her head emphatically, which meant, I suppose, "I understand you have some candy in your trunk," and ran down-stairs to her mother, telling her by the same signs what she had discovered. This was my introduction to that bit of my life now out there on the piazza, building queer, shaky houses out of blocks of wood.

I need not tell you, dear, that this has been a hard year; but I do not forget the many pleasant spots in it. I have lost my patience and courage many, many times; but I have found that one difficult task accomplished makes the next easier. My most persistent foe is that feeling of restlessness that takes possession of me sometimes. It overflows my soul like a tide, and there is no escape from it. It is more torturing than any physical pain I have ever endured. I pray constantly that my love for this beautiful child may grow so large and satisfying that there will be no room in my heart for uneasiness and discontent.

And, dear, I am glad that my success has been such a gratification to you. I thank you from the bottom of my heart for the mother-love you gave me when I was a lonely, troublesome schoolgirl, whose thoughtlessness must have caused you no end of anxiety. It is a blessed thing to know that there is some one who rejoices with us when we are glad, and who takes pride in our achievements. I know you feared that my quick temper and saucy tongue would make trouble for me here; but I am glad to be able to tell you, at the end of the first year of my independence, that I have lived peaceably with all men and women too. There have been murder and treason and arson in my heart; but they haven't got out, thanks to the sharpness of my teeth which have often stood guard over my tongue.

The arrogance of these southern people is most exasperating to the northerner. To hear them talk, you would think that they had won every battle in the Civil War, and that the Yankees were little better than targets for them to shoot at. But for all that, they are uniformly kind and courteous, and I shall remember with gratitude as long as I live their gentleness and forbearance under conditions that tried the souls of all concerned.

Indeed, I am heartily glad that I don't know all that is being said and written about Helen and myself. I assure you, I know quite enough. Nearly every mail brings some absurd statement printed or written. The truth is not wonderful enough to suit the newspapers; so they enlarge upon it and invent ridiculous embellishments. One paper has Helen demonstrating problems in Geometry by means of her playing blocks. I expect to hear next that she has [letter ends here].