The chaos surrounding the 2000 presidential election clearly illustrated the need to modernize our nation's election systems, and several manufacturers have developed electronic voting machines to eliminate the inaccuracies involved with paper and "chad-style" ballots. These machines use electronic ballots displayed on computer screens, and the ballots are counted automatically. Since it is estimated that 500,000 of these machines, costing between $2,000 and $5,000, would need to be purchased across the United States, it could be a multi-billion-dollar process to bring our nation up to date.

To help ensure that people who are blind or visually impaired are not forgotten as this modernization occurs, we gathered four machines that are on the market and evaluated their usability and accessibility. The machines were the iVotronic from Election Systems & Software (Figure 1), the AVC Edge from Sequoia Voting Systems (Figure 2), the eSlate from Hart InterCivic (Figure 3), and the Vote-Trakker from Avante International Technology (Figure 4). Fifteen people, ranging in age from 14 to 64, acted as testers—nine who were blind and six who were visually impaired.

How Could a Machine Earn Our Vote?

A truly accessible voting machine would allow a blind or visually impaired person to vote secretly and verifiably, eliminating the need for an assistant. Sighted voters use modern voting machines by simply touching the area corresponding to the candidate of their choice on an electronic touch-screen display. To use these machines, a blind person reviews the ballot via speech output through headphones and uses buttons to scroll through the ballot and choose candidates. The most important accessibility features are these:

- Speech quality and whether the speech is produced via human voice recordings or synthetic speech.

- Clarity of both printed and spoken instructions.

- Controls that are identifiable tactilely or have braille.

- A means of avoiding under-voting or over-voting.

- User control of font size and screen contrast.

- The ability to use visual and audio voting simultaneously.

- Overall ease of use.

These voting machines must be easy and quick to understand and use by all voters, from the most computer savvy to those whose experience with technology goes no further than the telephone.

We do not have specific prices for the machines. The prices are negotiated and can vary greatly from contract to contract, depending on the quantity purchased and other products purchased by municipalities, such as ballot-preparation, ballot-counting, and voter registration services.

How Do the Machines Stack Up?

iVotronic

The iVotronic touch-screen voting unit is incorporated into a private, sturdy, portable voting booth that could fold up and be rolled on its wheels. The voting unit can be removed and placed on the lap of a voter using a wheelchair or taken out to the street in areas that allow curbside voting. The touch-screen display measures 9.75 inches by 7.25 inches, and the unit has four buttons that blind voters use to navigate and mark the ballot. Three of these buttons are on the panel in front of the touch screen, including two yellow Up and Down triangular buttons. To the right of these two buttons is a green diamond-shaped Select button. In the middle of the panel in back of the touch screen is a black oval Vote button. A red light in this button flashes when it is time to cast the final ballot.

Caption: iVotronic.

This system uses a hierarchical navigation process that was confusing to some of our testers. Initially, the voter is placed in the top level, or contest level, of the hierarchy, then uses the yellow Up and Down arrows to move from contest to contest, and presses the Select button to enter a race. The voter is now in the bottom, or candidate level, of the hierarchy and again uses the Up and Down buttons to move from candidate to candidate. The voter then presses the Select button to choose the candidate of his or her choice. The problem is that if a voter moves past the last candidate in a race, the system takes him or her up a level in the hierarchy to the contest level, positioned on the next race. So, the voter would have to move back up to the race he or she was working on originally and again press the Select button to move back down into the candidate level. The iVotronic does have write-in capabilities, but our sample ballot did not offer this option. One feature that we found truly advantageous was the fact that this unit allows the voter to vote at his or her own pace. You can pause to think, or you can scroll quickly through the ballot.

Evaluating this unit against the criteria we think are the most important, we found that the speech output is produced via high-quality, easily understood human voice recordings. The instructions are clear and informative, but our testers suggested that a better job should be done of describing the hierarchy system. The four buttons that are used to navigate and mark the ballot are easy to locate and identify tactilely. They have unique shapes and contrasting colors, but the braille labels are placed a bit too close to some of the buttons, making them slightly difficult to read. The unit is engineered not to allow overvoting, and the voter is reminded, before casting a final ballot, if a ballot is not fully completed and is given the chance to review or change selections.

The touch-screen interface is easy to use, and the instructions are clear, but the user cannot control the font size. The print is in a 14-point font, which was too small for our visually impaired testers. This unit does not allow voters to change the contrast of the print, and our visually impaired testers would have preferred the ability to change to white print on a black background. In addition, the on-screen display goes away when speech output is used, and our visually impaired testers disliked this feature, preferring the ability to use both vision and speech output simultaneously.

AVC Edge

The AVC Edge is another touch-screen unit. The voting unit is consolidated into its own portable voting booth, but the booth is not as sturdy as the iVotronic booth and does not offer quite as much privacy in its design. Although the touch screen does not detach for curbside voting, the booth does have a wide stance for wheelchair access. The touch-screen display measures 9 inches by 12 inches, and can be adjusted to an angle that is more easily reached for seated voters. Voters who are blind use a handheld control box featuring four tactilely identifiable buttons labeled in braille. The top right button is a square blue Help button, the bottom right button is a red round Select button, and on the left are two triangular buttons pointing Up and Down. The top button is green and is labeled Next, and the bottom one is yellow and is labeled Back.

Caption: AVC Edge.

The AVC Edge uses a hierarchical system similar to the iVotronic interface. We found it slightly easier to use because it does not automatically take you to the next contest when you scroll past the last candidate of a contest. The Help button is context sensitive. However, we found a quirk in the Help system that caused confusion for our testers. After hearing the Help message, the voter is taken all the way back to the beginning of the ballot. The manufacturer has promised to fix this problem. We liked the write-in feature, in which the voter uses the Next and Back buttons to scroll through the alphabet and select letters to spell out the name of the candidate of his or her choice. This unit also allows the voter to vote at his or her own pace, which pleased our testers.

This unit performs well when measured against the criteria we found to be important, but again there is room for improvement. The speech output is produced via human voice recordings, but the audio had a bit of static. The visual instructions are clear and informative, but they are on the side of the voting booth, rather than on the screen, and larger print instructions should be made available to visually impaired voters. The buttons are easy to distinguish visually and tactilely, with highly contrasting colors and shapes, and have braille labels. However, the braille is what the manufacturers called "jumbo braille"—slightly larger than standard braille—and some of our testers had trouble reading it. The testers also did not like the handheld control box, preferring controls that would be part of the voting unit itself. The unit does not allow overvoting, and it prompts voters when a choice has not been made in a race to avoid undervoting.

As with the iVotronic, the screen goes black when audio voting begins, and again our testers did not like this feature. However, the manufacturer is working to correct it. Although larger fonts and different contrasts can be programmed into the unit in advance, the user cannot control the font size or contrast.

eSlate

The eSlate voting machine is not a touch-screen unit, so both sighted and blind voters use the same push-button interface. Although it is available with its own voting booth, our test unit did not come with a booth. The unit is portable to accommodate curbside voting. It includes a headphone jack to provide privacy to voters who are blind or visually impaired. In addition, the unit can be controlled by two tactile switches that voters can operate using their elbows or feet, if need be. It also has a port to connect a "sip and puff" device that a person with quadriplegia can use to control the voting unit with his or her mouth.

Caption: eSlate.

The eSlate display screen measures 9.75 inches by 10 inches and features black text on a gray background in a 14-point font. On the top panel of the eSlate, below the screen, are six buttons. On the left, there is a red Cast Ballot button that is round with the top truncated. The rest of the buttons are white, and along the bottom are two triangular buttons pointing left and right, labeled Previous and Next, but they are not intended to be used by blind voters. Above those two buttons is an oval Help button. Next is an Enter button. The last control is a round Select wheel that the voter rotates to scroll through the ballot.

This machine uses a straight linear ballot. Rotating the Select wheel clockwise one notch brings you to the title of the first contest. Subsequent rotations scroll through the candidates for that race, and pressing the Enter button makes or cancels a selection. Scrolling past the last candidate in a particular race takes the voter to the title of the next race and then to the candidates for that race. Our testers found this linear interface easier to use than the hierarchy system of the previous two machines, but a ballot with a lot of contests could require a great deal of scrolling. Our testers also liked the context-sensitive Help. Pressing the Help button twice sends a message alerting the poll worker that the voter requests assistance. Like the AVC Edge and iVotronic units, this machine has the user-friendly feature of allowing the voter to control the pace of voting. Although the ballots we used did not feature write-in choices, the eSlate does have write-in capabilities.

This unit performs well when measured against the criteria we found to be important, but again there is room for slight improvement. The speech output is high-quality human voice recording, and the instructions are clear and informative, especially with the context-sensitive help. The buttons had contrasting shapes and colors with easy-to-read braille labels. The unit does not allow over-voting, and a review page lets the voter know if a choice was not made in a certain contest. Like all the other units we tested, this one does not allow the voter to control the font size or screen contrast. However, the manufacturer reports having had success placing optical page magnifiers on top of the screen, and the unit can be configured with an 18-point font at the request of the election official. That configuration must be done in advance. Although the voter cannot change the contrast of the display, all our visually impaired testers liked the fact that the screen does not go black when speech output is used and that they were able to use both visual and audio voting simultaneously.

Vote-Trakker

The Vote-Trakker is a portable touch-screen unit with speech output generated via synthetic speech, rather than human voice recordings. The unit did not come with a voting booth, but it did have a glare guard that folds out over the screen to provide some privacy. The touch screen is 11 inches wide by 8.5 inches high. The interface used by voters who are blind or visually impaired is a modified QWERTY computer keyboard. The Escape, Minus, Enter, and Control keys on the four corners of the keyboard are the primary controls, and these keys are raised about twice as high as the other keys for easy identification. In addition, the arrow keys can be used for scrolling, and the letter keys are used to write in candidates.

Caption: Vote-Trakker.

The speech output is produced by the IBM ViaVoice TTS Runtime speech synthesizer, and the voter is able to adjust the voice rate and pitch. When voting begins, the unit reads the title of the first contest, followed by the names of the candidates. There is a short pause after each candidate's name during which the voter may press the Enter button to choose that candidate. If a voter misses a candidate, he or she can use the arrow keys to scroll back, but if the voter waits too long after the name of the last choice is read, Abstain is entered for that contest, and the voter is taken to the next contest. After the final race is completed, the machine reads a review page with the choices that have been made. After each contest is read, the voter has three seconds to press Enter to go back and change the choice for that contest. The voter can also use the arrow keys on this page, but if you scroll past the last contest, you cannot go back, and the ballot must be cast as is. The manufacturer says that this could be a bug in the system and is checking on it.

Although some of our testers liked the flexibility of being able to adjust the synthetic voice, the non-computer users had reservations about the synthetic computer voice, as well as the computer keyboard. In fact, a blind voter who is not familiar with a QWERTY keyboard would not be able to use the write-in feature. Our testers liked the fact that this machine presents the ballot in a linear fashion, without any confusing hierarchies. However, they did not like the pace at which it leads the voter through the ballot and the fact that they could not scroll back up through the ballot to review previous contests and choices until the end. They also disliked the anxiety they felt when given just a few seconds to take an action. However, the manufacturer told us that the time limits can be extended at the request of the election officials.

Reviewing this machine against the criteria we considered important, we found that the speech output could be a problem. Although the testers with experience with synthetic speech had no problem with it, a recorded human voice would be more usable by a greater number of people. The on-screen and spoken instructions were clear and easy to understand, but the keyboard interface could cause fear for non-computer-savvy voters. The system is well designed not to allow over-voting, and the review page and other prompts during the voting process ensure that under-voting does not occur. Although the font size and contrast were not adjustable, voters who are visually impaired will like the touch-screen voting process because of the large print and highly contrasting colors. Although touch-screen voting was not active during audio voting, the screen did present the visual ballot for review by the visually impaired testers.

And the Winner Is…

Before choosing one particular machine over another, we want to stress that all these systems are a tremendous improvement over the way in which people who are blind or visually impaired currently vote with assistance from friends or poll workers, but there is certainly room for improvement.

We like the eSlate the best because of its overall ease of use owing to its linear ballot style. The runner-up is the iVotronic, edging out the AVC Edge because of clearer speech output and a lesser tendency to cause confusion. Had the AVC Edge's help system not led to the confusion mentioned previously, it would have edged out the iVotronic. Trailing the pack is the Vote-Trakker. Although we found it to be an accessible and usable machine, it loses favor because of difficulties that less technology-savvy voters may encounter with its synthetic speech and computer keyboard interface.

Resources

Voting reform is a hot topic in the United States. Many states have passed voting-accessibility laws; federal voting reform legislation has passed both houses of Congress, and we are now awaiting its final form when it emerges from conference. The bill numbers for this federal legislation are S565 and HR3295 in the Senate and House, respectively, and you can learn more at the web site <http://Thomas.loc.gov>. A grass-roots effort to include disability access in this reform process is being conducted by the American Association of People with Disabilities. Learn more at the web site <www.aapd-dc.org>. You can also call your local election officials or your state's secretary of state office to inquire about accessible voting in your area.

Manufacturer's Comments

Avante International Technology

"Avante designed the VOTE-TRAKKER™ with the desire to remove all issues of voter intent from the election process. The first goal of building a voting machine that would be used independently is sometimes open to the interpretation and skill of the voter. We would like to respond to three features that were described by this article.

- The voice used is synthetic. This can never be received as well as a human voice. However, one must consider that the county has to be able to program last-minute changes.

- Many blind voters have felt the standard keyboard even if they have not used one. This means that they are not touching some custom input device for the first time. When writing in their vote, there is voice feedback for the alphanumeric keys.

- The linear process that the voter must take is the balance when creating a voting machine that will not allow the voter to miss contests or make accidental mistakes. Voters always have three chances to review their choices, the same as sighted voters."

Up-and-coming Candidate

A prototype of a new voting machine is being developed by the TRACE Research & Development Center at the College of Engineering, University of Wisconsin– Madison. The center, known for its research and design efforts in the area of accessibility and universal design, seeks to develop access techniques that can be built into standard information and telecommunication technologies to make them more accessible to and usable by people with physical, sensory, or cognitive disabilities. To increase the use of universal design techniques, the center also makes its ideas and designs available to others who are developing products.

The TRACE prototype voting machine is being engineered for cross-disability access and is being designed with a goal of "discoverability." That is, a voter should be able to use the machine without any instruction from a poll worker. Two elements that are designed to accomplish this goal are a Help button and a key identification feature. The Help button provides context-sensitive help, and holding it down while pressing another key produces a message describing that key's function. Another feature of this unit that caught our attention is the zoom capability. Two buttons are used to zoom in and out—giving the user control of the size of the print on the screen—a feature missing in the units that we evaluated. We also like the fact that visual and audio voting can be done simultaneously. For more information about this prototype, send e-mail to info@trace.wisc. edu or phone 608-263-1156.

Funding for this product evaluation was provided by the Teubert Foundation, Huntington, West Virginia.

****

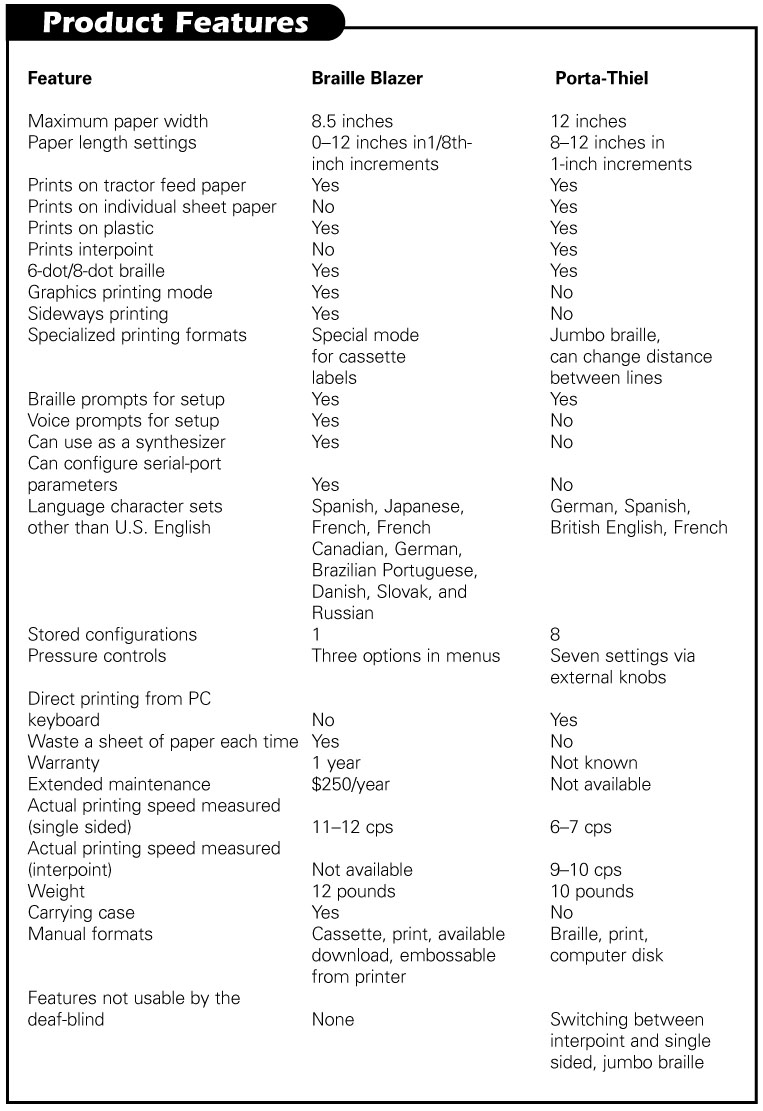

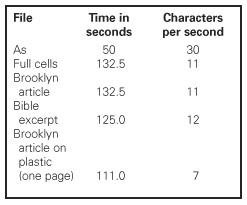

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

****

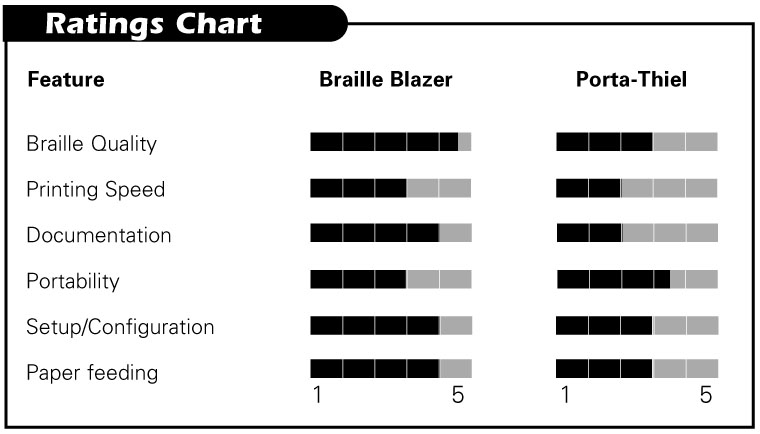

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Product Information

Product: iVotronic

Manufacturer: Election Systems & Software, 11208 John Galt Boulevard, Omaha, NE 68137; phone: 402-593-0101, toll free: 800-247-8683; web site: <www.essvote.com>.

Product: AVC Edge

Manufacturer: Sequoia Voting Systems, 7677 Oakport Street, Suite 800, Oakland, CA 94621; phone: 510-875-1200; web site: <www.sequoiavote.com>.

Product: eSlate

Manufacturer: Hart InterCivic, P.O. Box 80649, Austin, TX 78708-0649; phone: 800-223-HART (4278); web site: <www.hartic.com>.

Product: Vote-Trakker

Manufacturer: Avante International Technology, 70 Washington Road, Princeton Junction, NJ 08550-1012; phone: 609-799-8896; web site: <www.avantetech.com>.