This is the second of two articles on the three leading screen magnifiers. In the July issue, we evaluated LunarPlus, version 5.1, from Dolphin Computer Access. In this article, we evaluate ZoomText, version 8.0, from Ai Squared and MAGic, version 8.02, from Freedom Scientific. Both products were evaluated using a list of the most commonly used features of and problems with integrated screen-magnification and speech programs (see the Product Features chart for a complete list). Both programs' performance for each feature in accessing Windows, Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, Internet Explorer, and Outlook Express was evaluated. Tests were conducted on a Pentium 3 850 computer with 512 MB of memory using the software synthesizer Eloquence from Eloquent Technologies in Windows 98 SE.

MAGic, Version 8.02

MAGic, version 8.02, is Freedom Scientific's most recent upgrade of its screen-magnification program with integrated speech support. MAGic Standard supports Windows XP Home, ME, 98, and 95. MAGic Professional supports Windows XP Home and Professional, NT, 2000, ME, 98, and 95. Each product is available as a stand-alone screen magnifier or an integrated screen magnifier with speech support.

Documentation and Help

MAGic comes with a large-print user's guide that is well organized and includes a quick Start Guide and pullout reference cards for ease of use. The user's guide includes information on installing, using, and troubleshooting the program. Separate large-print reference cards would be handy. Tutorials or training materials are not provided.

Online Help was easy to access through MAGic's Control Panel or the hotkey. Information is well organized and similar to the information in the user's guide. A drawback to the Online Help is that it can be accessed only if the MAGic Control Panel is the active window. A hotkey to access MAGic's Online Help from within other programs and a listing of hotkeys within the selected Help topic would be useful. We had to search through the MAGic Hotkeys topic in Online Help just to locate the hotkey for turning magnification on and off.

Both the User's Guide and Online Help provide information about using MAGic with other applications such as Microsoft Word, Internet Explorer, and JAWS for Windows, offering both general information and hotkeys for using MAGic in each program. This is a real plus.

The What's This? tool provides context-sensitive help for MAGic dialogue boxes. Descriptions for selected controls are displayed on screen. We found that MAGic provided speech support about 50% of the time for the What's This? descriptions.

Ease of Installation

MAGic's installation was easy, with all prompts in large print and with speech using Freedom Scientific's JAWS for Windows screen reader. You can choose between automatic installation, which installs MAGic using standard defaults, or a guided installation, which allows you to select languages and location. Keyboard commands for performing tasks are provided for each screen.

Once the installation was completed, we were returned to the desktop and were left wondering how to load MAGic. A prompt or announcement of the hotkey for loading MAGic would make the task of getting started a lot less stressful.

Navigating the Control Panel

MAGic's Control Panel presents the most commonly used magnification and speech tasks, organized on color-coded toolbars in its easy-to-use Quick Access window. The blue buttons on the Magnification toolbar include a button for increasing magnification and selecting the magnification view window. The orange buttons on the Speech toolbar offer quick access to speech functions, such as rate and verbosity (the amount of speech support provided). Picture icons and color coding make the toolbars easy to see. The Quick Access Window also can be accessed using the keyboard. Pulldown menus are available for most toolbar buttons and offer instant access to settings and features.

The menu bar on the Control Panel offers access to all magnification, speech, and advanced settings and is well organized. A hotkey pulls up the MAGic Control Panel from any location.

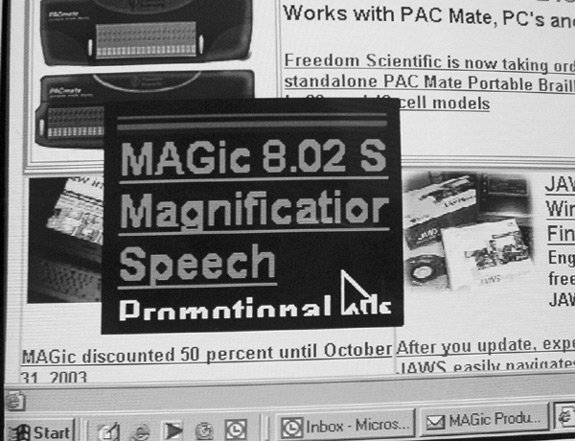

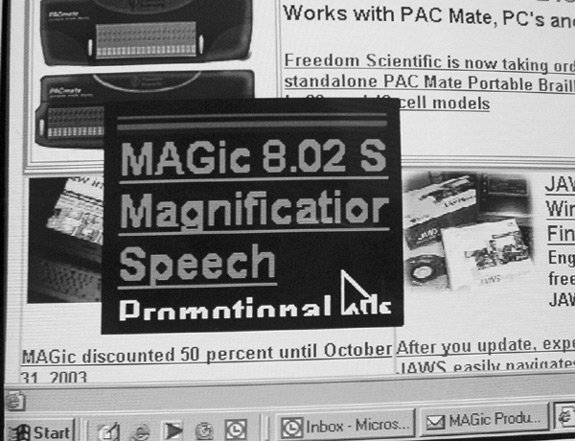

Caption: The MAGic Control Panel is color-coded for easy identification of toolbar icons and includes pull-down menus to access features quickly.

Magnification Settings

MAGic offers magnification from 2 to 16 times. Magnification can be turned on or off and increased or decreased through buttons on the User Interface toolbar or menu bar. Hotkeys can be used to adjust magnification "on the fly," and speech output of changes is announced. At a 1-times magnification, or normal view, color settings and speech are retained. When magnification is turned off, color settings are lost, but MAGic retains speech support, which is handy for the Internet. Also, when magnification is turned off, the magnification button on the Control Panel toolbar becomes animated or spins, making it easier to locate the button visually when you want to turn magnification back on.

Setting the View

MAGic offers four magnification views—full, lens, overlay, and split. In all but the full view, view windows can be resized, and the thickness and color of the window border can be adjusted. The overlay view magnifies a static window in the lower right corner of the screen. The lens view magnifies a small window that moves with the mouse pointer. Split view magnifies the top, bottom, right, or left section of the screen, leaving the other sections unmagnified. Views can be selected from the Control Panel through buttons on the Quick Access window, the Magnifier menu on the menu bar, or toggled using a hotkey.

The ability to customize the size of the view window and the thickness and color of the window border are useful features. We had difficulty locating and switching between the split-view modes. Adding the different split-view options to the main list of choices would make this task easier.

Color/Contrast Settings

Color and contrast settings are limited in MAGic to toggling inverted colors on and off. This feature inverts all colors of the currently selected color scheme. Inverted colors can be selected for the Magnification window only, for the unmagnified window only, or for both windows. Custom or preset color schemes need to be selected from the Display option under Control Panel in the Windows Start menu.

MAGic's automatic text smoothing is set always to be on. To turn smoothing off, select the Display option from the Magnification menu on the Control Panel menu bar. When automatic smoothing was enabled, the text and graphics were clear and easy to read up to 12-times magnification, after which the images became increasingly pixilated. With automatic smoothing turned off, the text and graphics began pixilating at 3-times magnification. It was surprising that automatic smoothing worked better on the Internet. When we viewed the Eddie Bauer web site, <www.eddiebauer.com>, and Amazon's web site, <www.amazon.com>, automatic smoothing worked well on the text and graphics up to 16-times magnification. With this feature turned off, images pixilated at 3-times magnification.

Tracking

MAGic tracks by mouse pointer, cursor, menu, control, tool tip, and window. Tracking also can be defined by area and alignment.

In both Word and Excel, the cursor tracked easily by word and line or cell by cell, always keeping the focus in the center of the screen, which made it easy to locate the cursor. In Internet Explorer, tracking followed the cursor as we moved through a web site by line or link, again always placing the focus in the center of the screen. In Outlook Express, tracking through messages in the In Box and between the folder tree view and list box was smooth. For both reading e-mail messages and creating new messages, the cursor tracked between fields, keeping the field name in view in the center of the screen. We had similar success tracking dialogue boxes and menus. In all programs, when the focus was moved to the menu bar and returned to the window using keyboard commands, we were never returned to the same place and had to search for the cursor.

When we used the mouse to navigate and select items, tracking was jumpy and inconsistent. Tethering the mouse pointer to the active cursor would improve tracking, especially in dialogue boxes and Help windows.

Caption: In MAGic's Lens View mode, the size and border of the magnified area can be customized.

Speech Output

MAGic is available with integrated speech support or can be teamed with Freedom Scientific's JAWS for Windows screen reader. If JAWS is used for speech support, MAGic automatically turns off all speech functions. The ability to pair the JAWS screen reader with MAGic, as needed, was a real plus.

MAGic's screen magnifier with speech support provides speech output for most functions accessed by the mouse or keyboard, including reading documents and web pages, labeled graphics, window titles, menu bars, and menu list items. A variety of languages is supported, and verbosity settings allow you to customize the speech rate, voice, and other functions.

In Word, speech support is provided as you type by character, word, or both, and documents can be read from start to finish with a hotkey. We found speech support for typing and reviewing documents to be marginal. Speech is delayed when you use navigation keys to read words or lines, and we frequently encountered instances in which speech would not read at all. Speech support for Excel is limited to speaking menus and dialogue boxes. The contents and location of cells are not spoken. In Internet Explorer, web sites can be read to the end using the MAGic hotkey or Read Word, Line, or Link using navigation commands or through the mouse. In Outlook Express, received e-mails can be read using the read-to-end hotkey, and new messages are spoken as you type. In the In Box and other folder list views, MAGic speaks the details of the message.

MAGic's application-specific commands enhance the speech support for Word, Excel, and Internet Explorer. In Internet Explorer, a hotkey reorganizes the web page in a single-column format, and links can be easily accessed through the List Links dialogue box.

Extra! Extra!

A new feature of MAGic 8.02 is the bilingual user interface that allows MAGic menus, help information, and dialogue boxes to be spoken in either English or Spanish. MAGic also offers mouse enhancements that allow you to customize the size, shape, and color of the mouse pointer.

ZoomText, version 8.0

Ai Squared offers ZoomText 8.0 in two product versions—Magnifier, a stand-alone screen magnifier, and Magnifier/Screen Reader, an integrated screen magnifier and screen reader. Both versions support Windows XP, 2000, ME, and 98, but no longer support Windows 95.

Documentation and Help

ZoomText comes with a user's manual and Quick Reference Guide in large print. Both are well organized and provide useful information on installing, using, and troubleshooting ZoomText. It would be helpful to have some of the key features and hotkeys listed on one or two cards for ease of use. Although no training materials or tutorials are provided, Ai Squared says that an integrated CD-ROM tutorial is in the works.

Online Help was easy to access from the main Control Panel and contains the same information as the user's guide. Text descriptions for each Online Help category are provided with graphics for visual recognition. Context-sensitive help is available through a Help button for every ZoomText dialogue box. The main drawback we found is that Online Help is accessible only when ZoomText has focus. A hotkey to access Online Help from within other programs would be a helpful extra.

New to ZoomText 8.0 is the Help tool. We found this tool to provide reliable, on-demand help for ZoomText. The Help tool is accessed through the Help menu in the Control Panel or with a hotkey and provides descriptions of any toolbar button and its associated hotkey on screen and with speech.

Ease of Installation

Installation prompts for ZoomText are provided in high-contrast large print and with speech. ZoomText now offers the option to install it automatically using preset options or to install it using custom options for selecting the location and synthesizer. In either installation mode, instructions were easy to follow on the screen or with speech support. Keyboard commands for selecting options and buttons are spoken, and the mouse pointer is automatically placed at the default button for each screen.

Conflicts in daisy chaining (the way that screen reader and magnifier software obtain full information about what is drawn on the screen) may occur when you install current versions of more than one screen reader or magnifier on a computer running a Windows XP home or Professional, NT, or 2000 operating system.

Navigating the Control Panel

ZoomText's main Control Panel has a new look. The toolbars are streamlined to one row, and only the most commonly used features are represented. Each toolbar button includes a picture icon and a large-print text label for easy identification. The Control Panel for the magnifier-only version offers one toolbar that presents commonly used tasks for magnification and display. The Magnifier/Screen Reader Control Panel offers the option to switch between the Magnifier and Screen Reader toolbars. The Screen Reader toolbar offers quick access to commonly used functions related to speech, such as the speech-rate and verbosity settings. Most toolbar buttons have an associated pulldown menu that offers quick access to frequently used settings. Clicking on the toolbar button activates the pulldown menus.

The new Control Panel also has a completely new menu bar. As longtime users of ZoomText, we found this new menu bar confusing at first. When we tried to select the type of view, it took us a while to locate choices under the Magnifier menu, Zoom Window option. Once we got into the different menus, we found that they were well organized and easy to understand. All functions that are available on the toolbars and some advanced features can be accessed through the menu bar, by mouse, or by using keyboard commands.

Caption: ZoomText's new Control Panel is streamlined and offers easy access to commonly used features.

Magnification Settings

ZoomText offers magnification up to 16 times. Magnification can be turned on or off and increased or decreased through the Magnification toolbar or Magnification menu in the Control Panel or hotkeys. The hotkey option allows you to change magnification "on the fly" with speech announcing the change, a handy feature offered by most screen magnifiers. At 1-times magnification, or normal view, color settings and speech support are retained. The most notable improvement in ZoomText's magnification is the clarity of the magnified area. We noticed a dramatic improvement in the sharpness of the images or text in a variety of color schemes and magnification levels.

Setting the View

ZoomText has reorganized its screen-view settings. Now referred to as Zoom Windows, you can select full view, overlay, lens, or four docked views (top, bottom, left, and right). In Overlay view, the lower-right quarter of the screen is magnified. In Lens view, a small one-eighth area of the screen is magnified as the mouse is moved around. In all but the Full view mode, the Zoom Window can be resized both vertically and horizontally. The docked view choices are an improvement over the previous horizontal and vertical split screens. The new organization of the screen-view options was confusing at first until we realized what it represented.

Zoom Windows can be selected from the Magnifier toolbar or Magnification Menu in the Control Panel or by toggling through the selections using the hotkey. We found the ability to switch Zoom Windows with a hotkey useful.

New To ZoomText is the Freeze Window, which allows for a particular area on the screen always to appear in the magnified window. The size and magnification level of the Freeze Window can be adjusted. We set a Freeze Window for the clock at a magnification level 1 times greater than the current magnified window and found this a useful tool.

Color/Contrast Settings

Major improvements have been made in ZoomText in this area. Selecting the Color Enhancements button on the Magnifier toolbar or through the Magnifier menu opens a dialogue box that presents a variety of options for setting colors. The Normal setting uses no color enhancements. The Schemes setting allows you to select from a list of seven preset schemes, such as black on white and invert brightness. The Custom setting allows for complete customization of the color settings, including the foreground and background colors, brightness, and contrast levels, and for defining the area to apply the new settings. Using the Custom Colors feature, we were able to control all aspects of the way the screen looked, from the color of the text to the background color, in unmagnified viewing areas. A hotkey turns Color Enhancements on and off—a useful feature when you are on the Internet.

The automatic text-smoothing feature can be set for all colors or black and white only. When we turned on automatic text smoothing for all colors, the edges of the text at magnification levels up to 16 times were sharp and easy to distinguish. With automatic text smoothing disabled, the text became pixilated at 3-times magnification.

Tracking

ZoomText offers tracking by mouse pointer, text cursor, menu, control, tool tip, and window. Tracking also can be defined by area and alignment.

In Word, ZoomText's tracking feature was seamless when we typed in a document. The cursor moved with minimal jumping from one line of text to the next. In Excel, the cursor tracked smoothly as we moved among cells, columns, and rows. In Internet Explorer, tracking was equally smooth when we used keyboard commands to move through a web page by link or line. In Outlook Express, ZoomText tracked well when we moved between messages in the In Box and when we read or wrote an e-mail message. Tracking became a problem when we created a new e-mail message because we were unable to view the Send To and Subject field names without moving the focus manually.

When we used the mouse for navigation, we found tracking to be inconsistent. Often, the mouse would get "hung up," and the screen would then jump to catch up with the mouse.

Speech Output

Only the ZoomText Magnifier/ Screen Reader version provides speech support. ZoomText provides speech output for most functions that are accessed by the mouse or keyboard, including reading documents and web pages, labeled graphics, window titles, menu bars, and menu-list items. Speech is supported by several synthesizers and is available in a number of languages. Verbosity can be set to different levels and can be customized by task or function.

Caption: Cursors and pointers can be enhanced and customized by type, size and color in ZoomText.

For reading an entire document, web page, or e-mail, ZoomText now offers two options—the AppReader and the DocReader. The AppReader allows for controlled or continuous reading within the program. The DocReader opens a separate window and displays the material to be read in a magnified format. With either reading tool, documents can be read by character, word, or paragraph or from start to finish. Both reading tools perform similar functions. We used the AppReader more frequently than the DocReader for its ease of use.

ZoomText also offers the Speak It tool. Words or links are spoken by simply clicking on them with this tool. For larger blocks of text, the mouse pointer can draw a box around the desired text, and the contents of the selected area are spoken. This tool was helpful in navigating web pages and reading links.

In Word and Excel, ZoomText provides speech output as you type by character, word or both. When we reviewed documents using keyboard commands, it occasionally misread words or lines. In Excel, speech support in reading the contents and location of cells is provided. In both Word and Excel Spell Checker, the misspelled word is not read, but suggestions and action buttons are read.

In Internet Explorer and Outlook Express, ZoomText's speech is notably better. Web pages or e-mail messages can be easily read using either the AppReader or DocReader tools, and the Speak It tool is handy for spot reading text or links. On web pages, labeled links and graphics are spoken when the mouse pointer is moved over them or when standard navigational commands are used.

Extra! Extra!

ZoomText offers mouse pointer, cursor, and text-enhancement features. All these features can be accessed through the Magnifier toolbar or menu bar in the Control Panel. Each feature can be customized by type, color, size, and transparency. These are all nice additions to ZoomText and make the task of locating the mouse and cursor and tracking text a lot easier and less stressful on the eyes.

The Bottom Line

Both ZoomText 8.0 and MAGic 8.02 are powerful screen magnifiers with integrated speech support. In over 20 hours of testing in Office 2000 and Internet Explorer, we experienced no instances of crashing. ZoomText has a lot of new features and has some real strengths in magnification and view settings, color and contrast options, mouse and cursor enhancements and tracking, automatic smoothing, and speech support. MAGic shows its strengths in magnification settings, automatic smoothing that is always on, tracking, speech-support options, the ability to team MAGic magnification with the JAWS screen reader, and support of popular applications.

The weaknesses of ZoomText include inconsistency in speech support and the confusing number of choices to perform similar tasks, such as the AppReader and DocReader. MAGic's weaknesses include its split view settings, limited color and contrast options, tracking from menus to windows, and erratic speech support. Both ZoomText and MAGic need to address documentation and installation issues, as well as to develop training materials.

Today, users have a choice in robust screen magnifiers with integrated speech support. Whether you choose LunarPlus, ZoomText, or MAGic, check them all out first to determine which best meets your needs. Remember, smart shoppers are those who do their homework.

Manufacturers' Comments

Ai Squared

"Ai Squared would like to thank AFB for performing reviews of AT products. These periodic reviews keep end users informed and manufacturers competitive with each other. There are a couple of items in the review we'd like to provide more information on.

"There are significant differences between AppReader and DocReader, which is why both features exist in the product. AppReader maintains the look (layout, colors, fonts) of documents and web pages while reading. In DocReader, you can select foreground/background colors and fonts, remove graphics, and reflow the material to fit the width of the screen."

****

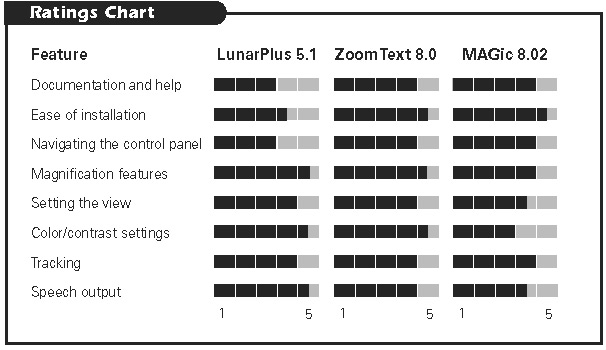

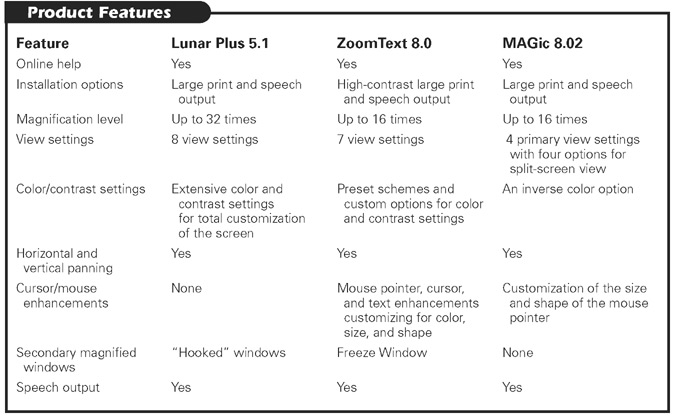

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

****

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Product Information

Product: MAGic 8.02

Manufacturer: Freedom Scientific, 11800 31st Court North, St. Petersburg, FL 33716-1805; phone: 800-444-4443; web site: <www.freedomscientific.com>. Price: MAGic Professional (with speech), $595; MAGic Professional (magnifier only), $395; MAGic Standard (with speech), $545; MAGic Standard (magnifier only), $295.

Product: ZoomText 8.0

Manufacturer: Ai Squared, P.O. Box 669, Manchester Center, VT 05255; phone: 802-362-3612; web site: <www.aisquared.com>. Price: ZoomText 8.0 Magnifier, $395; ZoomText 8.0 Magnifier/ Screen Reader, $595.