Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Full Issue: AccessWorld March 2002

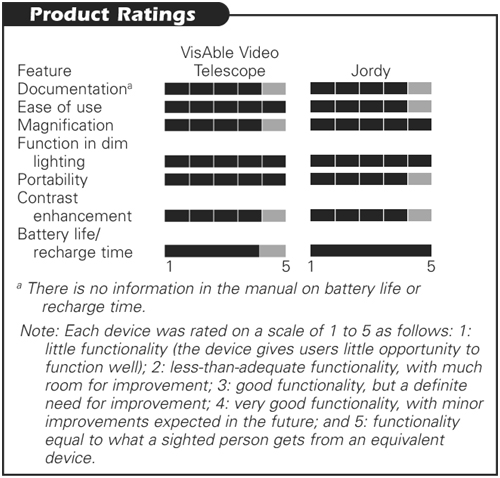

Product Ratings

Product Ratings

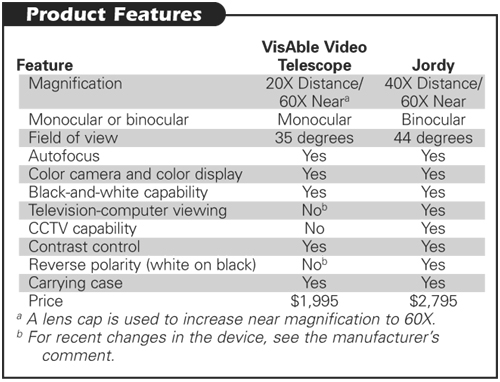

Product Features

aA lens cap is used to increase near magnification to 60X.

bFor recent changes in the device, see the manufacturer's comment.

VisAble Video Telescope

Magnification: 20X Distance/60X Neara, Monocular or binocular: Monocular, Field of view: 35 degrees, Autofocus: Yes, Color camera and color display: Yes, Black-and-white capability: Yes, Television-computer viewing: Nob, CCTV capability: No, Contrast control: Yes, Reverse polarity (white on black): Nob, Carrying case: Yes, Price: $1,995.

Jordy

Magnification: 40X Distance/60X Near, Monocular or binocular: Binocular, Field of view: 44 degrees, Autofocus: Yes, Color camera and color display: Yes, Black-and-white capability: Yes, Television-computer viewing: Yes, CCTV capability: Yes, Contrast control: Yes, Reverse polarity (white on black): Yes, Carrying case: Yes, Price: $2,795.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Features

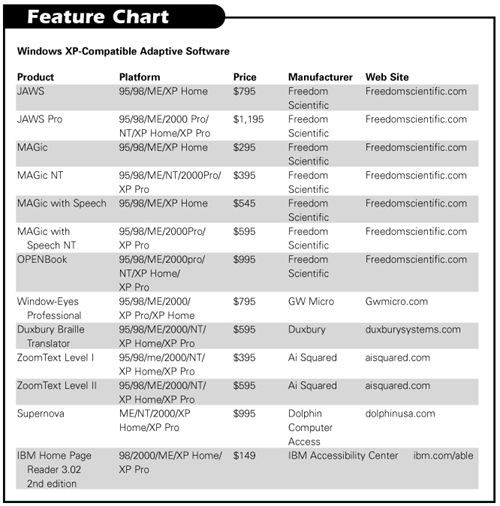

Feature Chart

Windows XP-Compatible Adaptive Software

JAWS Platform: 95/98/ME/XP Home Price: $795 Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Web Site: <Freedomscientific.com>, JAWS Pro Platform: 95/98/ME/2000 Pro/NT/XP Home/XP Pro Price: $1,195 Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Web Site: <Freedomscientific.com>, MAGic Platform: 95/98/ME/XP Home Price: $295 Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Web Site: <Freedomscientific.com>, MAGic NT Platform: 95/98/ME/NT/2000Pro/XP Pro Price: $395 Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Web Site: <Freedomscientific.com>, MAGic with Speech Platform: 95/98/ME/XP Home Price: $545 Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Web Site: <Freedomscientific.com>, MAGic with Speech NT Platform: 95/98/ME/2000Pro/XP Pro Price: $595 Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Web Site: <Freedomscientific.com>, OPENBook Platform: 95/98/ME/2000pro/NT/XP Home/XP Pro Price: $995 Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific Web Site: <Freedomscientific.com>, Window-Eyes Professional Platform: 95/98/ME/2000/XP Pro/XP Home Price: $795 Manufacturer: GW Micro Web Site: <Gwmicro.com>, Duxbury Braille Translator Platform: 95/98/ME/2000/NT/XP Home/XP Pro Price: $595 Manufacturer: Duxbury Web Site: <duxburysystems.com>, ZoomText Level I Platform: 95/98/me/2000/NT/XP Home/XP Pro Price: $395 Manufacturer: Ai Squared Web Site: <aisquared.com>, ZoomText Level II Platform: 95/98/ME/2000/NT/XP Home/XP Pro Price: $595 Manufacturer: Ai Squared Web Site: <aisquared.com>, Supernova Platform: ME/NT/2000/XP Home/XP Pro Price: $995 Manufacturer: Dolphin Computer Access Web Site: <dolphinusa.com>, IBM Home Page Reader 3.02 2nd edition Platform: 98/2000/ME/XP Home/XP Pro Price: $149 Manufacturer: IBM Accessibility Center Web Site: <ibm.com/able>.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Features

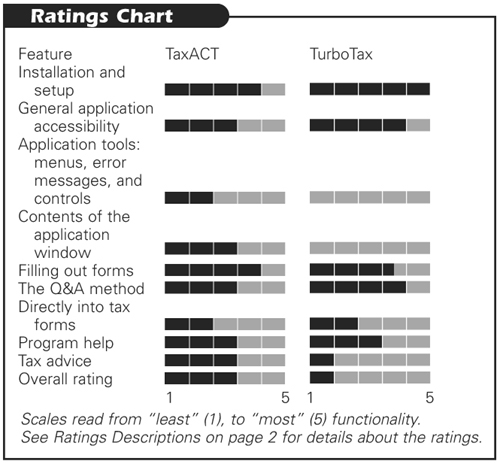

Ratings Chart

TaxACT

Installation and setup: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, General application accessibility: 3. Good functionality but a definite need for improvement, Application tools: menus, error messages, and controls: 2. Less than adequate functionality, with much room for improvement, Contents of the application window: 3. Good functionality but a definite need for improvement, Filling out forms : 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, The Q&A method: 3. Good functionality but a definite need for improvement, Directly into tax forms: 2. Less than adequate functionality, with much room for improvement, Program help: 3. Good functionality but a definite need for improvement, Tax advice: 3. Good functionality but a definite need for improvement, Overall rating: 3. Good functionality but a definite need for improvement.

TurboTax

Installation and setup: 5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device, General application accessibility: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Application tools: menus, error messages, and controls: NA, Contents of the application window: NA, Filling out forms : 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future./5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device, The Q&A method: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Directly into tax forms: 2. Less than adequate functionality, with much room for improvement, Program help: 3. Good functionality but a definite need for improvement, Tax advice: 1. Little functionality; the device gives users little opportunity to function well, Overall rating: 1. Little functionality; the device gives users little opportunity to function well.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Ratings

Note: Each device was rated on a scale of 1 to 5 as follows: 1: little functionality (the device gives users little opportunity to function well); 2: less-than-adequate functionality, with much room for improvement; 3: good functionality, but a definite need for improvement; 4: very good functionality, with minor improvements expected in the future; and 5: functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device.

aThere is no information in the manual on battery life or recharge time.

VisAble Video Telescope

Documentationa: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Ease of use: 5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device, Magnification: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Function in dim lighting: 5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device, Portability: 5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device, Contrast enhancement: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Battery life/recharge time: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future.

Jordy

Documentationa: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Ease of use: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Magnification: 5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device, Function in dim lighting: 5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device, Portability: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Contrast enhancement: 4. Very good functionality with minor improvements expected in the future, Battery life/recharge time: 5. Functionality equal to what a sighted person gets from an equivalent device.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Taxing Both Income and Patience: Reviews of TaxACT and TurboTax

Tax software holds the promise for blind taxpayers of independently calculating deductions, deciding whether to itemize, deciding whether to file jointly with your spouse or separately, and much more. This article reviews the accessibility of two commercial tax preparation packages: 2nd Story Software's TaxACT Deluxe and Intuit's Quicken TurboTax Deluxe. Versions for preparing 2001 federal taxes were not finalized at the time of the review, but both promised no real interface changes. The state tax forms were not available at the time of this review, but both packages promise direct importing of information into state forms, and there is no reason to expect accessibility to differ from program to program.

A 300 MHz Pentium laptop computer with 128 MB of RAM running Windows 98 was used. The computer's display was set to 256 colors, 800 x 600 resolution, and the display color scheme was set to Windows Standard. JAWS for Windows (JFW) 3.7 and Window-Eyes 4.1 were used for the review.

To use either tax program, you must know your screen reader, including its mouse-movement commands. Although some screen-reader configuration was helpful, in most cases, the configuration necessary was beyond the average user.

The following features were examined: installation and setup; general application accessibility (using standard Windows keystrokes or, at least, the mouse pointer); the application tools: menus, error messages, and controls; the application window (Is it displaying informational content, program instructions, and so forth?); filling out forms; program help; and tax advice. Some were divided into subcategories to represent dramatic differences in the accessibility of two parts of the same feature. In Product Ratings at the end of this article, an overall rating is given that is not the sum of the ratings for each factor but, rather, a reflection of the program's overall accessibility. Poor access made some features cumbersome and others not worth using at all.

This review is applicable to users of all screen readers, since the access issues were fairly consistent, regardless of the screen reader that was used. Performance varied significantly because of one factor: JFW comes with a script (configuration file) written for an earlier version of TaxACT. As a result, Window-Eyes worked a little better with no configuration files. But by renaming the JFW TaxACT 99 files to TaxACT01, the program was much more accessible using JFW. Some instructions for renaming these files are available upon request. The ratings reflect the accessibility of the tax software, not the availability of an old configuration file for one of the programs. Users of up-to-date versions of JFW should read the comments carefully because the ratings for that program are often lower than the actual performance they can expect.

TaxACT Deluxe

Installation and Setup

The TaxACT Download was basically accessible. The log-in link was not given a text label, although the file name connected with the link—"s_TaxACT/login"—was understandable. The setup was also basically accessible.

General Application Accessibility

Application Tools: Menus, Error Messages, and Controls

Both screen readers were successful at reading the actual TaxACT menus, but the items on the menu bar were spoken only by Window-Eyes. This was most likely a JFW problem, since Window-Eyes had no trouble. However, access to the menu bar was inconsistent. There seemed no pattern to the times when pressing the Alt key would put the focus on the menu bar and when it would do nothing. This problem occurred with both screen readers. It was usually possible at these times to press Alt+F (or any other menu shortcut) to bring down one menu, press Escape, and have the focus left on the menu bar. But sometimes even this procedure didn't work, and it was necessary to use the mouse to pull down a menu.

Most of the tool bar buttons have equivalents on the menus except for the Forward and Back buttons, which were often useful. These buttons need to be accessed using the mouse pointer.

Error messages in dialog boxes were fully accessible. However, error messages related to the forms themselves were displayed somewhere near the relevant form field. They were spoken consistently only by setting the screen reader to echo everything (Insert-S in JFW, Insert-A in Window-Eyes). This is a mediocre solution.

The Application Window

The seven buttons on the main screen represent seven steps to using the program. These buttons are nonstandard and are thus not spoken. All but the first, Basic Information, have menu equivalents, although it is not always clear which menu item equals which step (for example, the Review Return step is the Alerts option on one of the menus). The menu for the state return is arranged in a nice step-by-step order, making the omission of such an order in the federal return menu seem like an unfortunate oversight. Unfortunately, these unspoken buttons provide immediate instructions on how to start using the program. So, these nicely laid-out steps are available only to the blind user who thinks to look for Program Help in the Help menu.

Filling Out Forms

The basic forms were completed fairly easily. A return for a fictional character with a few complexities in his life was completed in a couple of hours. Since the layouts of the basic forms were fairly consistent, the process went faster after I worked out the initial problems. You can switch back and forth between two methods for completing the forms.

One method is a question-and-answer (Q&A) format in which each screen covers a different subject area (name, address, marital status, and so on). The other involves filling out forms that resemble the appearance of the print forms.

The Q&A process was somewhat usable. The opening screen offers standard edit boxes to fill in first name, middle initial, and last name. Tabbing past these boxes, you encounter the Continue button, which takes you to the next question, the Tax Advisor button, with answers to questions like "my name has changed since last year," and the Supporting Details button, which produces the same table whether or not it is relevant to the current screen.

If you have the JFW script, the field names for the edit boxes are read as you tab through them, and the buttons are spoken after a slight pause. Window-Eyes spoke the field names by reading the current line or routing the mouse pointer to the control and then up from there but did not speak the buttons. Even though the buttons are usually in the same order, it was helpful to get the confirmation because occasionally there was something extra between the form fields and the buttons.

Some of the controls in this Q&A structure involve yes-no or multiple-choice questions, which are nonstandard radio buttons. You simply arrow to the selection you want (the options are spoken using either screen reader) and then tab off them. However, there is no feedback to let you double-check your choice. Similarly, checking a box works by pressing the spacebar, but, again, there is no straightforward way to double-check your answer. The Supporting Details button leads to an inaccessible table. You can tab through these fields and enter data, but they did not function like standard tables, and it was not possible to read the total that supposedly appears at the bottom. The controls to save or print these forms were also inaccessible.

The "standard print tax forms" are even less accessible. If you tab through a blank row, you can often hear the field names read, but once one item has been filled in, field names in the remainder of the row are not heard. One purpose for entering this layout of the form is that sometimes the choices you make that are not reviewable in the Q&A (like your filing status) show up in the form with an x before the desired choice, giving you the missing feedback. However, making the choices directly in this layout of the form can be tedious.

Program Help

The Help function leaves something to be desired. Pressing F1 brings up the first of a set of informative screens that need to be read using the mouse pointer. There is no keystroke navigation or context-sensitive help.

Tax Advice

The Tax Advice (F2) presents a table of contents composed of items linked to the related information, making it clear where to "click" to access the desired information. The search feature allows you to search either Program Help or the Tax Guide. The list of tax-related topics that can be searched is quite detailed.

Quicken TurboTax Deluxe Installation and Setup

The installation process was a pleasure. The initial dialog box asks if you want to install TurboTax; it does not launch the installation process automatically. This question makes it possible for you to choose what to do.

General Application Accessibility

Accessibility of the Application Tools: Menus, Error Messages, and Controls

The menu bar and menus read well with both screen readers. Error messages in dialog boxes were fully accessible. However, error messages related to the forms themselves were displayed somewhere near the relevant form field. They were spoken consistently only by setting the screen reader to echo everything. Since this setting causes other information to echo in a manner that makes it unclear where you are, this is only a mediocre solution at best.

The Application Window

The foregoing description of the accessible elements of this program is striking in comparison to the fact that none of the text in the main body of the application reads at all, except for the title and the bar of Help questions on the side. These questions give clues to what happens if you activate the Continue or Go Back buttons that are read by screen readers.

Filling Out Forms

The Q&A-style series of forms, referred to as the Interview, is hard to use because the main body of information is unreadable by screen readers. It is possible to guess what is being asked, sometimes, because the buttons are labeled Start New Return or Download Now and the Help on the side is related to what is being asked. Occasionally, there is an accessible screen, such as the one for filing status.

The "forms" are much more accessible than the Interview. The field names are mainly readable text, but there is no consistency to positioning—sometimes on the line with the form field, sometimes above it. In some cases, it was almost impossible to find the right information.

Program Help

Help leaves something to be desired. However, it has some interesting and useful features. The Help utility comes up in its own window. While pressing F1 rings up Tax Advice, it is possible from there to select Program Help from the file menu. Program Help can also be selected directly from the applications Help menu. Although the screens must be navigated using the mouse pointer, the focus is at the top of the useful Help window, making it easy to route the mouse pointer to the correct starting place. The first screen of Program Help is basically a Contents screen, so any option can be "clicked" on to access the desired information.

The Help utility also includes a bookmark menu. Selecting Add Bookmark adds the page you are on to that menu for easy retrieval. You can find the Search function from the Edit menu of the Help utility as well as separately from the main application Help menu. In general, the program Help screens give instructions that work for the keyboard user. There is a lot more reference to selecting from menus than clicking on buttons.

Tax Advice

When F1 is pressed during completion of tax forms, the information displayed in the Help utility begins with the section most relevant to the field being completed. There are also several different approaches to getting tax assistance from the same utility, some of which are more accessible than others.

The program CD contains 35 searchable publications. Unfortunately, the instructions for using these publications refer to a Contents button that could not be located during this review. The publications can be searched by keyword, however. The database does not include tables, sample fill-in forms, or appendixes that are in the hard-copy publications. For the blind tax filer, this is possibly a critical omission.

Other resources included with this program are the Money Magazine Income Tax Handbook, which also relies on the elusive Contents button, a tax Q&A prepared by Intuit in consultation with professional tax preparers that is difficult to navigate in general, and a video library that is somewhat usable. What you can't access is the information about who is giving you the clips of information. Also, all the little videos refer to an inaccessible More Info Button.

The Bottom Line

TaxACT is the clear choice. There were enough major access problems with TurboTax to render it basically useless. TaxACT, although it has flaws, is a program that could be used to calculate a tax return. Clearly TaxACT has even more potential if some changes were made, such as using standard Windows and controls.

A major drawback is that you cannot import information from other financial packages, such as Quicken or QuickBooks, into TaxACT, although the manufacturer hopes to add this capacity in the future. TurboTax seems to offer a wealth of information that could help someone with complex tax issues in an enjoyable and entertaining manner. If that information were usable, it might be worth the cost of the program.

All in all, the results of this review were disappointing, and the more accessible program still leaves much to be desired. It is hoped that in the future, for the blind taxpayer, filing tax returns won't be this cumbersome and the choices won't be so limited.

Product Information

TaxACT Deluxe

Manufacturer: 2nd Story Software phone: 800-573-4287 or 319-373-3600 web site: <www.TaxACT.com>. Price: $19.95 Includes state forms and one free electronic filing.

Quicken TurboTax Deluxe

Manufacturer: Intuit phone: 800-440-3279 or 650-944-6000 web site: <www.intuit.com>. Price: $39.95.

How to Choose the Right Instructor

The title access technology specialist has an aura of one who knows everything about every piece of hardware, every screen-reading package, every synthesizer, and every possible combination of them. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Access technology specialists, for the most part, specialize in a particular niche in which they feel adept and well qualified. Some are experts in software, while others are whizzes at hardware and compatibility issues. Therefore, it is important for students to be able to determine the skills of these specialists and choose one who can best help them meet their personal needs for computer training.

Through careful screening and creative problem solving, you can find a qualified instructor with the skills necessary to provide a solid foundation in the use of computer applications and screen-reading software. Although you can easily find credentials for plumbers, contractors, and vacuum repair personnel, it is not easy to verify the qualifications of someone who teaches people who are blind or visually impaired to use computers. There may be no documentation of an instructor's knowledge of a particular software package, but you can determine the exact nature of an instructor's capabilities through some artful interviewing skills.

The Initial Interview

Before you accept an individual as an instructor, it is wise to ask for an interview. Most instructors are more than happy to meet with prospective students because it gives them an opportunity to assess the students' needs and gives the students an opportunity to gauge their skills. It may seem as though the tables are being turned on the instructor—after all, who would "interview" an instructor? If a state rehabilitation agency or employer hires the instructor, surely he or she must be qualified to perform the required training. In reality, an employer or rehabilitation counselor may have less knowledge about computers than you do and is merely choosing from a list of those who have been "certified" by the state or a local agency to teach.

Therefore, it is up to you to assess the instructor by asking probing questions and determining if the answers indicate that he or she has the experience and ability to teach the necessary skills.

There are several things you should consider when assessing the skills of an access technology specialist:

- personality

- preparation

- teaching experience

- demonstrable skills

- references

Personality

It is important that your and the instructor's personalities are compatible. If the instructor seems overly somber or too congenial, has an impatient nature, or doesn't appear to be a skilled listener, these characteristics could lead to problems during training. Problems may arise during training that could try the best of relationships. So, it is best to get off to a strong start by carefully assessing the instructor's personality. Most assessments last a couple of hours, so it is relatively easy to determine the instructor's personality, as well as other aspects of his or her qualifications, such as the preparation he or she puts into the classes.

Preparation

Preparation for training is an integral part of any instructor's daily life. From creating a lesson plan to providing a basic outline of the course, it is important that an instructor be aware of a student's needs and be prepared to show a definitive plan for future lessons. If an instructor is vague about his or her plans for future lessons, this should be a red flag that something is amiss. Although some students may feel comfortable with the "teach as you go" philosophy, it may be important for beginners or those who need to learn a specific application to have some structured training goals. An instructor who is going to be teaching a specific application or group of applications should be able to offer a lesson plan with specific skills to be taught during each lesson.

If the instructor doesn't have a lesson plan, you should ask if he or she plans to create one. If the instructor is going to be providing training in the use of Microsoft's e-mail package Outlook, for example, there are logical steps and basic skills that are integral to any course on this dynamic software. In addition, you may want to learn some aspects of the application but have no need for others, or there is some aspect of the application that is not covered in the lesson plan but would be important for you to learn. The instructor should be flexible enough to adjust the plan to your personal or professional needs. If the instructor seems unwilling to alter the plan or teach the necessary skills, it may mean that he or she is not the right person for the job.

Teaching Experience

The next thing to ask about is the instructor's experience teaching particular applications. If an employer hires an instructor to teach a complicated bit of software, it can be reassuring to know that the instructor has encountered the software in the past and has successfully trained others in its use. You should not hesitate to inquire about the number of students the instructor has taught and even request contact information for students who have successfully completed the same course of study with the instructor.

Finally, you can ask the instructor to demonstrate his or her teaching style. Pick something simple that will allow you to assess the instructor's skill in conveying information and concepts. For example, the instructor should be willing to teach the use of the desktop or the text navigation keyboarding of Windows and reading commands of a screen reader. Listen carefully and observe the instructor's teaching style. Does the instructor provide spatial references to the elements of the desktop? If the sample lesson is in the use of keyboarding and screen reading, does he or she differentiate between Windows commands and screen-reader commands? Does he or she speak clearly and explain the concepts and keystrokes in a relaxed and comfortable manner? Do the practical skills offered encourage you to explore the skills on your own computer at home?

Pay attention to the instructor's style of teaching. The desktop and navigation of text and screen-reading commands are fundamental skills that should come easily to experienced access technology specialists. If the instructor frequently refers to notes and his or her style seems hesitant, then perhaps an interview with another instructor may be in order.

The Bottom Line

If an instructor meets the criteria—has a relaxed and confident manner when teaching, offers a lesson plan, and is willing to demonstrate his or her skills and provide references—perhaps he or she is one who can guide you toward a solid foundation in the skills necessary to compete effectively in the workplace and beyond. If you have any doubts and an employer or rehabilitation counselor is footing the bill for the training, it is time to have a frank discussion about the instructor's qualifications and problems encountered during the assessment.

Training in access technology comes at a premium price. Some instructors charge $60 to $70 per hour for their services. If you have any doubt about whether the quality of the training offered is worth the price, it is your right and responsibility to look elsewhere for training opportunities. With a computer and modem, the world is at the fingertips of every blind computer user. Perhaps the optimal training opportunity isn't at a rehabilitation facility or through the services of a private instructor. There are a multitude of training opportunities, both free and for a fee, on the Internet. You should pursue every avenue and speak to others who have had successful training experiences to find an instructor who can ensure that you receive a solid foundation in the skills necessary to achieve a successful future in the world of computing.

No title

In this issue Joe Lazzaro, of the Massachusetts Commission for the Blind and a freelance author, provides an introduction to Windows XP. At press time, AccessWorld learned of a problem in Microsoft Office XP. Graphics Device Interface (GDIPlus) is used in Office XP applications such as Word or PowerPoint to draw embedded graphics directly to the screen, bypassing screen magnifiers and screen readers. As a result, a screen magnifier cannot magnify or smooth the images of embedded graphics. Microsoft is working on the problem and expects to have an update that corrects it available on its web site by the time you read this.

Deborah Kendrick profiles three people working successfully in the customer service field. Each one uses a screen reader and a braille display on the job.

Lynn Zelvin evaluates tax preparation software. Her tests of 2nd Story Software's TaxACT Deluxe and Intuit's Quicken TurboTax Deluxe show that it takes a lot of skill and screen reader knowledge to complete a tax return.

Debbie Cook, Project Director of the Washington State Assistive Technology Alliance, reviews the Sanyo 4700 cell phone and finds it somewhat accessible to blind users. In January, we promised a more in-depth article on what specific cell phone manufacturers and service providers have to offer. Some of the interviews necessary to complete that article were difficult to arrange, so it will appear in the May issue.

Mark Uslan and Ike Presley, National Program Associate in Literacy at the American Foundation for the Blind, evaluate Betacom's VisAble VideoTelescope, Enhanced Vision Systems' Jordy, and Clarity Solutions' MobileMate. Find out which one of these products will make it easiest for you to enjoy museums, sporting events, and other things you like to do.

How do you choose an assistive technology instructor? Cathy Anne Murtha, California-based online access technology specialist, outlines some suggestions in this issue's Trainer's Corner.

The April AccessWorld Extra will include our coverage of the Technology for Persons with Disabilities conference sponsored by the Center on Disabilities, California State University, Northridge (CSUN.) It will also feature reader comments and questions, assistive technology news, and more.

Jay Leventhal, Editor in Chief

Portable Video Magnifiers in Museums

Using a video magnifier or a closed circuit television (CCTV) in a classroom for both close-up work, such as reading a textbook, and distance viewing, such as reading the chalkboard, has appealed to teachers and students since the first CCTV system was introduced in the early 1970s. Until recently, video magnifiers that could be used in the classroom were heavy and bulky, required an electrical outlet, and were expensive. Today, they come in many different shapes, forms, and price ranges. The most popular ones are still the traditional desktop systems, which come with a movable x-y table for reading and use either a video monitor, television set, or computer monitor as a display. But things are changing.

Advances in display technology are showing up in video magnifiers in the form of LCD displays from laptop computers, stand-alone flat-panel monitors, and even head-mounted displays that enable the user to view the display images by wearing special eyeglasses with built-in displays in place of lenses. Camera technology has also improved, offering the option of small, lightweight, and portable autofocus cameras that can be used for both close-up and distance viewing.

Today, it is possible to use some of the many portable video magnification systems on the market not only in the classroom, but in museums, theaters, and sports arenas. In this review, we compare two portable video magnifiers for use in museums: Betacom's VisAble VideoTelescope and Enhanced Vision System's Jordy. We also report on our experiences with a third video magnifier that was in the prototype stage when we looked at it: Clarity Solution's MobileMate. (See the sidebar at the end of the article.)

VisAble VideoTelescope

The VisAble VideoTelescope looks like a small camcorder that is held in the palm of your hand (see Figure 1). It weighs 12.5 ounces. The display is built in, which means that you look into the eyepiece to view images as you do with a camcorder. Unlike a camcorder, however, you cannot record images. The VisAble VideoTelescope can zoom up to 20X magnification for distance viewing and has a reading cap that you can put on to bring the near zoom up to 60X for close-up work. It has a horizontal field of view of 35 degrees.

Caption: Figure 1. The VisAble VideoTelescope

Distinctively shaped, raised, and colored buttons control zoom-in and out, contrast, black-and-white or color imaging, and a freeze-frame feature, referred to as image capture. These buttons are easy to find with your fingers as you hold the device to your eye. As with all telescopes, maintaining the desired image at a high magnification within the viewfinder can be a challenge. The image-capture feature is designed to make it easier to view an image once it is frozen. It can be used for reading signs or text or examining details, such as an artist's brush stroke.

Jordy

The Jordy video magnification system consists of a head-mounted display in the form of eyeglasses with displays instead of lenses and a control unit. Since the video camera is enclosed within the front section of the 8-ounce Jordy eyeglasses, the camera is pointed by head movement (See Figure 2). The Jordy head-mounted display is worn over prescription eyeglasses. A headband strap and an adjustable nosepiece allow the user to adjust the fit. Jordy offers a magnification range up to 40X with a 44-degree field of view. A lens on the front of the system can be slid over the main camera lens for reading and near viewing up to 60X.

Caption: Figure 2. The Jordy

The Jordy eyeglasses connect to an 8.5-ounce control unit the size of a pack of cigarettes. The control unit can be worn on a belt or placed in a pocket. On it are the power button, a 16-level preset magnification dial, and controls for brightness. It also has buttons for the object-locator feature, focus-lock feature, and viewing-mode selection. When viewing an object at high magnification, you use the object-locator feature to zoom the camera out and then zoom back in to the desired object. This feature gives you a way to orient the object in relation to its surroundings. The focus-lock feature is used when objects are moving in and out of the viewing field. It prevents the autofocus system from constantly changing. The viewing-mode button controls three viewing options: full color, a black-and-white high-contrast positive image, and a black-and-white high-contrast negative image.

The control unit also holds the rechargeable battery and connections for video in, video out, and an AC adapter. An optional docking stand is available with a traditional x-y table that allows the Jordy to be connected to a monitor and used like a standard desktop video magnifier.

How the Devices Performed in Museums

Six high school students and two college students, all of whom are visually impaired and use video magnifiers to do their schoolwork, tried out the VisAble VideoTelescope and the Jordy in seven museums. In the New York metropolitan area, five students went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Thomas Edison National Historic Site. In Atlanta, three students went to the Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial Center, the Jimmy Carter Presidential Center, the Fernbank Museum of Natural History, and the High Museum of Art. All eight students also visited the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh.

At the museums, the students were given a tour and viewed a variety of objects, including items in glass displays, paintings, and other objects that were not behind glass. As in most museums, patrons were restricted to a viewing distance of 10 to 15 feet for many of the items displayed. The lighting conditions varied from very dim to very bright. The students then went back on their own to view the same items they visited on the tour. In addition to zooming in on items at a distance, they also zoomed in to read posted titles and explanatory text and to attempt to make out fine details.

Some individuals with low vision prefer to use one eye (monocular vision), whereas others use both simultaneously (binocular vision). The students who were able to use binocular vision found the Jordy preferable, and those who used monocular vision preferred the VisAble VideoTelescope. The Jordy was preferred when it came to tasks that required the most magnification—especially for reading text and seeing fine details. The Jordy's wider field of view was also preferred.

Both devices did well in low light conditions, which were prevalent in the museums to help preserve their collections. The objects the students viewed were often in shadows or so poorly lit that it was impossible to distinguish details without a light-enhancing device. At the Jimmy Carter Presidential Center, the carved presidential seal on a replica of President Carter's desk was detectable with the light-amplifying features of the two devices.

Both the Jordy's object-locator feature and the VisAble VideoTelescope's image-capture feature were found to be useful. Although the Jordy is relatively simple to use, finding the controls is more difficult than on the VisAble VideoTelescope. Also, the head-mounted display was slightly uncomfortable for some of the students and messed up their hairdos.

The VisAble VideoTelescope was found to be more convenient to use because it did not require setup time. This was especially the case on the group tour, when less setup time was available. Since it is not recommended to use the Jordy while walking, some of the students placed the Jordy on their foreheads and slipped the spectacles over their eyes when needed.

The students thought that the fact that the VisAble VideoTelescope is a lightweight, one-piece unit was a distinct advantage and appreciated that it is much more inconspicuous than the Jordy. They also thought that the use of the VisAble VideoTelescope's reading cap was inconvenient. It also should be noted that museums do not allow the use of camcorders, so the VisAble VideoTelescope will attract the attention of museum security guards.

The Bottom Line

In the museums we visited, the Jordy was preferred for its higher magnification, greater field of view, and object-locator feature. The VisAble VideoTelescope was preferred for its ease of use, portability, and image-capture feature. There were problems with both in the museums, but we think they worked well enough to warrant consideration. Another question is how do they compare to the simpler, less expensive technology of an optical telescope? Although an optical telescope is small, lightweight, and inconspicuous, it is limited in dim lighting and its magnification range and has no image-enhancement capability. Thus, it would appear to be well worth the additional cost to consider a portable video magnifier, such as the Jordy or the VisAble VideoTelescope for use in museums. Furthermore, if they work in museums, they may also work in many other places, such as classrooms, theaters, and arenas.

Manufacturer's Comments

Betacom: The VisAble VideoTelescope has been significantly enhanced since this evaluation took place. In lieu of the industry standard of gray-scale adjustment, Betacom's proprietary technology enables the user to selectively manipulate either the white or black image elements, thereby providing contrast-optimization capabilities in either very low light or bright light-glare situations or when going from one to the other. This capability now offers 10 different levels versus the previous version's 4 steps. A collapsible monopod (priced from $25 to $75 at most consumer electronics stores) or other supports designed for cameras or camcorders fit on the VisAble VideoTelescope and are a common accessory for long-term viewing tasks. Typical use—turning it off and on through the day—delivers a battery life of approximately 8 hours, but even with continuous use, a battery will run 3 hours (charging time is 2.5 hours). A monitor connector cable and cable kit are now available that will enable users to interconnect the VisAble VideoTelescope with a regular TV or a computer monitor.

Product Information

VisAble VideoTelescope

Manufacturer: Betacom Corporation 450 Matheson Boulevard East, Unit 67, Mississauga, ON L4Z 1R5 Canada phone: 800-353-1107 fax: 905-353-1107 e-mail: <info@betacom.com>; web site: <www.betacom.com>. In the United States: 1000 John R Road, Suite 108, Troy, MI 48083 phone: 888-350-3155 e-mail: <infoUS@betacom.com>. Price: $1,995.

Jordy

Manufacturer: Enhanced Vision Systems 2130 Main Street, Suite 250, Huntington Beach, CA 92648 phone: 800-440-9476 or 714-374-1025, 714-374-1829 fax: 714-374-1821 e-mail: <info@enhancedvision.com>; web site: <www.enhancedvision.com>. Price: $2,795.

MobileMate

Manufacturer: Clarity Solutions, 320B Tesconi Circle, Santa Rosa, CA 95401 phone: 800-575-1456 e-mail: <clarity@clarityaf.com>; web site: <www.clarityaf.com>. Price: $3,995.

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

At a glance...

Clarity Solution's MobileMate

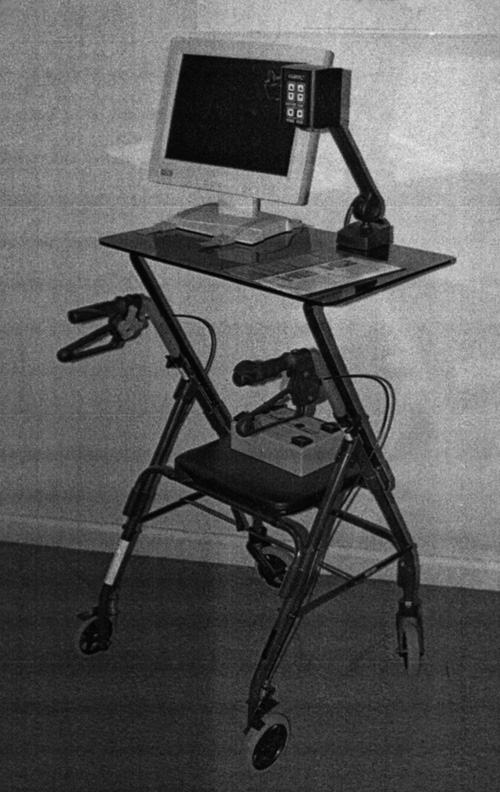

At about the time we were evaluating the VisAble Video Telescope and the Jordy, Clarity Solutions developed a prototype portable video magnification system for use in museums that takes an entirely different approach to the problem (see Figure 3). A platform is mounted on a four-wheeled walker. Attached to the platform are a 17-inch flat panel display and Clarity Solutions "flex arm" autofocus camera that can be used for near and distance viewing. A rechargeable battery is mounted on the walker, below the platform.

Caption: Figure 3. The first Mobilemate

As a prototype, the MobileMate showed promise. It provided a stable image that the students and the tour guide could all view together, a feature that appeals to museum personnel. The tour guide at the Metropolitan Museum of Art found it to be helpful in conducting the tour. She could zoom in and out herself, pointing out details, and then move on to the next art object. At the Edison National Historic Site, the device was successfully used to view a museum videotape by pointing the camera at the video monitor. Magnification was good: 30X at distance and 60X at near.

The students made suggestions, including improving the maneuverability, contrast, access to controls, and ability to raise and lower the platform easily. Clarity Solutions addressed their suggestions and redesigned the MobileMate, which was launched in October 2001 (see Figure 4).

Caption: Figure 4. The redesigned Mobilemate

The following Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation interns contributed to this article: Erika Cenec, Gary Chan, Leah Clesson, Brian Donegan, Tyler Kirk, Russell Koegler, and Galina Tulovsky.

A First Look at Windows XP

If you take even a moderate interest in the world of computer technology, you may have noticed that Microsoft has rolled out yet another new version of the Windows operating system. Windows XP is the newest operating system from Microsoft, and it has many new features. On the whole, XP is an improvement over previous versions of Windows, but it may prove difficult for users of screen magnification products, as a result of a new technology that handles the drawing of text and graphics. If you're blind or visually impaired, probably the first questions that come to mind are these: Will XP work with my screen reader, magnification software, scanner, or other adaptive technology? And what about my current applications? Will they work with XP? Will I have to upgrade my computer, and how much horsepower memory and CPU power does XP require? If you're concerned about any of these issues, then read on. This article gives you an overview of Windows XP and its compatibility with the current crop of adaptive software employed by blind computer users.

Similarities and Differences

The good news is that if you know how to run Windows 95, 98, or Millennium (ME), then you know how to run XP. XP is not just an upgrade; it is a near-total revamping of the Windows operating system. XP is generally downwardly compatible with older windows software, but Microsoft warns that there could be some incompatibility with some applications. But on the whole, you should have little trouble running your current applications on XP.

But what about adaptive technology? If you're thinking of upgrading to XP, you will probably also have to upgrade your screen reader, screen magnifier, or other adaptive software to be compatible. (See the table at the end of this article for a list of some XP compatible screen readers, magnifiers, and other products.) All the major vendors of adaptive technology are working hard to produce XP versions of their products, and most of these versions should be available by the time this article appears. XP is now a fact of life, and the vendors of adaptive technology are wasting no time getting on the bandwagon. But XP is not without problems, especially for users of large print.

The Problem with Graphics

Windows XP uses a new mechanism for drawing graphics, which may have a negative impact on users of screen readers or screen magnifiers. This new technology, known as GDI+, permits applications to draw both text and graphics to the screen. The problem is that GDI+ renders text as a bit-mapped image, which cannot be accessed by screen readers. GDI+ also confuses screen magnification software.

GDI+ is used in Windows XP Home and Professional, as well as XP Office. Currently, GDI+ looks like it's a more significant problem for screen magnifiers than it is for screen readers. According to the screen reader developers I spoke with, they are working on the problem. GDI+ could become a serious problem for visually impaired computer users, as more software developers begin to rely on it to draw screens.

For users with visual impairments, probably the biggest difference between XP and the other versions of Windows is the user interface. The new look involves the Start Menu and Task Bar. XP shows you the Start Menu in a double column, with the most recently used programs in the left column and the rest of the Start Menu in the right column. This new arrangement talks just fine and does not seem to be a problem with the screen readers I've tested.

Keyboard Shortcuts

If you're a fan of keyboard shortcuts, then fear not. Another bit of good news is that XP still supports all the keyboard shortcuts found in previous versions of Windows. Control+Escape still takes you to the Start Menu, Tab cycles through Dialog Boxes and other controls, ALT+Tab cycles you through running applications, and so on. For a complete list of keyboard shortcuts, point your browser to <www.microsoft.com/enable>.

System Requirements

One of the most important questions you may have about XP is, "Does my PC have enough power to run it?" Microsoft recommends that you run XP on a computer with a 300 megahertz processor, 128 megabytes of memory, and 1.5 gigabytes of available hard disk space. A CD-ROM or DVD drive is also required, as is an 800 × 600 super VGA video adapter and monitor.

The systems requirements do not take into consideration that users may be using adaptive equipment, which can increase the demands for memory and processor speed. Your performance will increase if you run XP on a system equipped with more memory and a faster processor than the one recommended by Microsoft.

The Two Flavors of XP

As you may have heard, Windows XP comes in two basic versions: XP Home and XP Professional. XP Home, as its name implies, is designed for household users. It is well suited for those who run a single stand-alone computer at home or a small peer-to-peer home network. On the other hand, XP Professional is intended for business applications and users with more demanding computing requirements; it allows you to log on to both peer-to-peer and client-server networks. It also has increased security and lets you encrypt your files and folders for added security. If you work from home and have to log on to a remote network, then you should go with XP Professional. Moreover, both XP Home and XP Professional will let you log on to the Internet to perform web browsing, e-mail, and other functions. But if you want to log on to a client server network remotely, XP Professional is what you need.

XP's Native Adaptive Technology

In terms of built-in adaptive technology, XP Home and XP Professional are exactly the same. Both versions include Microsoft's Narrator, Magnifier, On-Screen Keyboard, and Utility Manager. For users with disabilities, this makes the selection process a bit easier. You get the same accessibility features in both versions. Here's a basic rundown of the built-in XP adaptive technology:

- Narrator is a basic screen reader that provides speech output for blind computer users. It is not intended to replace more powerful commercially available screen readers. Rather, it is intended to help you when your normal adaptive equipment is not available.

- Magnifier is a screen-magnification program that provides up to nine times magnification for users with low vision. It also lets you adjust contrast settings and select normal or inverse video. As is the case with Narrator, Magnifier is not intended to replace more powerful software-magnification programs.

- On-Screen keyboard is an application designed for users who have difficulty typing on the physical keyboard or using the mouse. The On-Screen keyboard shows you a picture of the keyboard on the screen. This keyboard can be programmed to highlight one key at a time, letting you select the highlighted key with an external switch mechanism.

- Utility Manager lets you control all the internal accessibility applications found in the operating system and set the preferences for each utility.

Some New Features

In an article this size, it's impossible to cover all of XP's new features in detail. I will, however, try to describe several of them that may have a positive impact on users. If you use a network or the Internet, XP has a built-in network-repair feature that I'm sure will come in handy. If for any reason, you lose your connection to a local area network or to the Internet, you can click on the Repair Network icon to get back up and running. The Repair Network automatically rebuilds your connection to the Internet and reestablishes your IP address. For nontechnical users, this feature can be beneficial to say the least.

Since many users now burn their own CD-ROM disks at home, at school, or at the office, XP includes direct support for compact disk writers. You do not need to purchase third-party CD burner software, as with other versions of Windows. This is not a sophisticated program like Adaptec's Easy CD Creator, but it does let you send files to a CD writer.

XP also offers Remote Assistance, a powerful feature that allows another individual to take over control of your computer from a remote location to help you solve problems or to give you complex technical support. Remote Assistance works across a local area network or the Internet and can become active only with your permission and knowledge. You must grant permission to the remote individual before he or she can take control of your computer.

Once you grant permission, the individual can control your keyboard and mouse and can see everything displayed on your screen. According to the screen-reader developers I've talked with, the Remote Assistance and remote desktop features are unlikely to work with speech, at least for the time being. This is something that Microsoft needs to work on because it has tremendous potential benefits for users with disabilities.

Famous Last Words

It is generally believed throughout the computer industry that XP appears to be an improvement of the Windows operating system. For better or worse, XP is now a fact of life, and it's in your best interest to become familiar with it. Windows XP includes all the accessibility utilities and features found in previous versions. If you are considering upgrading and your computer is powerful enough, I recommend that you select XP Professional because it will give you greater flexibility and security than XP Home. In particular, XP Home will not let you log on to a client's server network, something that may be important to you if you work at home. Also, it does not support multiple monitors, a feature that may be attractive for users with low vision.

My biggest concern with XP is the new GDI+ technology that interferes with screen magnification software. Until Microsoft fixes this problem, XP could prove to be a significant challenge to persons with low vision.

Accessibility Features of the Sanyo 4700 Cellular Phone

Purchasing a reasonably accessible cell phone and a service plan that meets your needs can be daunting, at best, and completely overwhelming, at worst. This article reviews the access features and related issues for the Sanyo 4700 cellular phone, marketed and supported by Sprint PCS <www.sprintpcs.com>. It also provides a specific example of steps that can be taken to resolve some of the problems. My research suggests that this is the most accessible product currently supported by Sprint PCS. If readers find this format useful, I will use it to review the most accessible products supported by other major wireless providers.

Which Comes First: The Phone or the Provider?

Many people who are blind have purchased cell phones with some accessibility features only to discover that the phones are not supported by their local providers or are supported, but the providers do not have a plan that meets their needs. The Sanyo 4700, for example, is offered by Sprint PCS, which serves most major metropolitan areas but does not serve most rural regions. Therefore, it is generally best to purchase a plan and phone directly from a service provider, rather than through a third-party supplier. Keep in mind, though, that you are probably the first blind person the customer service representative has ever dealt with, and he or she probably has little or no training or information about any accessibility considerations you will need or that may be available from the provider and manufacturers.

This was definitely the case in the three major service provider stores I visited as part of this research. Despite these problems, I found the representatives to be helpful and interested. In all cases, once they understood the barriers that blind people face in setting up and using the phones, they were willing to go the second mile to ensure that my experience was as positive as possible. This is a vast improvement over just a few years ago when I was asked, "What would a blind person do with a cell phone anyway?" Having said all that, let's get on with the phone itself.

The Sanyo 4700

Adequacy of Tactile Markings

The Sanyo 4700 has an easily distinguishable number pad and function keys. The Power switch is recessed and located at the base of the unit away from the other keys. There are tactile markings surrounding the 5 key, function keys are shaped differently from number keys and are slightly recessed, and the menu key has a unique shape and texture.

Status Indicators

There are distinctive and unique tones when the phone is turned on or off. There is also a unique tone for low battery, which sounds about five minutes before the phone loses power. There is a verbal prompt when voice mail is received. If voice mail is received while the phone is turned off, the verbal prompt is spoken when the phone is turned on.

Dialing Options

As noted, the number pad is easy to identify and has unique markings near the 5 key. In addition, the phone supports voice dialing and 1-key dialing. The Phone Book and setting up these dialing features require assistance from a sighted person to program them. When using Voice Dial, the user is prompted to say the desired name. If the phone does not understand, it will verbally ask for the name to be repeated.

Caller ID

The Caller ID function is not accessible. However, there is an interesting work-around, called Voice Ringing, that I found useful. When Voice Ringing is activated, Caller ID information is associated with Voice Dial entries in the phone book. Thus, if a name and number are stored in the voice dialer, the entry will be spoken when a call is received from the associated phone number. For example, you could create a Voice Dial entry for "Jay Leventhal at AFB" and associate it with Jay's phone number. If Jay calls, your voice will announce "Jay Leventhal at AFB." However, if Jay calls from a different number that has not been stored, the phone will announce "Unknown Caller." Though not ideal, I found this limited Caller ID feature to be useful in screening calls.

Roaming Status

The phone has a Guard feature, which, when activated, requires the user to take extra steps when making or receiving a Roaming call. This feature is not accessible but can be used with practice and is useful to prevent Roaming when in a digital service area.

The Menus

Inaccessibility of on-screen menus is a significant issue with most cell phones, and the Sanyo 4700 is no exception. I asked the sales representative to set all features according to my preferences and to go over the menus with me in great detail while I took notes. This process took about an hour. It requires assistance from a sighted person to change the options, but the process is less cumbersome because of this orientation. Fortunately, options cannot be changed accidentally, since confirmation is generally required.

Documentation

Sprint PCS makes all user documentation available on its web site in pdf documents. The Sanyo 4700 User Guide could not be read using Acrobat Reader 5 with current versions of JAWS for Windows or Window-Eyes, and was read but not correctly formatted when I sent it to the conversion site at Adobe.com. I used optical character recognition (OCR) to convert the pdf to text. But the text is not useful because all the key names are graphic symbols with no text representation. A typical instruction is thus rendered: "To place a call, press to turn on the Power, dial the number, and then press to place the call." The User Guide is thorough and has been useful to me in combination with all the notes I took during my orientation.

Next Steps

The next step was a call to Sprint PCS Customer Care to confirm my findings and ask for solutions. I explained that I am blind. I then described, using specific examples, how my lack of access to the documentation and to prompts and menus displayed on the screen interferes with my ability to make and receive calls. I mentioned Section 255 of the Telecommunications Act and how I know that companies are required to make their products and services accessible to people with disabilities when doing so is readily achievable. I asked if the representative could recommend a different phone that would better meet my described needs, or if there were features on this phone that might not have been explained to me. I also asked for documentation in a format I could use. I explained that this request would not be satisfied by merely converting the pdf document to text, since it contains graphic symbols to represent the names of keys. I said that I would be willing to contact the product manufacturer directly, but no contact information was available in the documentation or on the Sprint PCS web site. As was the case in the store, the customer representative did not have information on the accessibility of services or supported products. I am waiting for her to get back to me about these issues.

Meanwhile I know that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) maintains a current list of Section 255 contacts for service providers at <www.fcc.gov/cib/dro/service_providers.html> and a list of manufacturers at <www.fcc.gov/cib/dro/section255_manu.html>. Sprint PCS has a listed contact, but Sanyo does not. In many cases, these contacts are lawyers who are responsible for defending the turf. In any event, it will probably be necessary for me to make this contact. Depending on the outcome of my efforts, it may also be appropriate for me to file a complaint with the FCC. AccessWorld will keep you posted on my progress and the outcomes.

Important Things to Remember

I write down everything as it happens. I documented my experience in the store, my process of learning how to use features of the phone, my experience in using the documentation, and my phone call to the customer service representative. I will be sending e-mail messages to the Section 255 contact and to the FCC (if necessary), and all this documentation can be used to support my case.

Is it a lot of work? Yes. Is it worth it? I'll see. We've made a lot of progress regarding access to other products—we can do it again.

No title

Mt. Everest Climber to Provide Advice on Freedom Scientific Products

Erik Weihenmayer, best known for being the first blind man to reach the summit of Mt. Everest, was appointed chair of Freedom Scientific's newly created Product Advisory Board; he will also serve as company spokesperson. As chair, Mr. Weihenmayer will meet with the board and company managers three to four times a year to provide feedback on product ideas and suggest enhancements to existing products. Mr. Weihenmayer used a Braille 'n Speak notetaker during the Mt. Everest expedition to provide web updates to those tracking his progress as he ascended the mountain. For more information, contact: Freedom Scientific; phone: 800-444-4443 or 727-803-8000; web site: www.FreedomScientific.com.

Internships for Teens Who Love Technology

The American Foundation for the Blind's (AFB) National Technology Program will begin recruiting in March 2002 for its fourth summer internship program, the 2002 Product Evaluation Laboratory Student Internship Project, which is funded by the Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation. High school students with visual impairment are invited to apply for two positions at the AFB Product Evaluation Lab in New York City, two positions at the AFB National Technology Program in Chicago, IL, and two spots at the AFB National Literacy Center, in Atlanta, GA. Applicants must be residents of the city in which the internship will take place. Applications are available. For more information, contact: Mark Uslan, AFB, 11 Penn Plaza, Suite 300, New York, NY 10001; phone: 212-502-7638; e-mail: <muslan@afb.net>; web site: <www.afb.org>.

Cassette Tutorial

The VIP's Introduction to Computers is a three-hour cassette guide designed to help blind or visually impaired people who do not own a computer decide if buying a computer is right for them. The guide costs $20. For more information, contact: John Wilson; phone: 011-44-113-257-5957; e-mail: <jwjw@onetel.net.uk>.

Updated Web Site Accessibility Analysis Tool

Bobby Worldwide, the newest version of the Center for Applied Special Technology's (CAST) web-based web site accessibility analysis tool, is available. A single user copy costs $99, a site license costs $3,000 per server, and a multiple server site license costs $2,000 per server for 10 or more servers; additional pricing options are also available. For more information, contact: CAST; phone: 978-531-8555; e-mail: <cast@cast.org>.

Tired of Folding Your Tens and Twenties?

Note Teller 2 is the newest version of Brytech's bank note reader. The handheld device is designed to speak, in English or Spanish, the denomination of new and old U.S. paper currency. The new version is designed to scan faster, use less energy, to weigh less than previous versions. The cost is $295 plus shipping. Enhanced Note Teller 2 is designed to provide tactile output through vibration of the denomination of new and old U.S. currency; speech is not included. The cost is $325 plus shipping. Owners of previous Note Teller editions may upgrade their old units to recognize the newly designed currency by shipping their old Note Tellers to Brytech for a cost of $85. For more information, contact: Brytech, 600 Peter Morand Crescent, Ottawa, Ontario, K1G 5Z3, Canada; phone: 800-263-4095; fax: 613-731-5812; web site: www.brytech.com.

Magnify This

Scan and View, a new magnifier, was released in February 2002. Scan and View works with a USB flatbed scanner to offer a fixed resolution view of printed or photographed information. Among its features are: color or black-and-white viewing, 24X magnification, image rotation, and large navigation button. The cost is $79.95. For more information, contact: Premier Programming Solutions; phone: 517-668-8188; e-mail: <info@readingandeasy.com>; web site: <www.readingandeasy.com>.

Zoom in on This

In fall 2001, Ai Squared released ZoomText version 7.1, a new version of Ai Squared's magnification and screen reading software. Version 7.1 is designed to support Windows XP, Microsoft's latest operating system, and features CompatibilityOne, support for all Windows operating systems. Level 1, which includes a magnifier, costs $395; Level 2, which includes a screen reader and magnifier, costs $595. ZoomText 8.0 is scheduled to be released in spring 2002. The newest version is designed to offer faster computer access, new magnification technology, narration of program and user activity, comprehensive reading commands, and CompatibilityOne. The pricing is the same for version 8.0. Low-cost upgrades to ZoomText 7.1 and 8.0 will be offered to all registered users; an annual ZoomText subscription plan is offered, which includes all upgrades and maintenance releases during the subscription period. For more information, contact: Ai Squared; phone: 802-362-3612; e-mail: <info@aisquared.com>; web site: <www.aisquared.com>.

Maintain Your IBM Home Page Reader

The 3.02 maintenance update is available for licensed users of IBM Home Page Reader versions 3.0 English, 2.5 English, and 2.0. Among the benefits of the 3.02 update are: expanded operating systems support for Microsoft Windows XP Professional and Consumer, 2000, Millennium, 98, and 98 Second Edition; support for Microsoft Internet Explorer Internet Browser 6.0, 5.5, and 5.0; enhanced speech performance, such as automatic reading of pure text pages, navigation of large Select Menus, and additional page navigation commands; and IBM ViaVoice TTS version 6.02 text-to-speech runtime, including support for US English, UK English, German, French, Finnish, Italian, Portugese, Brazilian, and Spanish. The upgrade is available for free download at www-3.ibm.com/able/hpr3upgrade.html. For more information, contact: IBM Accessibility Center; phone: 512-838-9735.

Keep the Customers Satisfied

Each time you've made a hotel reservation, had questions about your bank account, booked an airplane flight, or wondered why your cell phone wasn't saving voice mail messages, chances are you've had a conversation with a customer service representative. Typically, we address these kinds of concerns by dialing an 800 number and talking with someone whose computer screen holds all the information we need. More and more of these human assistants happen to be blind people using assistive technology. In the hospitality industry, utilities, wireless communications, and elsewhere, blind people can be found among the ranks of sales and support personnel.

The three chosen for this article have been on the job from fewer than two years to more than 20 and should give prospective job seekers and employers a sense of the vast possibilities.

Delta Dawn

When Dana Nichols, of Montgomery, Alabama, lost her medical insurance because of the breakup of her marriage a few years ago, embarking on a new type of employment may not have been the most apparent solution to some people. She had worked as an adjunct professor, teaching college English for many years, but the job offered no medical benefits, and she was spending $400 per month for prescription drugs. Her status as a woman, nearing 50, and blind might have been counted by some as three check marks in the liabilities column, but Nichols was undaunted.

"I just sat down and made a list of all the kinds of things I could do," Nichols says in her melodious Alabama accent. A new Delta Airlines reservation center had opened in Montgomery, and working there was among the things that sounded like fun.

A counselor from the state's vocational rehabilitation agency became involved in her pursuit. "She was wonderful," Nichols recalls. The counselor "badgered and pestered" her prospective employer relentlessly, and Delta Airlines ultimately warmed to the idea of giving a blind person a try. In August 2000, her training began with the promise that if she survived it, she would be hired.

Although Nichols's experience is not particularly representative of what many blind and visually impaired job seekers encounter, it may well serve as an example of how the vocational rehabilitation system can work. After a few months of training and supervision, Nichols was working independently and competitively as a Delta Airlines reservation sales representative. She handles calls from customers who may be anywhere in the United States. Whether they are looking for the lowest fare or trying to retrieve a pair of lost sunglasses, her job is to handle calls, satisfy customers, and sell airline tickets.

The proper selection and installation of and training in assistive technology that works for the job can make or break this kind of employment situation. Bartamaeus Group, a Virginia-based consulting firm, modified Nichols's workstation and provided necessary training. Nichols uses a combination of braille and speech to do the job.

When she first turns on her computer, there is required reading for all personnel. For speed, she usually addresses this task with the speech synthesis provided by JAWS for Windows (JFW) 3.7. The information covered may include new security measures, delays to be expected, or the weather report in Atlanta. When she is finished, she presses a key on her keyboard, and the customer calls begin.

Her dual-purpose headset carries the voice of her customer in one ear and the synthesized voice of her screen reader in the other. Her greatest tool, however, in searching for schedule and fare information, is her HandiTech, an 80-cell refreshable braille display with a built-in computer keyboard. Reading information from tables of schedules and fares in braille is much more efficient, she says, than trying to glean needed numbers by listening. Sales representatives are evaluated on the basis of calls handled and tickets sold, and to be competitive as a blind person, Nichols has needed to orchestrate her multisensory tools in just the right way. She may listen to JFW, for instance, running rapidly through a screen to find her place. Once there, she silences the voice and peruses the facts in braille.

Nearing her two-year mark on the job, she now handles 70 to 100 calls daily and says that her average call-handling time (5 minutes) is near that of her sighted coworkers. (In the beginning, her average call took 10 minutes to complete.)

While her wages aren't high (starting at about $10 per hour), her benefits are excellent. The prescriptions that previously cost $400 a month now cost only $36, and she has a 401K plan, paid vacation, otherwise excellent medical coverage and—the benefit that keeps all employees smiling—the privilege of flying anywhere, anytime, that Delta Airlines flies, for free. At least two more blind people have been hired to work as reservation sales representatives in other Delta Airlines call centers since Nichols began, which is perhaps the best indication of how well things are working out.

Take the "A" Train

Nancy Ungar, who works as a sales representative for Amtrak in the company's Riverside, California, phone center, uses similar equipment to Dana Nichols's setup, but has gone through many evolutionary stages of assistive technology along the way. When hired in April 1980, her only method of accessing Amtrak's computerized schedule and fare information was holding the CRT lens of an Optacon to the monitor. No longer manufactured, the Optacon was one of the first devices that enabled blind people to access printed information directly. The user would guide a lens over printed characters with one hand and, with the index finger of the other hand, receive a tactile representation of the image. Compared with the direct access provided by braille displays today or 400-plus words per minute babbled by speech synthesizers, this technique seems painstakingly slow. Still, it provided the access to the computer screen necessary to get the job done. Ungar recalls that sometimes her arm would get incredibly fatigued from holding the lens against the computer's screen. Yet, she continued to receive positive evaluations, to get pay raises, and to work competitively.

After 10 years on the job, Ungar was thrilled when her employer added a 40-cell Navigator to her workstation, giving her direct braille access to the information needed to assist customers. Today, she uses an 80-cell PowerBraille display. Although her system is equipped with JFW 4.0 and has speech capabilities, Ungar rarely uses speech. In addition to blindness, she has a significant hearing impairment (she wears two hearing aids and uses an amplified telephone on the job) and thus finds braille much more efficient than synthesized speech.

"My job is to sell Amtrak," she explains simply, but there are many other kinds of calls that come her way in the 80 or 90 phone conversations conducted in a typical eight-hour day. She fixes mistakes, arranges for special services, and explains fare structures. Although her system is Windows based, the software used for tracking information on fares and schedules, called Railroad, is a DOS application. Ungar uses a Braille Lite 18 and a Perkins brailler to take notes on customers' calls. "My call time is a little longer than some sighted agents," she says, "but my sales are high."

Ungar is the only blind person working in this capacity for Amtrak, but she says there are agents with other disabilities in the Riverside call center. After 21 years, she quips, at age 47, that the best part of her job is going home. In a more serious vein, she points out that she takes satisfaction in knowing she has done a procedure well, helped another person, and been productive. She earns $35,000 to $40,000 a year, has excellent medical coverage, a good retirement plan, and significant savings on train travel. "I have very good bosses," Ungar says. "They expect me to have the same statistics and attend the same trainings as everyone else."

Call on Me

Scott Hegel, age 39, is pretty sure that he's the only blind person anywhere doing his particular job. He also finds that situation ironic, since the work is so easily adapted with assistive technology. As a business application consultant for Nors tan Communications in Milwaukee, Hegel is responsible for selling and installing PBX phone systems in hospitals and businesses nationwide. Yet, he rarely leaves his desk.

With Hyperterminal and a 56K modem, he dials into computer systems running customers' 100-plus phone systems anywhere in the country. He can install, adjust, and repair the phone features of a customer's multiline telephone system. Sometimes, he trains a new system administrator on the layers of features provided in a new voice mail system. Sometimes, he helps get into a voice mail box that has been inadvertently locked. He may move, consolidate, or alter mailboxes and features—and he does all of it from his own keyboard.

Hegel uses JFW 3.7 and an 80-cell PowerBraille. His braille display shows all the functions and features of a given system easily. He says he has learned the software of hundreds of such communications products—Octel, ZMX, Audix, and many others. "I'm not a programmer per se," he says, but he has mastered the quirks and details to make software work the way a customer needs it to.

Some companies do not have a designated system administrator for their phone systems. In that case, Hegel provides the training and troubleshoots problems himself. "I may be answering a question for an employee somewhere in Texas," he says, "and they usually don't even know that I'm in Milwaukee." Although his system offers speech, he relies primarily on the braille display to do his job. For storing phone numbers and appointments, he uses the Parrot Voice Mate, a personal organizer with voice recognition.

A self-proclaimed "phone freak," Hegel loves his job and would recommend it to others. His salary is in the $40,000 to $45,000 range, his medical and vacation benefits are excellent, and he is interacting with interesting people every day.

Like Nichols and Ungar, Hegel is the only blind person in his particular place of business. Also like the others, he rarely has occasion to mention his blindness to the person he is assisting. All three depend heavily on assistive technology, particularly braille, and they all say they would recommend the job to others.