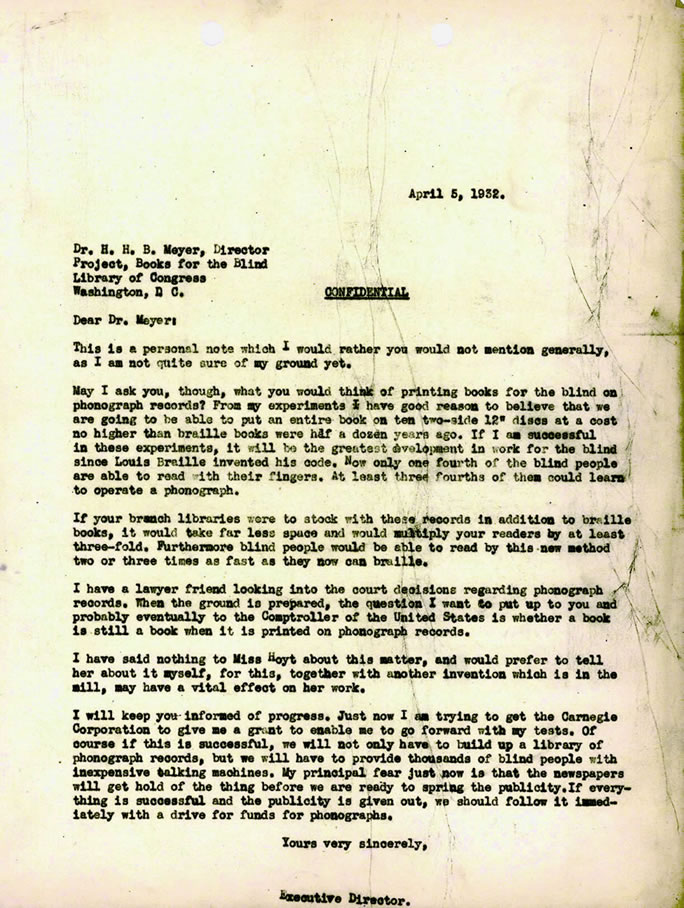

Confidential letter from Robert B. Irwin, Executive Director at the American Foundation for the Blind, to H. H. B. Meyer, Director, Project, Books for the Blind, Library of Congress, informing him of the potential of recordings for the blind and asking him whether the Library would be interested in stocking Talking Books, April 5, 1932. Talking Book Archives, American Foundation for the Blind.

The Pratt-Smoot Act of March 1931 authorized the Library of Congress to administer a project in which selected libraries would "serve as local or regional centers for the circulation of books" to adults with vision loss. Eighteen libraries were chosen to distribute the books, and the Library of Congress selected fifteen titles to be brailled. This was the beginning of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped.

This distribution system was indispensable to the success of the Talking Book project. Displayed on this page is a letter that AFB Executive Director Robert B. Irwin wrote in April 1932 to H. H. B. Meyer at the Library of Congress asking him to consider producing books on records. Meanwhile, the American Foundation for the Blind lobbied the federal government for funding to distribute Talking Books. On March 3, 1933, a law was passed setting aside $10,000 for Talking Books out of the $100,000 allocated to the Library of Congress to provide books to adults with vision loss. U.S. President Herbert Hoover signed the bill into law on the following day, the last day of his presidency.

However, the Library of Congress would not assign this money until it was certain that enough Talking Book machines were readily available to listeners with vision loss. As a result, AFB sent field agents to local state agencies for the blind, and organized fund-raising activities to pay for machines to be distributed within local communities.

Full Text of Letter

April 5, 1932

Dr. H.H.B. Meyer, Director

Project, Books for the Blind

Library of Congress

Washington, D.C.

CONFIDENTIAL

Dear Dr. Meyer:

This is a personal note which I would rather you would not mention generally, as I am not quite sure of my ground yet.

May I ask you, though, what you would think of printing books for the blind on phonograph records? From my experiments I have good reason to believe that we are going to be able to put an entire book on ten two-side 12" discs at a cost no higher than braille books were half a dozen years ago. If I am successful in these experiments, it will be the greatest development in work for the blind since Louis Braille invented his code. Now only one fourth of the blind people are able to read with their fingers. At least three fourths of them could learn to operate a phonograph.

If your branch libraries were to stock with these records in addition to braille books, it would take far less space and would multiply your readers by at least three-fold. Furthermore, blind people would be able to read by this new method two or three times as fast as they now can braille.

I have a lawyer friend looking into the court decisions regarding phonograph records. When the ground is prepared, the question I want to put up to you and probably eventually to the Comptroller of the United States is whether a book is still a book when it is printed on phonograph records.

I have said nothing to Miss Hoyt about this matter, and would prefer to tell her about it myself, for this, together with another invention which is in the mill, may have a vital effect on her work.

I will keep you informed of progress. Just now I am trying to get the Carnegie Corporation to give me a grant to enable me to go forward with my tests. Of course, if this is successful, we will not only have to build up a library of phonograph records, but we will have to provide thousands of blind people with inexpensive talking machines. My principal fear just now is that the newspapers will get hold of the thing before we are ready to spring the publicity. If everything is successful and the publicity is given out, we should follow it immediately with a drive for funds for phonographs.

Yours very sincerely,

Executive Director