Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Full Issue: AccessWorld September 2002

Product Features

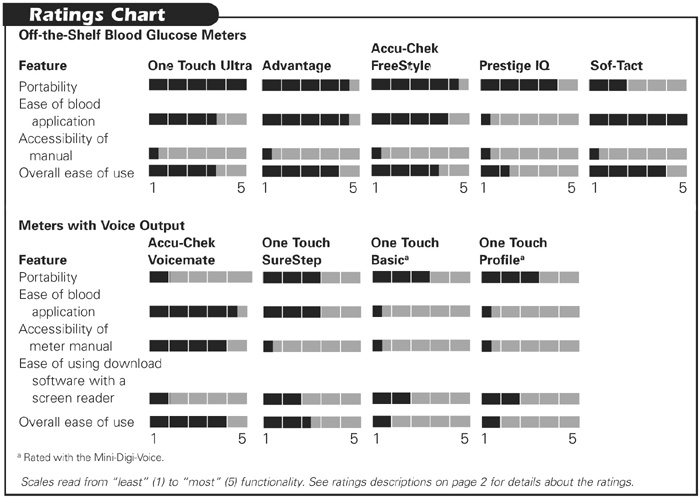

Ratings Chart

Off-the-Shelf Blood Glucose Meters

Portability: One Touch Ultra: 5; Advantage: 4.5; Accu-Chek FreeStyle: 4.5; Prestige IQ: 4; Sof-Tact: 2, Ease of blood application: One Touch Ultra: 3.5; Advantage: 4.5; Accu-Chek FreeStyle: 4; Prestige IQ: .5; Sof-Tact: 5, Accessibility of manual: One Touch Ultra: .5; Advantage: .5; Accu-Chek FreeStyle: .5; Prestige IQ: .5; Sof-Tact: .5, Overall ease of use: One Touch Ultra: 3.5; Advantage: 4; Accu-Chek FreeStyle: 3.5; Prestige IQ: 1.5; Sof-Tact: 4.

aRated with the Mini-Digi-Voice.

Meters with Voice Output

Portability: Accu-Chek Voicemate: 1; One Touch SureStep: 3; One Touch Basica: 3; One Touch Profilea: 3, Ease of bloodapplication: Accu-Chek Voicemate: 4.5; One Touch SureStep: 3; One Touch Basica: .5; One Touch Profilea: .5, Accessibility of meter manual: Accu-Chek Voicemate: 3; One Touch SureStep: .5; One Touch Basica: .5; One Touch Profilea: .5, Ease of using download software with ascreen reader: Accu-Chek Voicemate: 1; One Touch SureStep: 2; One Touch Basica: 2; One Touch Profilea: 2, Overall ease of use: Accu-Chek Voicemate: 4; One Touch SureStep: 3.5; One Touch Basica: 1; One Touch Profilea: 1.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Ratings

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

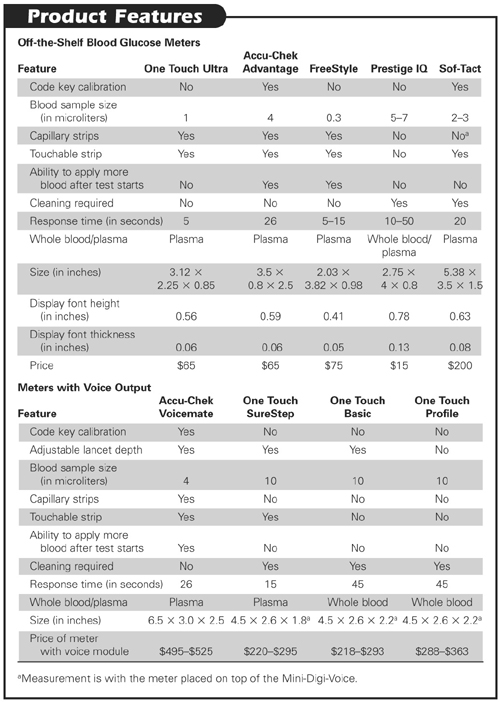

Product Features

aMeasurement is with the meter placed on top of the Mini-Digi-Voice.

Off-the-Shelf Blood Glucose Meters

Code key calibration: One Touch Ultra: No; Accu-Chek Advantage: Yes; FreeStyle: No; Prestige IQ: No; Sof-Tact: Yes, Blood sample size (in microliters): One Touch Ultra: 1; Accu-Chek Advantage: 4; FreeStyle: 0.3; Prestige IQ: 5–7; Sof-Tact: 2–3, Capillary strips: One Touch Ultra: Yes; Accu-Chek Advantage: Yes; FreeStyle: Yes; Prestige IQ: No; Sof-Tact: Noa, Touchable strip: One Touch Ultra: Yes; Accu-Chek Advantage: Yes; FreeStyle: Yes; Prestige IQ: No; Sof-Tact: Yes, Ability to apply more blood after test starts: One Touch Ultra: No; Accu-Chek Advantage: Yes; FreeStyle: Yes; Prestige IQ: No; Sof-Tact: No, Cleaning required: One Touch Ultra: No; Accu-Chek Advantage: No; FreeStyle: No; Prestige IQ: Yes; Sof-Tact: Yes, Response time (in seconds): One Touch Ultra: 5; Accu-Chek Advantage: 26; FreeStyle: 5–15; Prestige IQ: 10–50; Sof-Tact: 20, Whole blood/plasma: One Touch Ultra: Plasma; Accu-Chek Advantage: Plasma; FreeStyle: Plasma; Prestige IQ: Whole blood/plasma; Sof-Tact: Plasma, Size (in inches): One Touch Ultra: 3.12; × 2.25 × 0.85; Accu-Chek Advantage: 3.5 × 0.8 × 2.5; FreeStyle: 2.03; × 3.82; × 0.98; Prestige IQ: 2.75 × 4 × 0.8; Sof-Tact: 5.38 × 3.5 × 1.5, Display font height (in inches): One Touch Ultra: 0.56; Accu-Chek Advantage: 0.59; FreeStyle: 0.41; Prestige IQ: 0.78; Sof-Tact: 0.63, Display font thickness (in inches): One Touch Ultra: 0.06; Accu-Chek Advantage: 0.06; FreeStyle: 0.05; Prestige IQ: 0.13; Sof-Tact: 0.08, Price: One Touch Ultra: $65; Accu-Chek Advantage: $65; FreeStyle: $75; Prestige IQ: $15; Sof-Tact: $200.

Meters with Voice Output

Code key calibration: Accu-Chek Voicemate: Yes; One Touch SureStep: No; One Touch Basic: No; One Touch Profile: No, Adjustable lancet depth: Accu-Chek Voicemate: Yes; One Touch SureStep: Yes; One TouchBasic: Yes; One Touch Profile: No, Blood sample size (in microliters): Accu-Chek Voicemate: 4; One Touch SureStep: 10; One TouchBasic: 10; One Touch Profile: 10, Capillary strips: Accu-Chek Voicemate: Yes; One Touch SureStep: No; One Touch Basic: No; One Touch Profile: No, Touchable strip: Accu-Chek Voicemate: Yes; One Touch SureStep: Yes; One TouchBasic: No; One Touch Profile: No, Ability to apply more blood after test starts: Accu-Chek Voicemate: Yes; One Touch SureStep: No; One Touch Basic: No; One Touch Profile: No, Cleaning required: Accu-Chek Voicemate: No; One Touch SureStep: Yes; One TouchBasic: Yes; One Touch Profile: Yes, Response time (in seconds): Accu-Chek Voicemate: 26; One Touch SureStep: 15; One TouchBasic: 45; One Touch Profile: 45, Whole blood/plasma: Accu-Chek Voicemate: Plasma One Touch SureStep: Plasma One TouchBasic: Whole blood One Touch Profile: Whole blood, Size (in inches): Accu-Chek Voicemate: 6.5 × 3.0 × 2.5; One Touch SureStep: 4.5 × 2.6 × 1.8a One TouchBasic: 4.5; × 2.6 × 2.2a One Touch Profile: 4.5 × 2.6 × 2.2a, Price of meter with voice module: Accu-Chek Voicemate: $495–$525; One Touch SureStep: $220–$295; One TouchBasic: $218–$293; One Touch Profile: $288–$363.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Managing Diabetes with a Visual Impairment

The authors would like to thank the Joslin Diabetes Center of St. Mary's Hospital, Huntington, WV, the Marshall Diabetes Center of Cabell Huntington Hospital, Huntington, WV, and Detra Bannister of AFB TECH. Funding for this product evaluation was provided by the Teubert Foundation, Huntington, WV.

Diabetes is a disease in which the body is unable to use and store glucose properly. It is a serious health problem in the United States—16 million people have the disease, and over 5 million of them experience some form of vision loss. Using devices that measure their blood glucose levels enables people to keep those levels within a normal range by taking a dose of insulin or eating a certain food. Blood glucose meters have revolutionized diabetes care by allowing individuals with diabetes to have more active control over their condition.

Why is an accessible blood glucose meter so important? The answer is simple: If you are not able to operate the meter and read the results, the meter is not usable. There are about 30 blood glucose meters on the market, including a few that have speech-output capability or can be used with a separately purchased speech module. Some visually impaired people may be able to use an off-the-shelf meter without speech output, but others with less vision need speech access to test their blood independently.

For this evaluation, we acquired and examined 16 blood glucose meters, including the ones that have speech output capability. We identified which meters to acquire by using published reports and physicians' recommendations. To help us understand the devices, we observed blind or visually impaired people using their blood glucose meters and then interviewed them. We identified the key features to look for in a meter, rated the meters that offer speech output and five that do not, and considered the state of the technology of blood glucose meters, including what next-generation devices may be like.

We first review five off-the-shelf meters to identify those that have the most usable features for people who are visually impaired. We also give you background on how meters work, what to look for, and how the technology will be changing in the coming years. We then review meters that offer speech-output capability and show how blood glucose meters are being used by four visually impaired individuals.

How a Blood Glucose Meter Works

Today's blood glucose meters use an enzyme found in the blood to measure glucose levels. The glucose in a drop of blood placed on a test strip reacts with the enzyme, and this reaction is measured by an electric current generated by the reaction. The conventional means of self-testing one's blood glucose level is the finger stick method. To perform finger-stick blood glucose tests, you need a meter, a lancet device, disposable lancets that enable you to draw a drop of blood in a controlled way, and a set of test strips.

Before you use a blood glucose meter, you need to calibrate it to the test strips—every time you open a new container of test strips and before the first strip is used. Some meters require that you push a button until the number that appears on the screen corresponds to the number located on the test-strip container. Other meters use strips that come with an encoded key or strip that allows you to calibrate the meter by inserting the encoded key or strip into a slot in the meter.

After the test strip is inserted into the meter, a blood sample is obtained using the lancet device. Typically, you draw blood from the tip of the finger, but some newer devices allow you to use the forearm, upper arm, or thigh. Then, blood must be applied to the target area of the test strip, which is tiny—sometimes no larger than a few square millimeters. In 5 to 50 seconds, depending on the device, the blood glucose reading (a two- or three-digit number) appears on the meter's display.

Desirable Features of Blood Glucose Meters

Code Key Calibration

Although test-strip calibration is done only once with each new container of test strips, it can be a hassle to do, especially if you can't see the meter display or the code on the container of test strips. Meters that use an encoded key or strip make life a lot easier.

Adjustable Lancet Depth

Each meter comes equipped with its own lancet device and a few disposable lancets. The lancet depth should be adjustable to control the puncture depth, an important feature for reducing discomfort and the need to repeat the test.

Blood Sample Size

Newer meters usually require from 0.3 to 4.0 microliters of blood—much less than the typical 10.0 microliter sample of older models. Since the manufacturers assume that verification of sufficient blood on the strip will be done visually, a smaller sample size gives the visually impaired user better odds of getting enough blood on the strip and reduces the need for retesting.

Capillary and Touchable Strips

The task of applying blood on a test strip can be difficult. It is particularly hard to do if the strips are so sensitive that you cannot touch the test area of the strips, which is the case with some meters. The task is made much easier if the meter uses touchable strips. In addition, it is also easier to apply blood on a strip if the strips are designed to take advantage of capillary action, which draws the blood on the strip.

Ability to Apply More Blood After the Test Starts

Some meters allow you to apply more blood to the test strip after the initial application, in case not enough was initially applied. This feature diminishes the need for retesting.

Cleaning

To remain accurate, some meters need to be cleaned of residual blood that may have gotten on sensitive parts of the meter. Other meters are designed so that these components are not exposed, thereby eliminating the need for cleaning.

Response Time

The response time is the amount of time it takes the meter to provide a reading after the blood is applied. Shorter times make testing less of a hassle in our fast-paced world.

Whole-Blood versus Plasma Readings

Plasma-calibrated meters convert whole-blood readings to plasma-equivalent values, the standard used by health professionals. Plasma-calibrated meters make it easier for patients and their health care professionals to keep track of their progress.

Size/Portability

Active people need the convenience of being able to put a meter into their pocket or pocketbook. Some meters are as small as a pager, while those with speech modules are much larger but still portable. Though all meters use small LCD screens that are not easy to view, the font size on the screens is typically large and bold.

Accuracy and Consistency

The results of the tests of accuracy and consistency of 11 popular meters were published in the October 2001 issue of Consumer Reports. The article defined consistency as "the ability to give similar readings on successive tests of the same blood sample" and accuracy as "how closely the readings agreed with the standard lab results" (p. 38).

Downloading Capability

All meters have the ability to keep test results in memory. In some, the data can be downloaded to a computer and translated into charts or other simplified forms, which can be a helpful tool for patients and their physicians.

Cost

The average meter costs between $50 and $70, and many come with rebates that can significantly reduce the cost. However, expect to pay 5 to 10 times as much if you need speech. The small test strips on which the blood is applied are also a major cost component, especially if you need to test your blood many times a day. On average, they cost from 65 cents to 90 cents apiece, with a new one needed for each test. The disposable lancets must also be purchased separately, but they cost only a few cents apiece. Health insurance covers all the components but may limit the choices of meters.

Five Off-the-Shelf Blood Glucose Meters

We tested 5 meters from among the 16 we acquired. Three were the top picks by Consumer Reports, and the other 2 were the ones from among the 16 that had the largest fonts. Consumer Reports's highest rated, in rank order, are the One Touch Ultra from LifeScan, the Accu-Chek Advantage from Roche Diagnostics, and the FreeStyle from TheraSense. The meters with the largest fonts from among the 16 we acquired were the Prestige IQ from Home Diagnostics and the Sof-Tact from Medi-Sense. The Prestige IQ was not rated by Consumer Reports, but its predecessor was, and the manufacturer says that the Prestige IQ uses the same testing technology (see Consumer Reports, October 2001, p. 37).

Caption: From left to right: One Touch Ultra, Accu-Chek Advantage, FreeStyle, Prestige IQ, and Sof-Tact.

The figure is a photograph of five blood glucose meters. The meters are arranged with the smallest on the left and the largest on the right.

The Sof-Tact was not rated by Consumer Reports because it is so new. It uses a testing method that combines all the separate steps of blood glucose testing. You press the meter onto the test site (the base of your thumb, your forearm, or your upper arm) and push a button. The meter creates a vacuum against the skin, obtains a blood sample with its built-in lancet, and then applies the blood to its internal test strip. The unit can also function in the standard way, using the finger-stick method. We looked at the Sof-Tact's automated approach to testing.

The advantages of the three meters that were rated the highest by Consumer Reports are that they are all small and lightweight and were rated "very good" in both accuracy and consistency. The accuracy and consistency of the testing technology used in the Prestige IQ was also rated by Consumer Reports; that meter was rated "fair" in accuracy and "poor" in consistency.

Since all meters on the market use LCD displays, none offers particularly good contrast; in addition, the displays cannot be viewed at a side angle, and the screen is not visible outdoors in sunlight. On the positive side, they all use relatively large fonts. The meter with the largest font is the Prestige IQ. Its font is .78 inches tall and .13 inches thick, which is 24% larger in height and 54% thicker than the largest and thickest of the next best, the Sof- Tact. The three meters chosen by Consumer Reports used fonts that were smaller— approximately 18% shorter and 29% thinner than the Sof-Tact.

As for ease of use, we found that the Ultra and the FreeStyle have the fastest response time and use the smallest blood sample. But the Advantage had other useful features: a code key for calibrating the meter, a tactile notch on the test strip to help feel where to apply blood, and the ability to add more blood after testing begins. The Prestige IQ lacks features that make it easy to use. The Sof-Tact is the easiest to use of the meters we tested because it does not require you to apply blood manually on the test strip. Unfortunately, we do not have feedback from users on how well this new device works or whether the testing process is more painful, the same, or less painful than the standard finger-stick method.

The Bottom Line

Off-the-shelf blood glucose meters, such as the One Touch Ultra, the Accu-Chek Advantage, and the FreeStyle, are highly portable, accurate, and consistent. They leave something to be desired when it comes to ease of use and font size, however. The Prestige IQ offers the largest font, but doesn't measure up to the other meters in either ease of use or accuracy and consistency.

The Sof-Tact is the most interesting of the meters we evaluated because its automated approach makes it the easiest to use. However, since it uses new technology, the real test is feedback from users. Until we hear from Sof-Tact users whether they like the device, we prefer to say that it shows much promise. In addition, at present the only data on accuracy is available from the manufacturer by calling 866-763-8228 and requesting a white paper. But if you are in the market for a blood glucose meter and can consider an off-the-shelf system, speak with your physician or certified diabetes educator about the Sof-Tact. Keep in mind that the Sof-Tact is about $200, which is considerably more expensive than the others. If you prefer to stay with the tried and true, we recommend the Accu-Chek Advantage, since it has been well tested and has the most ease-of-use features. Of course, the best way to determine if you can read the display is to view the meter before you buy it.

Meters with Voice-Output Capability

Speech output modules were examined for speech quality, speech controls, and convenience. The criteria we used to evaluate the meters were as follows:

- Does the meter use a code key or strip for calibration?

- Is the lancet depth adjustable to control puncture depth?

- How small is the required blood sample?

- Are the test strips touchable, and do they use capillary action to draw blood onto the strip?

- Does the meter allow for the application of more blood after the test starts?

- Does the meter require cleaning after use?

- How long must you wait to get a reading after the blood is applied?

- Is the meter calibrated for plasma values—the standard used by health care professionals?

- Is the meter small enough to fit in a pocket or pocketbook?

- How accurate and consistent is the meter?

- Can the test data be downloaded to a computer?

- Is the meter priced competitively?

The Accu-Chek Voicemate, by Roche Diagnostics, combines a meter and voice output module in one device. Three other meters on the market—the One Touch SureStep, the One Touch Basic, and the One Touch Profile, all made by LifeScan—can be used with voice modules that are purchased separately. The One Touch Basic and the One Touch Profile are not as up to date as are the One Touch SureStep and the Accu-Chek Voicemate. Although we put them in our Product Feature Chart and Ratings Chart, they don't measure up to the Voicemate and SureStep. The real competition is between the Voicemate and SureStep, and it is these two products that we think buyers should focus on.

Accu-Chek Voicemate

The Accu-Chek Voicemate is composed of the Accu-Chek Advantage blood glucose meter, which is plugged into the Voicemate's speech output module. The one-piece unit is the largest of the systems we examined (6.5 in. × 3.0 in. × 2.5 in.)— small enough to carry around, but too large to fit into a pocket or pocketbook. The Advantage is powered by two lithium batteries. Its screen is slightly smaller than the SureStep, and the font size (½ in. high) is also slightly smaller and not as thick and bold. Voicemate documentation is available on tape and in large print.

Consumer Reports evaluated the Advantage but not the Voicemate's speech module. Overall, the Advantage was rated second best from among 11 blood glucose monitors that it evaluated and was given a "very good" rating on both accuracy and consistency. Consumer Reports defined consistency as "the ability to give similar readings on successive tests of the same blood sample" and accuracy as "how closely the readings agreed with the standard lab results."

However, we noticed that the Advantage that came with the Voicemate looked different from the one purchased separately that was pictured in the Consumer Reports evaluation. We purchased one and found that its screen font was bolder and easier to read and that it is incompatible with the Voicemate's speech module. We contacted Roche Diagnostics and received verification that the separately purchased Advantage differs in packaging details, screen font, and layout, and is incompatible with the Voicemate. We were told that, with the exception of those differences, the technology used in the separately purchased Advantage is identical to the one that comes with the Voicemate.

Caption: From left to right: The Accu-Chek Voicemate and the One Touch SureStep with the Mini-Digi-Voice speech module.

The figure is a photograph of two blood glucose meters.

There is a slot in the Voicemate for a code key for calibrating the meter for test strips. It uses touchable test strips that have a notch cutout to identify tactilely where to apply the blood. In addition, you can apply more blood after the test starts. The Voicemate requires four microliters of blood—less than half the amount used by the SureStep, but considerably more than many meters that do not offer speech output.

The response time can be quite slow, as long as 40 seconds. The Voicemate does not require cleaning, and, as an added extra, it has a built-in insulin vial reader that reads Eli Lilly insulin vials. It has an earphone jack. Memory download requires the purchase of special Accu-Chek software and a cable. We found the software unusable with a screen reader.

The Voicemate enunciates the meter's blood glucose reading only once. It has a repeat button, a feature that is preferable to the annoyance of continuous enunciation, and a thumb wheel control for on/off and setting the volume. The Voicemate can be operated by an external power supply or a nine-volt battery and is not rechargeable. The speech quality is good.

One Touch SureStep

Accessing the One Touch SureStep with speech requires the purchase of a separate voice unit from Science Products (800-888-7400 or 610-296-2111). The SureStep is slightly larger than the Advantage, but when combined with Science Products's smallest voice unit, the Mini-Digi- Voice, it is half the size of the Accu-Chek Voicemate (4.5 in. × 2.6 in. × 1.8 in.). It is powered by two AAA batteries. The documentation is available only in small print.

We purchased the SureStep for $65 and received a $40 rebate. Overall, it was rated fourth best by Consumer Reports and was given a "very good" on consistency and an "excellent" on accuracy. The response time is 15 seconds—better than the Voicemate but not as fast as some others.

Unlike the Voicemate, the SureStep must be calibrated manually by pushing a button until the number on the screen corresponds to the number located on the vial of new strips. Its blood glucose test strips are touchable, but require 10 microliters of blood, and you cannot apply additional blood after the test starts. The unit requires cleaning. Memory can be downloaded with free software, which is available on LifeScan's web site, and you need to purchase a cable. We found the software difficult to use with a screen reader, and some reports it generated were not accessible.

Science Products offers two versions of its Digi-Voice speech module for the SureStep, Basic, and Profile: the Mini-Digi-Voice or the Digi-Voice Deluxe. We prefer the Mini-Digi-Voice, because it is half the size of the Deluxe and costs $75 less. Unlike the Deluxe, the Mini does not have an external power source or an earphone jack and uses only a nine-volt, nonrechargeable battery.

The Mini uses cabling that plugs into the data port of the SureStep. Its speech quality is comparable to that of the Voicemate. However, the Mini's speech is continuous, with no way of silencing it, short of shutting down the SureStep. Turning on the SureStep will automatically turn on the Mini, which is a practical feature. But volume can be adjusted only by selecting one of five setting options that are spoken when the unit is turned on. The speech quality is good.

The Bottom Line

If you need speech output and you want the most up-to-date blood glucose meter, you are limited to two systems. Expect to pay about $260 for the One Touch SureStep with the Mini-Digi-Voice speech module or $495 for the Accu-Chek Voicemate. Check with your health insurance provider to find out if the cost of these units is covered.

The SureStep with the Mini-Digi-Voice module is smaller than the Accu-Chek Voicemate, offers slightly faster response time, and was slightly more accurate in tests done by Consumer Reports. The Accu-Chek Voicemate is easier to use because of such features as code key calibration, capillary strips with a tactile notch, and the use of a smaller blood sample. In addition, it does not require cleaning. Speech access is acceptable in both.

To control diabetes, you need to use a blood glucose meter often. Since the meter is a device that, by the nature of what it does, is somewhat unpleasant to use, we think ease-of-use is extremely important and outweighs a slight difference in accuracy, a longer response time, and a higher cost. The One Touch SureStep used with the Mini-Digi-Voice speech module is a good system, but the Voicemate is our choice because it is easier to use. We are not comfortable recommending systems that are based on the One Touch Profile or the One Touch Basic, since they are not as easy to use as either the Voicemate or the SureStep.

New Developments in Blood Glucose Monitoring

Caesar Eghtesadi

Just on the Market

The GlucoWatch Biographer from Cygnus is a wristwatch-like device that uses a low-frequency electrical current to draw out and measure glucose through the skin at predetermined intervals. It provides readings of up to three times an hour, day or night, for up to 12 hours at a stretch. It also creates a diary of up to 4,000 glucose readings over time. However, it is not designed to replace finger-stick testing entirely and must be calibrated with a blood test daily to identify blood glucose trends accurately. It costs about $2,700 with accessories.

The MiniMed Continuous Glucose Monitoring System from Medtronic MiniMed measures blood glucose levels continuously every five minutes for up to three days. It is an implantable device that is inserted under the skin by a physician. This device supplements, rather than replaces, the finger-stick self-testing that patients now perform. The unit has received FDA approval and is currently available. It costs about $3,000.

The Personal Lasette Plus from Cell Robotics International is the only device that does not rely on lancets or needles for removing blood. It uses a laser system to draw blood from the finger, but the device is not painless. It is said that the pain is comparable to a quick snap from a rubber band. It costs about $1,000. Other laser-based systems are under development, including one from Abbott Labs.

Still in the Lab

Expect to see blood glucose monitoring based on infrared light technology, whereby an infrared beam is able to measure blood glucose levels painlessly. The Diasensor 2000 from Diasense has received approval for use in Europe and is currently under review by the FDA.

Clinical trials are now taking place on the use of ultrasound technology to measure glucose levels across the skin. Sontra Medical has found that a brief (approximately 15-second) application of low-frequency ultrasound can enhance the permeability of skin for up to 12 hours. After the ultrasound treatment, a sensor patch can be applied to the site to monitor the level of transdermal glucose. Blood glucose values would be displayed on a wearable meter.

Just over the Horizon

Glucose sensing using radio waves is a measuring technology that shows much promise. Radio sensing is painless, requires no blood, and takes just a few seconds to complete. This technology is still under development.

ISense Corp. has been working on a real-time sensor that is only four times the size of a human hair. The sensor, inserted underneath the skin for five days, is connected to a small module that can display glucose levels by the minute. ISense Corp. is also developing a wireless connection between the sensor and its module.

Recent developments in telemedicine—the exchange of medical information from one site to another via electronic communications—is another avenue for monitoring and controlling a patient's blood glucose level. Advanced noninvasive techniques for measuring blood glucose, combined with telemedicine, will create a totally new paradigm for monitoring and controlling diabetes.

A New Research Priority

Although these new technologies are truly exciting, what should not be ignored is the need for a cost-effective, noninvasive blood glucose monitoring system with an embedded voice module that is based on a universal design concept—a system that is accessible to all.

Interviews with Four Users of Blood Glucose Meters

Mark Uslan, Karla Schnell, and Angie Spiker

We visited four visually impaired users of blood glucose meters to observe how they used their meters and to interview them. All four have had diabetes for over 20 years and experience fluctuation in their remaining vision. One person was visited at her place of employment, and three were visited at home.

One person tests her blood six to eight times a day. She uses two meters, the Accu-Chek Voicemate at home, and the Accu-Chek Complete outside her home, because she thinks that the Voicemate is too bulky to take anywhere. To read results on the Accu-Chek Complete, she either uses her closed-circuit television (CCTV) or her vision, when possible, or asks someone to read it. She wishes the Accu-Chek Advantage were smaller and the Accu-Chek Complete would have speech output.

Two people use the Glucometer Elite from Bayer. One of the two tests his blood once a day and uses his vision to read the results. He likes using the code key to calibrate the meter and being able to apply more blood after the initial application, but he wishes his meter had a larger screen. The other person tests her blood four times a day and uses her CCTV to read the results. She likes the code key feature and the capillary strip feature. She wishes her meter had speech output.

The fourth person uses the One Touch SureStep from LifeScan. She tests her blood once a day and gets help doing it six days a week. On the one day a week she tests her blood independently, she uses a magnifier to read the results, but has some difficulty getting blood on the test strip. Sometimes she has to repeat testing up to three times. She wishes the process were easier.

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Product Information

Product: One Touch Ultra

Manufacturer: LifeScan, 1000 Gibraltar Drive, Milpitas, CA 95035; phone: 800-227-8862; web site: <www.lifescan.com>. Price: $65.

Product: Accu-Chek Advantage

Manufacturer: Roche Diagnostics, 9115 Hague Road, PO Box 50457, Indianapolis, IN 46256; phone: 800-858-8072; web site: <www.accu-chek.com>. Price: $65.

Product: FreeStyle

Manufacturer: TheraSense, 1360 South Loop Road, Alameda, CA 94502; phone: 888-522- 5226; web site: <www.therasense.com>. Price: $75.

Product: Prestige IQ

Manufacturer: Home Diagnostics, 2400 N.W. 55th Court, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33309; phone: 800-342-7226; web site: <www.prestigesmartsystem.com>. Price: $45.

Product: Sof-Tact

Manufacturer: Abbott Laboratories, Medi-Sense Products, Bedford, MA 01730; phone: 866-763-8228; web site: <www.medisense.com>. Price: $200.

Product: Digi-Voice for One Touch SureStep, Basic, and Profile

Manufacturer: CAPTEK, sold by Science Products, Box 888, Southeastern, PA 19399; phone: 800-888-7400. Price: Digi-VoiceDeluxe $275, Mini-Digi-Voice $199–$219.

Product: Accu-Chek Voicemate System

Manufacturer: Roche Diagnostics, 9115 Hague Road, PO Box 50457, Indianapolis, IN 46256; phone: 800-858-8072; web site: <www.accu-chek.com>. Price: $495 to $525; Accu-Chek Compass Software: $29.99; Interface Cable: $30.

Product: One Touch Basic

Manufacturer: LifeScan, 1000 Gibraltar Drive, Milpitas, CA 95035; phone: 800-227-8862; web site: <www.lifescan.com>. Price: $53; InTouch Software: free download from web site; interface cable: $19.99.

Product: One Touch SureStep

Manufacturer: LifeScan, 1000 Gibraltar Drive, Milpitas, CA 95035; phone: 800-227-8862; web site: <www.lifescan.com>. Price: $65; InTouch Software: free download from web site; interface cable: $19.99.

Product: One Touch Profile

Manufacturer: LifeScan, 1000 Gibraltar Drive, Milpitas, CA 95035; phone: 800-227-8862; web site: <www.lifescan.com>. Price: $113; InTouch Software: free download from web site; interface cable: $19.99.

Product: LHS-7 for the One Touch Profile

Manufacturer: LS&S Group, PO Box 673, Northbrook IL 60065; phone: 800-468-4789; web site: <www.lssgroup.com>. Price: $199.

The Conundrum of PDF Accessibility

Jennifer Sutton wanted to read her graduate school's online alumni newsletter, which is published as a PDF file. She sent the file to a URL that translated the file into text that was compatible with her screen reader. The bad news is that the page jumps for the various articles ran together in a single block of text. Reading it, Sutton recalls, required more concentration because of the irregular formatting.

For Curtis Chong, it was the desire to become more familiar with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) 1040 form, published on the IRS web site as a PDF file. Even with his latest version of screen-reading software, Chong was not able to fill out a 1040 form online. In frustration, he finally printed a hard copy and used a sighted reader to help him complete the form, which also required a handwritten signature.

What Is PDF?

Adobe Acrobat is a product that allows you to create and publish information in portable document format (PDF). Once published and made available on the Internet or on a product CD-ROM, PDF files can be read using the free Adobe Acrobat Reader. Because of its ability to be used on a variety of operating systems and to maintain the format of the print document, PDF has become a popular format in which companies distribute information about products, such as user manuals and troubleshooting guides. Many governmental agencies—such as the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Education—also use PDFs to publish literature and forms.

Section 508 of the Workforce Investment Act of 1998 mandates, among other things, that all electronic information and technology products purchased or provided by a governmental agency must be accessible to people with disabilities; this mandate creates the conundrum of PDF accessibility. Many governmental agencies, publishers, and other providers of information have uploaded many documents on their web sites that are in PDF and hence inaccessible to users who are visually impaired or otherwise unable to read regular print. The accessibility gap, however, is narrowing for three reasons.

First, of course, is the fact that when Section 508 took effect in June 2001, issues of compliance by governmental agencies and sales to these agencies by vendors were catapulted to the fore. Second, in April 2002, AFB, partnering with National Industries for the Blind (NIB) and the American Council of the Blind (ACB), authored a white paper calling attention to the accessibility issues involving PDF. The paper recommends that "accessible formats must always accompany PDF versions of information and data that are made available to the public." Third, these two documents have continued to raise awareness of a greater need for accessibility by Adobe in developing its authoring and reading tools, as well as by developers of screen readers.

"Have we been weak on accessibility? Absolutely," said Rick Brown, senior product manager for Adobe's Acrobat Reader. "When the format came out, accessibility was not considered."

"508 has accelerated the process of creating accessible PDF," adds Christy Hubbard, Adobe's government products marketing manager. "I think the technology industry is taking this issue seriously and is making tremendous strides."

While Adobe's PDF format and its free downloadable, Acrobat Reader, have been around for a decade or so, the unreadability factor was first brought to Adobe's attention in 1997 by the pioneering work of Adobe staffer T. V. Raman. Since the file format was not inherently accessible, Raman found a way to convert documents to text files. The reading technology still doesn't recognize columns and section continuations; thus, Jennifer Sutton's alumni newsletter was translatable into a text block, but a text block with no subdivisions that would make logical sense of the columns and spaces in the original layout.

The white paper, authored by Janina Sajka, AFB's director of technology research and development, and Joe Roeder, senior access technology specialist for NIB, prompted a meeting with Adobe. "We didn't want to get into dueling white papers," Brown said. "We wanted to get all issues out on the table, and I think we all came to a greater understanding of the issues faced by each side."

"PDF is a wonderful format for presenting read-only documents," says George Kerscher, who chairs the Open E-Book Forum and is Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic's executive on loan to the DAISY consortium. "PDF is just not accessible to people who use screen readers. Accessible PDF is an oxymoron."

"The future is how to communicate with someone using PDF with a screen reader," Brown notes. Adobe is working on reading software that would use more sophisticated logic in presenting information to an end user whose screen reader would automatically be detected. The software would then communicate directly with the end user via a dialogue box.

Brown and Hubbard are reluctant to discuss specifically when this software may be available from Adobe. Brown notes that customers prefer complete new programs in lieu of plug-ins and that the developmental cycle at Adobe is about 18–24 months. Furthermore, new software to enable authors to create accessible PDF forms is already in beta testing by some governmental agencies, Hubbard adds.

In addition, another Adobe plug-in product, Make Accessible, allows a text file to be created from a legacy PDF file by identifying structural intricacies that would stymie a screen reader, analogous to the way in which Bobby and similar testing tools identify inaccessibility features of a web site's design.

Current versions of PDF documents are supported by the latest versions of JAWS and Window-Eyes on systems using the latest version of Microsoft Active Accessibility. If you do not have a current version of either screen reader, you will not be able to read PDF files. Accessible forms will have to wait for a future generation of authoring and reading tools.

Freedom Scientific is offering a two-day course, Creating and Testing for Document Accessibility with HTML, Adobe and JAWS, at its St. Petersburg, Florida, corporate headquarters. The current version of JAWS has a utility that Kerscher, a long-time JAWS user, notes works well on simple documents but "fails horribly" on documents with margin notes, footnotes, and other complexities in structure.

Doug Geoffray, a principal of GW Micro, says that his company is working with Adobe on creating a way for end users to read forms with Window-Eyes yet maintain the secure, read-only status of these forms. He notes that Acrobat Reader 5.05 has smoothed out many of the glitches involved in using a screen reader to access PDF documents; the issue for Window-Eyes also remains with reading complex documents and forms.

A key component of the accessibility solution is the authoring tools—the software used to create the PDF document. Proper electronic tagging permits the reading software to make better guesses on layout and structure.

Section 508 does not apply retroactively; it covers only information created since June 2001, according to Doug Wakefield, chief architect of the 508 regulations and a senior technology specialist with the federal Access Board. "There's a lot of unreadable PDF out there. But I tell people that we didn't create these regs just for us; we created them for the generations coming after us." And, he notes, "the onus for accessibility is on the author of PDF documents."

Until authoring and reading tools of PDF catch up with each other—most authoring tools do not produce an accessible form of PDF—Kerscher recommends requesting documents in nonproprietary formats, such as XML or HTML, or in a more popular format, which is not guaranteed to be compatible across versions and platforms, such as Word. Referring to the source of the document, he advises, "Go upstream."

Meanwhile, as of this writing, Adobe is planning a workshop for the IRS in August to focus on design issues for accessible forms. AccessWorld will continue to cover developments on this critical access issue.

Requirements for Reading PDF

To read PDF files, you need Adobe Acrobat or Acrobat Reader version 5.0 or higher. The Acrobat Reader is available free of charge on Adobe's web site, <www.adobe.com>. When downloading, make sure you select the version that includes search and accessibility features. On this web site, there is additional information about URLs that will translate PDF documents into text format. You also need the correct version of either JAWS for Windows or Window-Eyes. Window-Eyes 4.1 or later supports Acrobat and Acrobat Reader 5.0, as do version 3.71 and later versions of JAWS for Windows.

When using either Window-Eyes or JAWS for Windows, reading an accessible PDF file is similar to reading a web page. PDF files can contain text, graphics, forms, and links. Both screen readers let you simply use the arrow keys to move within the document and give you the ability to get a list of links within a document. In PDF documents, links take you to another part of the same document. Form fields allow you to enter information into the document. Once this information is filled in, the PDF document can be printed using Acrobat Reader.

Resources

Acrobat 5.0 FAQ [Online]. Available: <http://access.adobe.com/accessibility.html>.

Acrobat 5.0.5 update FAQ [Online]. Available: <www.adobe.com/products/acrobat/pdfs/acr505faq.pdf >.

Sajka, J., & and Roeder, J. PDF and public documents: A white paper [Online]. Available: www.afb.org/info_document_view.asp?documentid=1706.

Staff. (2002, April 24). Making PDFs accessible: The big picture [Online]. Available: <www.pdfzone.com/news/101078.html>.

No title

September 18–20, 2002

International Conference on Disability, Virtual Reality, and Associated Technologies (ICDVRAT).

Veszprém, Hungary. The conference will address visual impairment.

Contact:

Professor Paul M. Sharkey, ICDVRAT 2002; phone: 011-44-118-931-67-04; e-mail: <p.m.sharkey@reading.ac.uk>.

October 3–5, 2002

World Congress and Exposition on Disabilities.

Orlando, FL.

Contact:

World Congress and Exposition on Disabilities; phone: 877-923-3976 or 201-226-1446; e-mail: <wcdinfo@wcdexpo.com>.

October 17–19, 2002

20th Annual Closing the Gap Conference on Computer Technology in Special Education and Rehabilitation.

Bloomington, MN.

Contact:

Closing the Gap; phone: 507-248-3294; e-mail: <info@closingthegap.com>; web site: <www.closingthegap.com/conf>.

October 29–November 1, 2002

SpeechTEK International Exposition and Educational Conference.

New York, NY.

Contact:

Chris Nolan, conference manager; phone: 877-993-9767 or 859-278- 2223; e-mail: <chris@amcommexpos.com>.

November 6–8, 2002

Fifth Annual Accessing Higher Ground: Assistive Technology in Higher Education.

Boulder, CO.

Contact:

Disability Services, University of Colorado; phone: 303-492-8671; e-mail: <dsinfo@spot.colorado.edu>; web site: <www.colorado.edu/sacs/disabilityservices/index.html>.

No title

The American Foundation for the Blind's National Technology Program began conducting product evaluations in 1987. In January 2000, AccessWorld became the home for our product evaluations. Last March, AFB opened the Technology and Employment Center at Huntington, West Virginia (AFB TECH). AccessWorld contributing editor Mark Uslan has relocated to Huntington and is the Managing Director there. Darren Burton has joined us as National Program Associate in Technology and will contribute to AccessWorld regularly. Two Marshall University students, Angie Spiker, a medical student at the Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, and Karla Schnell, a mathematics major in the College of Science, are AFB TECH product evaluation interns. AFB TECH will focus on evaluating the accessibility of mainstream products, and provide the resources for us to bring you articles on topics that we have never covered before.

This issue features the first example of AFB TECH's work. Mark Uslan, Angie Spiker, Karla Schnell, and Darren Burton evaluate blood glucose meters. They provide some background information on diabetes and on how meters work, review five off-the-shelf meters to identify those that have the most usable features for diabetics who are visually impaired, review meters that offer speech output capability, and show how blood glucose meters are being used by four blind and visually impaired individuals. Finally, Caesar Eghtesadi, Ph.D., president of Tech for All <www.tech-for-all.com>, an accessibility consulting firm, describes how technology for monitoring blood glucose levels will be changing in the coming years.

The June 2001 implementation of the requirements of Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act and the publication of a white paper calling attention to the accessibility issues involving Portable Document Format (PDF) files in April 2002, by AFB, partnering with National Industries for the Blind (NIB) and the American Council of the Blind (ACB), have raised the awareness of a greater need for accessibility by Adobe in the development of both its authoring tools and its reading tools. Annemarie Cooke, Senior External Relations Officer at Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, spoke to Adobe officials and leading accessibility advocates, and reports on the current state of PDF access, as well as what we can expect in the future. She also describes what you need to be able to read PDF documents with a screen reader.

Deborah Kendrick writes about video description—an additional audio track that describes the visual elements on the television or movie screen not readily detected in dialogue or other sounds. On April 1, 2002, new regulations from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regarding video description for blind television viewers became effective. Kendrick gives a brief history of video description and focuses on the necessary equipment and the steps you need to take to bring video description into your home.

James A. Kutsch, Jr., Ph.D., Vice President of Technology for a global leader in outsourced customer service and billing, provides an overview of audio on the web. He explains what you need to listen to audio, and describes several sites that will get you started with Internet radio. He discusses voice chat–speaking to a group of people over the Internet–which, unlike some text-based chat software, is accessible to screen reader users. Find out where to go to hear music and other programming that has disappeared from your AM/FM radio.

Dawn Suvino, Coordinator of Blindness and Low Vision Services at the Westchester Institute for Human Development in Valhalla, NY, and the Project Coordinator for a three-year research grant at AFB, reviews Adaptive Technologies for Learning and Work Environments, Second Edition, by Joseph J. Lazzaro. She found the book, available in print and on CD-ROM, to be "easy to read and understand, even for the most inexperienced user." The book describes standard computer hardware, input systems, products for use by people with vision, hearing, motor, speech or learning impairments, assistive technology evaluations, specialized training, technical support and funding options.

Jay Leventhal, Editor in Chief

No title

Screen Magnifiers with Speech

AiSquared recently released the newest version of its screen magnifier with speech, ZoomText 7.1. The 7.1 version features CompatibilityOne, which offers support for all Windows operating systems, including Windows XP, ME, 2000, NT 4.0, 98, and 95. ZoomText 7.1 includes IBM's ViaVoice speech synthesizer, which includes French, French Canadian, German, Italian, Spanish, Finnish, and Portugese. A command interface for Dragon Naturally Speaking Professional is also included so Naturally Speaking users can control ZoomText with voice commands. The new version of ZoomText is designed to magnify, track, and speak Java applications that are compatible with Java Access Bridge. The cost of ZoomText 7.1 ranges from $395 to $595, and upgrades range from $50 to $195. For more information, contact: AiSquared; phone: 802-362-3612; fax: 802-362-1670; e-mail: <sales@aisquared.com>.

MAGic 8.0 is the new release of Freedom Scientific's screen magnifier with speech. The new version supports Windows XP Home or Professional versions and an English download is currently available at <www.freedomscientific.com/fs_downloads/magic.asp> for authorized users. The MAGic 8.0 software is designed to magnify information on a computer screen, from two to 16 times its normal size. MAGic 8.0 is designed to communicate directly with JAWS for Windows version 3.71 or higher, making user intervention unnecessary. New features of version 8.0 include: a talking, large-print installation wizard; a new user interface with color-coded buttons and menus; a MAGic Key feature, which is designed to simplify hot key functions; and advanced navigation and view options. A version of MAGic 8.0 without speech is also available. Prices for MAGic 8.0 range from $595 to $295. For more information, contact: Freedom Scientific; phone: 800-444-4443 or 727-803-8000; e-mail: <info@freedomscientific.com>.

Ergonomic CCTV Magnifier

ERGO is a closed-circuit television (CCTV) reading machine that is designed ergonomically so that it may be adjusted for safe, efficient use by people with a variety of needs. The CCTV features magnification of 1.7-71X, a reading table that can be moved in four directions, and an adjustable monitor stand. The CCTV comes with a color or black-and-white monitor in rolling-stand or table-top models. ERGO is manufactured by Rehan Electronics and is distributed in the United States by Access Ingenuity. The ERGO with color monitor costs $2,995; the black-and-white version costs $2,295. For more information, contact: Access Ingenuity, 3635 Montgomery Dr., Santa Rosa, CA 95405; phone 877-579-4380; fax: 707-579-4273; e-mail: <access@accessingenuity.com>; web site: <www.accessingenuity.com>.

Computer Combined with a Note-Taker

Beyond Sight recently released Visionary LapTalk, a screenless laptop computer with an integrated text-to-speech application. LapTalk operates in a purely Windows environment and has 256 megabytes of RAM and 20 gigabytes of storage, compared to an average notetaker's 16 megabytes of memory shared between RAM and storage. The computer is equipped with a Window-Eyes screen reader, Windows XP, a modem and network port, Internet Explorer, Outlook Express, and word processing, spreadsheet, and database applications. LapTalk weighs 2.6 pounds and is 11 in × 9 in × 1 in. Visionary DeskTalk is the nonportable version of LapTalk. The price for LapTalk is $1,995; DeskTalk costs $1,095. For more information, contact: Beyond Sight; phone: 303-795-6455; e-mail: <bsistore@beyondsight.com>; web site: <www.beyondsight.com/laptalk_&_desktalk.htm>.

Assistive Technology Training Materials

De Witt and Associates, a New Jersey-based training firm that specializes in the use of computers and assistive technology for people who are blind or visually impaired, has developed a series of training tools for teaching Microsoft Office applications using JAWS for Windows, Window-Eyes, ZoomText, and MAGic. Courseware For Assistive Technology Trainers is designed to provide tools for training people how to use assistive technology. Course materials are currently available for the following applications: Microsoft Word, Excel, Internet Explorer, Outlook Express, and Windows Concepts. Course materials for PowerPoint and IBM's Home Page Reader will be available in the future. Each set of materials contains: lesson objectives and instructor's notes; a list of key terms and keystrokes; a step-by-step lesson plan; and assessment tools. The course materials include a print manual, an MS Word-formatted manual, and a CD-ROM that provides access to a trainer's web site for updates, tips from the field, and other comments or suggestions. For more information, contact: De Witt and Associates; phone: 877-447-6500 or 201-447-6500; e-mail: <sbb32@dewittassociates.net>.

Adaptive Technologies for Learning and Work Environments (2nd ed.), by Joseph J. Lazzaro

Washington, DC: American Library Association.web site: <www.ala.org>. $48 print, $35 CD-ROM.

This book offers readers a comprehensive overview of the myriad assistive technologies (ATs) that are available to persons with sensory, physical, and cognitive impairments. The book, which is available in print or on CD-ROM, is easy to read and understand, even for the most inexperienced user. The CD-ROM version uses a weblike design that is straightforward and logical. Hyperlinks in the text let readers move quickly from one chapter to the next, jump to an associated appendix, or return to the contents. Although the text is sometimes marred by sloppy proofreading, broken links and mislabeled headings, most readers will find the CD-ROM highly accessible.

The book begins, in Chapter 1, with a clear and concise description of the standard components of computer hardware. Readers learn, in simple terms, about processors, clock speed, memory, and disk storage capacity. While technically savvy readers may find some of the chapter's simplified language misleading (e.g., the author's definitions of kilobytes and megabytes are, by his own admission, not entirely accurate, and his discussion of "scan-and-read" technology leaves much to be desired), Lazzaro directs the experienced computer user to bypass Chapter 1 altogether. Still, this chapter gives readers a solid foundation for comprehending the rest of the book.

Although an introductory disclaimer states that the book focuses primarily on Microsoft Windows as today's dominant operating system, Chapter 1 includes an overview of the Apple Macintosh and Unix. In addition, the author provides readers with some equally useful (if now only narrowly applicable) information related to DOS.

In the section, "Selecting a Personal Computer," Lazzaro gives readers with disabilities some excellent advice: First determine (with or without the aid of an AT specialist) which adaptive devices you will use and the specific system requirements for those devices. He could have added a caveat that manufacturers' guidelines are sometimes less than fully accurate; as experienced users know, often the minimum recommended specifications are barely sufficient to the AT user's needs. Generally speaking, the latter sections of Chapter 1 are replete with useful advice for the user with disabilities who is preparing to buy his or her first computer; for example, purchasing all your equipment from a local dealer who has expertise in AT installation can be especially helpful if you don't have (or do not wish to acquire) high-level technical configuration skills. Similarly, Lazzaro urges new users to seek informal consultation, technical guidance, and support from disabled peers and to experiment with demonstration versions of popular products whenever possible. He returns to and even underscores some of these important points later in the book in discussing the role of an AT evaluation, specialized training, and technical support.

Chapter 2 is dedicated to a thorough exploration of input systems, with particular emphasis on keyboard access. Again focusing primarily on Microsoft Windows, Lazzaro describes standard keyboard commands and cross-application consistency. Readers learn how to navigate the Graphical User Interface and identify and interact with common screen objects, such as menus and dialogue box controls. Concepts and keystrokes related to multitasking and selecting text are also presented. Because Lazzaro describes keyboard access as a kind of built-in accessibility option, it is fitting that Chapter 2 also includes an overview of the Windows Control Panel and accessibility utilities, like Sticky Keys, High-Contrast Settings, Narrator, and Magnifier. As is the case with most of the book, the Apple Macintosh and Unix get little more than an "honorable mention" here.

Chapters 3–7 describe systems and software that may be particularly helpful to users with vision, hearing, motor, speech, and learning impairments, respectively. Perhaps some of the book's most insightful comments are found in the discussions of products that, while designed for use by one group of disabled users, may be equally applicable to another. The chapter on learning disabilities is especially illustrative of this fact, in that Lazzaro explains, for example, that screen readers and optical character recognition systems, originally developed for blind users, are of great use to users with learning disabilities as well. Similarly, word prediction and abbreviation expansion software may be widely applicable to users with vision, motor, or learning disabilities. There is, however, a glaring omission: users with multiple sensory, physical, and/or cognitive impairments. Because Lazzaro's book attempts at least to touch on all the ATs used by disabled persons, it is unfortunate that the author, like so many others in the field, avoids the topic of multiple impairments. Lazzaro flirts with the idea of multiple impairment and accommodation by cautioning users against purchasing any software or add-ons without first testing them with a third-party AT, but, again, a more complete discussion of the technical compatibility and usability issues surrounding the use of complex, multimodal AT configurations would have represented an important and unique contribution to the field. One can only hope that the topic may find its way into the third edition of this otherwise seminal work.

The last three chapters of the book (8, 9, and 10) do not deal with technology per se, but, rather, focus on AT evaluation, specialized training, technical support, and funding options. Chapter 8, "Foundations for Assistive Technology," stresses the importance of having a qualified AT specialist conduct a task-specific evaluation before you purchase a system configuration.

In Chapter 9, Lazzaro examines the Internet as a rich source of training materials, peer support, and technical assistance. He explains that users with disabilities can and should look to various online resources for ongoing support, even after the appropriate AT systems have been deployed. Unfortunately, neither Chapters 8 nor 9 link to appendices of relevant resources, as do virtually all the preceding chapters. Nevertheless, the astute reader will be able to locate qualified AT evaluators and appropriate training venues by carefully reading through the lists of national resources catalogued in appendices H–M.

Chapter 10 deals with potential funding sources to which individuals can look for assistance with the acquisition of, training in, and technical support for equipment. Although Lazzaro spends a fair bit of time discussing personal loans and revolving credit, the chapter includes some useful tips for users who do not wish to or are unable to avail themselves of the options offered by commercial lending institutions. Indeed, he might have remembered the critical role that the AT specialist can play in making cost-effective recommendations. Instead, he offers advice that is sometimes severely oversimplified (e.g., since hardware-based ATs are generally more costly than software solutions, it is best to select software solutions, whenever possible). Again, users would be well advised to heed Lazzaro's earlier suggestion by properly investing in an individualized, task-specific AT evaluation when they select a system configuration. Efforts to reduce cost can and should be guided by an AT specialist, whose knowledge and expertise will help the new user determine which devices are essential and which are not. As Lazzaro indicates, users must learn to distinguish between their "dream" systems and those components that are of primary importance. By using this book and the multitude of resources cited throughout the text and in the appendices, even the most inexperienced computer user will be able to start making those determinations independently.

Now Playing on Your Computer

There's no doubt that a personal computer (PC) with an Internet connection is a powerful tool for everyone, but it is especially powerful for visually impaired individuals. Much like the ways that sighted people use electric lights or reading glasses to do many different things, the Internet-connected PC is an interface to a wide range of activities. With a computer and a good screen reader or screen magnifier, you can read a newspaper, correspond with friends, check the weather, find out what's on TV, balance your bank statement, pay bills, browse a catalog, order products and services, trade stocks, research and plan a vacation, purchase travel or entertainment tickets, follow sports teams and game scores, research topics for school or personal development, play games, and more.

Sometimes other family members view using a PC as a single activity and make statements like "Are you still on that computer?" With a deeper understanding of the PC as a portal to facilitate all the different activities just enumerated, the question seems equivalent to asking a sighted person "Are you still using that lightbulb?"

The first part of this article dives right into Internet radio and voice chat. These sections are enough to get you started enjoying this entertainment source. Toward the end, some definitions are given for readers who want to understand how it all works.

Start the Music

To play web audio sources, you need a player—software that transfers the audio material to your sound card. Several different players are available free for download. Each has different features and devoted fans who tout its advantages over another. In fact, several web sites and mailing lists are devoted to specific player packages. Although some players can play proprietary audio formats exclusive to them, most will play several of the more common formats. Therefore, when getting started in web audio, you can pick essentially any one and later try others until you discover your favorite.

The more recent Microsoft operating systems come with Windows Media Player already installed. Another player that is popular with screen-reader users is Winamp from Nullsoft, a freeware package. You can learn more about Winamp at <www.winamp.com>. Configuration files for both JAWS for Windows and Window-Eyes are available for Winamp. You can learn about various versions of RealNetworks' RealPlayer, some free and some requiring a license fee, at <www.real.com>. A convenient and accessible place to obtain any of this software is from the download link on ACB Radio's main page at <www.acbradio.org>. This download page contains links to download any of the players just mentioned, along with the corresponding screen-reader configuration files.

Tune In

One fascinating development on the Internet has been the proliferation of web broadcasting. Web broadcasting allows a radio station's programming to be sent over the Internet as a series of IP (Internet Protocol) packets that contain digital audio. The term streaming audio is used to describe this technology. Digital signal processing (DSP) techniques are used to encode and compress the audio into a format that requires a fairly narrow bandwidth. A high-quality stereo program can be sent over a 28.8 Kbps dial-up Internet connection and still leave enough bandwidth available for e-mail or web surfing. Without compression, most Internet users could not listen to audio in real time. Other than the inconvenience of waiting, it really doesn't matter how long it takes to download a file to disk. But with streaming audio, one minute's worth of digital audio data must be transferred in one minute or less, or else there will be gaps or pauses in the audio while the computer waits for more data to arrive. These pauses significantly reduce the quality of the listening experience.

Many commercial, on-the-air radio stations offer Internet streaming audio access to their programs. Check your favorite radio station's home page, and you may find that you can listen to the station's broadcasts online. A good place to find radio stations is the radio station locator page at <www.radio-locator.com>. This site, previously known as the MIT list of radio stations on the Internet, includes an excellent search by call letters, city, or type of program. It lists all the radio stations, but indicates "BC" for those that offer bitcasting of their programs via the Internet. Clicking on the BC link next to these stations will bring up your default player and start the stream.

In addition to listening to on-the-air radio stations, there are many Internet-only broadcast streams to explore. The American Council of the Blind sponsors four channels of programming on ACB Radio. Go to <www.acbradio.org> to get started. There, you will find links to MainStream, featuring news, talk, and current events; the Café, showcasing the music of blind artists; Treasure Trove, a collection of old-time radio dramas; and ACB Radio Interactive, featuring live disk-jockey programs with listeners' requests. All these streams are available 24 hours a day. A program guide, as well as archives of prior content, are also provided on the site.

Time for Your Own Show

Anyone can start web broadcasting. Unlike commercial radio stations that require costly equipment and a license to operate, web broadcasting is open to all. There are no license requirements, and the typical home computer is sufficient to run the needed software. The ACB Radio Interactive channel features a collection of individuals who are interested in producing radio programs. The ACB Radio site has a section describing the necessary software and even offers a support group of others who will help you get started. This is a fine place to start, since their broadcasters are experienced users of the software with screen readers.

For a more general list of individual Internet broadcast programming, check out <www.live365.com>. There, you will find an extensive list of Internet broadcast streams. If that's not enough to fill all your listening hours, go to your favorite search engine and search for various terms, such as Internet broadcasting or Internet radio.

Let's Talk

The ultimate use of streaming audio is in voice-chat rooms. Conceptually, voice chat is similar to text chat using IRC or MSN Messenger, except that your voice, rather than your keystrokes, is sent to the other parties. Voice chat can be conducted using Microsoft's NetMeeting, as a part of the overall collaboration services offered by that software. However, for easy access to other participants who are interested in chatting, there are alternatives. Two sites that provide this service to many Internet users who are visually impaired are <www.audio-tips.com> and <www.for-the-people.com>.

To use the Audio-tips or For-the-People voice-chat services, you need a microphone and chat software. Many laptops have built-in microphones, and some newer desktop systems include them with the modem packages. If your PC doesn't have a microphone, you can get one at your local computer store or Radio Shack for under $20. Many people prefer a boom microphone built into headphones. As for the software, a small browser plug-in is downloaded to your PC. This software performs digitization and compression of your voice via a microphone plugged into your sound card. It also decompresses and decodes the received audio from other chat-room participants. The techniques are the same as those used in digitized streaming of audio in web broadcasting.

George Buys, the creator of Audio-tips, has established a free place for people to meet and chat on a variety of topics. His site includes a collection of chat rooms designated for various topics. On your first visit, you need to register and accept the automatic download of the plug-in software. Then you can enter any room and talk with other users of the site from around the world. There is a convenient conversation-locator frame on the main page, so you can tell who is currently in each chat room. If you come to the site at a time when no one is there, you should enter a room of interest anyway and wait. Once you have entered a room, your screen name will appear in the locator frame. As others notice that you are there, they can join the room to chat. Sometimes you may have a conversation with only one or two others, and sometimes as many as 15 or more people may be in the chat room at the same time.

Several organized discussions and training seminars take place on the Audio-tips site. These events are listed in a schedule that is posted on the site. Checking the schedule of events can help you find information about upcoming hosted discussions on specific topics of interest to you. But you aren't limited to existing events. Not only can you chat about anything of interest in the open rooms, but you can offer to host a special or recurring discussion on the site.

If you prefer more proactive notification of upcoming events, there is a mailing list to which you can subscribe. Subscribers receive periodic announcements of upcoming events and continue building relationships with other users. The sense of community among Audio-tips users is one of George Buys' greatest accomplishments with the site.

The For-the-People voice-chat site offers free voice-chat services similar to Audio-tips. As is true with local coffee shops or pubs, each of the two sites has regulars who frequent the chat rooms. Try them both and decide for yourself where you want to spend your voice-chat time.

What's Behind the Smoke and Mirrors?

Digital audio has been around for years. Compact disks (CDs) are the dominant medium for music. These CDs store one form of digitized audio. Other digital audio formats include the wave files found with the extension ".wav" on your PC and MP3 files found on computers and portable digital audio players. The name MP3 is short for MPEG Audio Layer 3, an international standard for a digital audio format. MPEG stands for Motion Picture Experts Group, which set the original audio/video standard.

The original source material is typically an analog audio source. Here, analog refers to the fact that the sound wave covers a continuous range, rather than a set of discrete numeric values. To illustrate, your height is an analog value, but when it is measured in whole inches, the fine details of any fraction of an inch are lost in the whole-number, digital representation.

The analog audio is a waveform. To understand, think of waves on the ocean. Two elements are important: the height of the wave, called amplitude, and the number of waves that pass by over a certain period, called frequency. The height of the wave is dependant on the volume of the sound. The frequency, the number of waves that pass by each second, is determined by the pitch of the sound. This analog waveform eventually drives a speaker or headphone. The frequency of the electronic analog waveform causes the internal surface of the speaker or headphone to move in and out at a particular speed, generating a specific sound pitch. Higher frequency means more rapid movement and thus a higher pitch. The amplitude of the electronic analog wave controls how far the speaker surface moves in and out with each wave and thus controls the volume of the sound. Higher amplitude means more speaker movement, which means louder sound.

Is There More?

If you want to dive deeper, check out the resources listed at the end of this article. If these are not enough, there are mailing lists covering a range of PC audio topics described further on the Winamp-for-the-blind web page. One informative list devoted to digital music issues for blind individuals is PC-audio. You can subscribe by sending an e-mail message to <pc-audio-subscribe@yahoogroups.com>.

Resources

Speak Freely, an Internet-to-Internet PC phone package. Visit <www.acbradio.org/download.html> for links to the software and tutorial information.

CD Ripping, extracting the audio from a CD into PC audio files. Visit <www.poikosoft.com> for a shareware package called Easy CD DA Extractor.

Winamp, one of the players mentioned earlier. Visit <www.shannon.reece.net/Winamp4TheBlind.html> for tips and some interesting Winamp plug-ins.

Whatâs on Tonight?

I had only one blind friend while I was growing up. She lived across town and went to another school, so what little time we had together was treasured, indeed. One summer night stands out in my memory. We spent the evening in a sleepover, as most teenage girls do: eating popcorn, drinking lemonade, giggling, and watching late-night TV in her parents' living room.

A 1942 movie was on around midnight, and about halfway through it, we became interested. It was the romantic part that captured us—the tough guy, wildly in love with the woman from his past, now married to someone else. Suddenly, in the penultimate scene, there was more music than dialogue, and we were stuck. Did she get on the plane or not? The answer meant everything to the romance of the thing, and the dialogue was enigmatic.

"What happened?" we asked one another simultaneously, and then began to giggle when we realized that neither of us could tell the other the answer. We were laughing, but there was a certain poignancy in that moment, too, a moment that I now know was a reminder to each of us, silently, that we were excluded.

Movies and TV programs have become even more sophisticated (and visual) over the decades. Scenes change rapidly. Images are superimposed over one another. Animation is artfully blended with real life. To appreciate the medium on a par with viewers who have both sight and hearing requires access to both audio and video elements. Whether TV is a priority in your life or not, it is a significant part of our culture. At the office, the gym, the school playground, or family picnics, TV programs and movies come up in conversations. For those who want to take part in those conversations and who happen to be blind, the possibilities for accessible TV viewing have increased significantly in recent months.

A Bit of History

With the launch of Descriptive Video Service (DVS) by WGBH-TV of Boston in the late 1980s, some TV programs began carrying an additional audio track, concisely describing the visual elements on the screen that could not be readily detected in dialogue or other sounds. There were only a few programs at first, but the number and variety of programs with description has grown steadily—as has the number of Public Broadcasting System (PBS) stations around the country broadcasting the DVS track when it is available. DVS became a permanent national service in 1990, broadcasting American Playhouse with description to 32 PBS affiliates. By 1997, the number of stations that carried DVS had grown to 144, and DVS was available in the top 20 TV markets and 78 percent of U.S. households. Today, WGBH provides approximately 10 hours of described programming each week, including such popular programs as Nova, Nature, American Experience, and Masterpiece Theatre, for adults; and such children's favorites as Arthur, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, and Zoom.

It is no surprise that WGBH has been a pioneer in providing access to the visual elements of TV for those who are unable to see the screen. A decade earlier, this station gave birth to the concept of closed captioning—presenting on-screen text equivalents of spoken dialogue and sounds for deaf viewers. It is now rare to find a TV program without captioning on any network, and, as so often happens with innovations initiated for people with disabilities, captioning is enjoyed by many who are not hearing impaired.

In 1996, Turner Classic Movies (TCM) began offering movies on Sunday evenings with description. To date, TCM has added description to approximately 150 classic movies and broadcasts the accompanying description whenever those movies are aired. Films offered include such perennial favorites as Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, National Velvet, Citizen Kane, The Sunshine Boys, and Pride andPrejudice.

Gaining Prime Time

If your TV tastes run elsewhere than to public TV or classic movies, read on. On April 1, 2002, a new FCC rule took effect that will dramatically increase the amount of described programming now available. The new rule requires the four commercial networks (ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC) to add description to at least 50 hours of programming per calendar quarter (about four hours a week), with priority given to prime-time and children's programs. At this point, the only stations that are required to pass through the described broadcasts are those in the top 25 markets (see list of cities at the end of the article) or those that can easily do so (if, for instance, a station in a smaller market already owns the necessary equipment). Popular programs already appearing with description on these networks include CSI, The Simpsons, Blue's Clues, and Bernie Mac (see the list of more programs at the end of the article).

The new rule places the same requirements on distributors of Multi-channel Video programming with at least 50,000 subscribers. Networks (in addition to TCM) on cable and satellite systems that have begun to carry video description include Lifetime, USA, TNT, and Nickelodeon.

Getting with the Program

Now comes the hard part. Putting programs with description on the air is one thing, but it takes a certain amount of technological savvy to bring those programs into your living room.