Full Issue: AccessWorld November 2006

Product Ratings

Product Ratings

Product Features

Product Features

Feature

BrailleNote GPS Version 3.5

Speech output

Yes

Braille output

Yes

Keyboard

Both QWERTY and Perkins-style braille keyboards available

GPS receiver

Holux GPSlim236 Bluetooth

Automatic route calculation

Yes, both pedestrian and vehicular

User-defined routes

Yes

User-defined POIs and waypoints

Yes

De Witt and Associates Tutorial

Braille

Yes

Yes

CD text

Yes

CD DAISY

Yes

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Features

Product Features

Feature

Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader

Size

6 inches long by 3 inches wide by 2.5 inches deep

Weight

15 ounces

Memory

64 Mb onboard plus a removable SD card for extra memory

Transfers files to a PC or PDA

Yes

Reads files from a PC or PDA

Yes

Speech synthesizer

Eloquence and RealSpeak

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Features

Product Features

Feature: BrailleNote GPS Version 3.5

Speech output: Yes.

Braille output: Yes.

Keyboard: Both QWERTY and Perkins-style braille keyboards available.

GPS receiver: Holux GPSlim236 Bluetooth.

Automatic route calculation: Yes, both pedestrian and vehicular.

User-defined routes: Yes.

User-defined POIs and waypoints: Yes.

De Witt and Associates Tutorial.

Braille: Yes.

Print: Yes.

CD text: Yes.

CD DAISY: Yes.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Features

Product Features

Feature: Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader

Size: 6 inches long by 3 inches wide by 2.5 inches deep.

Weight: 15 ounces.

Memory: 64 Mb onboard plus a removable SD card for extra memory.

Transfers files to a PC or PDA: Yes.

Reads files from a PC or PDA: Yes.

Speech synthesizer: Eloquence and RealSpeak.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Ratings

Ratings Chart

Feature: PVO; SenseView

Portability; PVO: 4.5; SenseView: 5.0.

Quality of the screen display; PVO: 3.5; SenseView: 4.5.

Usefulness for handwriting; PVO: 4.5; SenseView: 2.5.

Ability to read various text samples; PVO: 4.0; SenseView: 4.5.

Overall ease of use; PVO: 4.0; SenseView: 5.0.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Ratings

Letters to the Editor

Thanks for the Histories

I read with great interest the first two installments of "Legends and Pioneers of Blindness Assistive Technology." Anthony Candela has put together a very well-rounded account of his interviews thus far with these legends and pioneers. I am not quite old enough to remember most of them; in fact, I never met any of them. But I have been fortunate enough to use some of their products at one time or another throughout my years as a user of assistive technology. I was always very satisfied with these products, and the ongoing revolution of assistive technology is something I find truly amazing. I am now using JAWS with the Eloquence software synthesizer. Eloquence is probably the best speech I've ever heard, and I know others who may have varying opinions on that. It would be neat if Mr. Candela and/or someone else could put together a review of the various speech synthesizers and how they were created, both the software and hardware ones.

Thanks again for this wonderful series.

Jacob Joehl

Illinois

What's in a Name?

At least once a month I receive an e-mail or phone call from a vendor who wants to sell me the latest in security systems using CCTVs. Closed-circuit TVs are useful components of a good security system. The CCTVs that I'm most familiar with are devices that use a camera to enlarge text and images that are then displayed on a video monitor. I'm assuming that they found my name through a Google search because I've done some writing about CCTVs. Usually I just delete the e-mail or explain to the caller that we are talking about a piece of assistive technology for people with low vision.

What's in a name? Well, it seems to me that a name should clearly describe something without being overly complicated. CCTV is a name that seems simple enough, but it would seem that it can identify two very different things. Consequently, this has lead to the e-mails, phone calls, and confusion about the device. In an effort to clarify the situation I would like to propose that we in the field make a concentrated effort to use a more descriptive term or name to identify the devices that provide an enlarged display of printed information for people with low vision. As the technology has changed and improved over the years I would suggest that CCTV no longer adequately describes the wide variety of devices in this category.

The traditional desktop CCTV consists of a camera mounted over a moveable platform (X-Y table). This camera is cabled to a television or some type of video monitor. While this type of device is still widely used, there are numerous other options available. Models are now available that offer a variety of display and camera options. Some models use laptop computers for their display. Others connect to head-mounted displays, while some models have built-in displays. Cameras may be mounted on a flexible arm, connected to the unit via a cable like a computer mouse, mounted into a head-borne display, or integrated into a one-piece, battery-powered portable unit. CCTV just doesn't seem to describe these devices adequately.

For the past few years, I have been referring to these devices as video magnifiers. Video magnifier is probably not a perfect name for such a device, but it's a bit more descriptive than CCTV and doesn't cause confusion with security systems. Electronic magnifier might be an even better term. I'm certainly open to suggestions for a better name. My objective is to get the conversation started, and I hope that as a field we can decide on terminology that will be more useful for us and for the general population as well.

I know that the readers of AccessWorld are knowledgeable about this type of technology, and like me, will most likely have an opinion on the subject. Please submit any comments or suggestions you might have to AccessWorld, or if you prefer you can contact me directly at presley@afb.net.

Ike Presley

AFB Literacy Center

Atlanta, Georgia

The Editor responds

AccessWorld uses the term "CCTV" for consistency and because it is the term that most consumers, manufacturers, and professionals in the blindness field use. We are certainly open to change, though. For example, we use "PDA" (personal digital assistant), rather than "notetaker," to describe devices such as the BrailleNote and the PAC Mate. Notetaker seems very inadequate for a device with so many features and functions. We'd like to hear what readers think about such terminology issues.

Please let us know if you believe that video magnifier is a more appropriate term than CCTV.

Calendar

November 16, 2006

Assistive Technology: Improving Lives Daily

Warwick, RI

Contact: TechACCESS of RI, 110 Jefferson Blvd, Suite I, Warwick, RI, 02888; phone: 401-463-0202; e-mail: <techaccess@techaccess-ri.org>; web site: <www.techaccess-ri.org>.

November 17-19, 2006

World Congress and Exposition on Disabilities

Philadelphia, PA

Contact: H. A. Bruno, 210 Route 4 East, Suite 304, Paramus, NJ 07652; phone: 201-226-1446; e-mail: <wcdinfo@wcdexpo.com>; web site: <www.wcdexpo.com>.

November 30-December 1, 2006

16th Annual Assistive Technology Expo of North Carolina

Raleigh, NC

Contact: North Carolina Assistive Technology Program, 1110 Navaho Drive, Suite 101, Raleigh, NC 27609; phone: 919-850-2787; web site: <www.pat.org>.

January 24-27, 2007

Assistive Technology Industry Association (ATIA) 2007 Conference

Orlando, FL

Contact: ATIA, 401 North Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60611; phone: 877-687-2842 or 321-673-6659; e-mail: <info@atia.org>; web site: <www.atia.org>.

March 19-24, 2007

California State University at Northridge (CSUN) Center on Disabilities' 22nd Annual International Conference: Technology and Persons with Disabilities Conference

Los Angeles, CA

Contact: Center on Disabilities, CSUN, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Building 11, Suite 103, Northridge, CA 91330; phone: 818-677-2578; e-mail: <conference@csun.edu>; web site: <www.csun.edu/cod/conf/index.htm>.

March 22-23, 2007

Assistive Technology Across the Lifespan Conference

Stevens Point, WI

Contact: Wisconsin Assistive Technology Initiative, 800 Algoma Boulevard, Oshkosh, WI 54901; phone: 800-991-5576 or 920-424-2247; e-mail: <info@wati.org>; web site: <www.wati.org>.

March 26-30, 2007

18th International Conference of the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education

San Antonio, TX

Contact: Conference Services, Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education, P.O. Box 3728, Norfolk, VA 23514; phone: 757-623-7588; e-mail: <conf@aace.org>; web site: <http://site.aace.org/conf>.

April 19-20, 2007

Participation: Where It's AT (Assistive Technology for Children and Youth Conference)

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Contact: Events of Distinction, #104 - 2002 Quebec Avenue, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada S7K 1W4; phone: 306-651-3118; e-mail: <eofd@sasktel.net>.

May 2-4, 2007

Solutions for Assistive Technology Conference

Baton Rouge, LA

Contact: Adaptive Solutions, 2127 Court Street, Port Allen, LA 70767; phone: 225-387-0428; e-mail: <sherry@adaptive-sol.com>; web site: <www.adaptive-sol.com>.

June 21-23, 2007

Collaborative Assistive Technology Conference of the Rockies

Denver, CO

Contact: Assistive Technology Partners, Statewide Augmentative/Alternative Communication Program, University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, 601 East 18th Avenue, Suite 130, Denver, CO 80203; phone: 303-315-1280; web site: <www.assistivetechnologypartners.org>.

Product Features

Product Features

Feature

PVO

SenseView

Magnification range

2x to 12x

4x to 28x

Natural and inverse viewing modes

Yes

Yes

Artificial color viewing modes

No

Yes

Adjustable brightness/contrast

Three levels

Four levels

External video input

Yes

Yes

External video output

Yes

No

Power Saving Mode

No

Yes

Battery-level indicator

No

Yes

Camera focus type

Manual

Fixed

Dimensions

6.5 by 3.5 by 1.8 inches

5.7 by 3.07 by 0.88 inches

Weight

0.8 pounds

0.49 pounds

Battery life

About one hour

About five hours

Battery recharge time

Eight hours

Three hours

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Editor's Page

I was thrilled to learn in September that Jim Fruchterman has been awarded a 2006 MacArthur Fellowship from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Fruchterman is the CEO of the Benetech initiative, which includes Bookshare.org. As many AccessWorld readers know, Benetech is an online library of scanned books available for download to qualified people who are blind or visually impaired in the U.S. In February 1989, Fruchterman founded Arkenstone, Inc., to create affordable reading machines for people who are blind.

Each of this year's 25 MacArthur Fellows will receive $500,000 in no-strings-attached funding over the next five years. According to Fruchterman, his MacArthur award will allow him to further his work in technology applications and fulfill his dream of writing a book.

It's wonderful news that someone in the assistive technology field has received such a high honor. No one in our field is more innovative or charismatic. I hope this award makes more people aware of assistive technology and how it can improve the lives of people who are blind or visually impaired.

Darren Burton is now one of AccessWorld's contributing editors. Darren joined AFB TECH in 2002 and contributed his first article to AccessWorld in September of that year. He has written articles evaluating accessible voting machines, products used by diabetics with visual impairments, and a new interface for elevators. But, of course, you know him best for his groundbreaking coverage of cell phone access. When we first started publishing cell phone articles, there were no accessible products. Now there are a variety of options. Our cell phone articles are always the most popular among those we publish. Darren will keep you up to date as new products come on the market. And, as you will read next, we let him cover products other than cell phones from time to time.

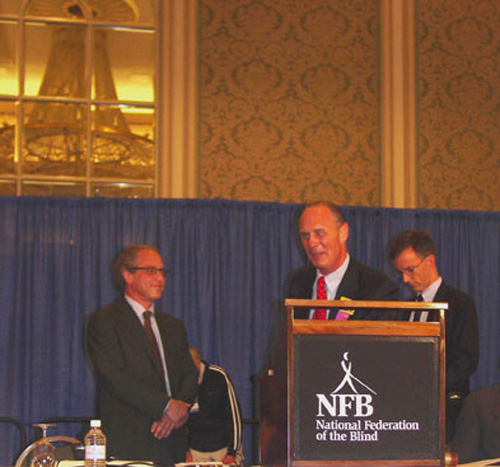

In this issue, Darren Burton evaluates the Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader. This innovative new product combines a digital camera and a personal digital assistant (PDA) to capture the image of printed text and translate it into synthetic speech. The Reader has received a lot of attention in the general media. Read about how this first-of-a-kind device performs.

Deborah Kendrick tells the story of the development and testing of the Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader. The Reader began as a prediction by Ray Kurzweil and, with the collaboration of the National Federation of the Blind and its members, was brought to market through the work of engineers and hundreds of testers from across the country. Learn the details of this product's development.

Lee Huffman of AFB TECH evaluates the PVO from Low Vision International and the SenseView from GW Micro, two small, portable CCTVs. Both products have an approximately four-inch TFT-LCD (thin film transistor) screen, various high-contrast color modes and brightness levels, adjustable magnification levels, rechargeable batteries, and weigh less than one pound. Get the big picture on these small products.

Deborah Kendrick evaluates the BrailleNote GPS 3.5 from Sendero Group. This product provides tools for enhancing your traveling experience. You can plot and follow routes, explore an upcoming trip offline from the comfort of your home or office, and hear announcements of intersections and nearby points of interest such as restaurants, banks, and tourist attractions, as well as places you add to the supplied commercial database. Find out what the latest version of this product has to offer.

Janet Ingber, author and music therapist, provides an overview of accessible standardized testing. The article defines standardized tests, describes past accessibility efforts, and explores possible future adaptations.

Anthony Candela, Deputy Director, Specialized Services Division of the California Department of Rehabilitation, presents the third in a series of articles chronicling the history of assistive technology. He interviewed more than 20 major players—inventors, company executives, and trainers—spending hours with each one. This article highlights the development of assistive technologies including electronic braille, synthetic speech, CCTVs, and OCR systems.

Jay Leventhal

Editor in Chief

Product Features

Product Features

Feature: PVO; SenseView

Magnification range: PVO: 2x to 12x; SenseView: 4x to 28x.

Natural and inverse viewing modes: PVO: Yes; SenseView: Yes.

Artificial color viewing modes: PVO: No; SenseView: Yes.

Adjustable brightness/contrast: PVO: Three levels; SenseView: Four levels.

External video input: PVO: Yes; SenseView: Yes.

External video output: PVO: Yes; SenseView: No.

Power Saving Mode: PVO: No; SenseView: Yes.

Battery-level indicator: PVO: No; SenseView: Yes.

Camera focus type: PVO: Manual; SenseView: Fixed.

Dimensions: PVO: 6.5 by 3.5 by 1.8 inches; SenseView: 5.7 by 3.07 by 0.88 inches.

Weight: PVO: 0.8 pounds; SenseView: 0.49 pounds.

Battery life: PVO: About one hour; SenseView: About five hours.

Battery recharge time: PVO: Eight hours; SenseView: Three hours.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Ratings

Ratings Chart

Feature: BrailleNote GPS Version 3.5

Ease of installation: 4.0.

Connectivity: 4.5.

Portability: 4.0 with a BrailleNote Classic or an mPower; 5.0 with a BrailleNote PK.

Online help: 3.5.

GPS accuracy: 4.5.

Documentation: 3.0.

Reliability of maps: 4.0.

Flexibility of user settings and options: 4.5.

Auditory feedback (other than synthesized speech): 3.5.

Overall rating: 4.5.

De Witt and Associates Tutorial.

Ease of use: 4.5.

Production quality: 4.0.

Clarity of instruction: 4.5.

Overall rating: 4.5.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Ratings

Ratings Chart

Feature: Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader

Documentation: 5.0.

Portability: 4.0.

Voice quality: 4.5.

Accuracy.

Simple black-on-white documents: 5.0.

Text in columns: 4.0.

Bold text: 5.0.

Italic text: 4.0.

Light text on colored backgrounds: 2.0.

Colored text: 3.0.

Product packages: 3.5.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Finding Your Way: A Review of Sendero GPS 3.5 for BrailleNote with a New Training Guide from De Witt and Associates

When the notion of using the Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) system as a navigational tool for people who are blind first garnered public attention, it sounded to many like science fiction. At best, some speculated at the time, it might be a tool that could be used by Michael May (then vice-president of Arkenstone and the leading proponent of the GPS as a wayfinding device), but not by anyone else. That was only about a dozen years ago. Today, there are three competing GPS products on the assistive technology market and murmurs of more to come. This article is a twofold evaluation; it reviews the Sendero GPS 3.5 that is used on HumanWare's BrailleNote products and a new tutorial from De Witt and Associates that is designed to assist trainers or individuals who are learning to use the product.

Identifying the Players

Michael May, president and CEO of the Sendero Group, drew considerable media attention in the early 1990s with the GPS software that he was able, as a blind person, to run and access on a laptop. The prototype was tweaked for years, and in 2000, it was made available for purchase from the Sendero Group as GPS-Talk. But only in 2001, when the Sendero Group and HumanWare (then Pulse Data International) collaborated to run the Sendero GPS on the BrailleNote family of products was the GPS actively marketed and widely available to consumers who are blind. The Sendero Group is one company, and HumanWare is another. The product is referred to by either name—Sendero GPS or BrailleNote GPS—in this article and elsewhere.

What Is GPS?

Initially intended for military purposes, the 24 satellites that circle the Earth send information on latitude, longitude, and altitude to receivers to pinpoint an individual location. When this technology was released for commercial purposes in 2000, companies developed maps and databases that identified streets, businesses, and other points of interest corresponding to these positions. A person who is blind who uses the Sendero GPS software on a BrailleNote or VoiceNote can hear all the information that these maps deliver spoken or read on the braille display.

With the Sendero GPS and other such software, the person who is blind who is walking in a familiar or unfamiliar location can identify streets; intersections; and 50 categories of businesses and landmarks, including restaurants, shops, banks, ATM machines, parks, zoos, and schools. The landmarks are referred to as POIs (points of interest). The software can tell you the direction in which you are heading; the nearest address, intersection, or point of interest; or what city you are in. In a vehicle, the software can tell you all the same things, as well as the speed at which the vehicle is traveling. In either mode, it can tell you how far—in feet or in miles—you have traveled or, on a predetermined route, how far you have yet to go.

What is perhaps most amazing to a person who is blind is the liberating ability to "look around," whether he or she is actually navigating or sitting still, to see all the streets and POIs within a designated range. For example, sitting in my kitchen, I learned from a few keystrokes that there were 863 POIs within one mile of my home—59 of them restaurants and 173 of them shops. As many other users who are blind have commented, it was astonishing to learn how many streets and businesses were in my own neighborhood that I had never known were there. With another keystroke, I could discover the address and phone number of any of these businesses. In other words, the software allows the BrailleNote user to gather the information on surrounding environments that sighted people take for granted and, as a bonus, serves as a virtual on-tap yellow pages, too.

For this evaluation, a BrailleNote mPower running KeySoft 7 was loaded with the Sendero GPS 3.5 with the Holux Bluetooth receiver. The software can, however, run on any of the BrailleNote, VoiceNote, or BrailleNote PK models. Running it on the BrailleNote PK is perhaps the most appealing, since this option gives you a personal digital assistant and a GPS system all in one unit weighing less than a pound. The software and documentation are contained on a 1GB compact flash card. If the BrailleNote and GPS are purchased together, the card will be in the slot with the software, and maps for the customer's location will already be loaded. If the two are purchased separately, installation is simple and straightforward. The compact flash card contains the user manual, command list, and online Help. A braille command summary is also included. The commercial maps and POI databases for the United States are included on CDs, packaged in a small CD album, and are labeled in both print and braille. To load any of these files into the BrailleNote, it is necessary first to transfer them, using a computer, from the CD to the compact flash card. Then, once the desired maps are on the card and the card is in the BrailleNote, maps can be accessed at any time.

Caption: Running the Sendero GPS 3.5 on the BrailleNote PK gives you a personal digital assistant and a GPS system all in one unit weighing less than a pound.

It should be noted that using the Bluetooth receiver was particularly welcome, since there were no wires from the receiver to get in the way while I was walking or traveling in a car or bus. Although I used a traditional headset or earbuds for listening to the speech output, a Bluetooth headset could also be used, thus eliminating the inconvenience of wires altogether.

Learning to Use It

De Witt and Associates is a New Jersey-based company that provides assistive technology training and publishes training materials. Its newest courseware title was Teaching and Learning the BrailleNote GPS: A Training Guide; consequently, I decided to review both the product and the tutorial together. (It should be pointed out here that Michael May is listed as an editor on the acknowledgments page of the guide, indicating that the De Witt and Associates editors, Kay Chase and Richard Fox, clearly collaborated with and received approval from the Sendero Group.) De Witt and Associates' courseware materials are available in print, braille, DAISY, and text CD formats. The braille and print versions are both spiralbound. The braille is in four small (8.5 by 11-inch) easily handled volumes and was the version that was primarily used for this review.

In its promotional literature, De Witt and Associates says that its aim is to enable assistive technology trainers and training centers to provide consistent training experiences. The quality of these materials will definitely help ensure that consistency. Although the guide's target audience is instructors, it can also be used by individuals who are teaching the software to themselves.

The material is divided into 11 lessons that are arranged in a logical progression. Each lesson contains learning objectives, a list of terms that are used, shortcut keystrokes for both the BrailleNote BT and BrailleNote QT (these are models with a Perkins-style braille keyboard and a QWERTY keyboard, respectively, so that keystrokes are often different), handouts and activities for students, and an assessment tool for measuring students' progress. Lessons are clearly and concisely written. Each segment of each lesson is short enough that it is easy to locate desired material for a reference point when you are working outside the sequential lessons format.

Planning Routes

With the BrailleNote GPS, you can sit in your office or living room and plan a route for walking or driving anywhere within your state. Similarly, if you are planning a trip to another state, you can load that state's map and plan routes to already-known addresses or use the POI database to determine which tourist attractions, hotels, or restaurants you may want to visit while in the area. One particularly helpful feature is that you can set any address as a starting point and another as your destination and thus determine the distance between two places before you actually set out on your walk or drive.

With the De Witt tutorial, learning the many, varied, and rich features of the Sendero GPS software is a fairly easy and straightforward process. Lessons literally have you walk before you run (or, in this case, "ride" in a rapidly moving vehicle) and, in fact, instruct you to practice some of the techniques in a quiet place before you venture outdoors.

Saving Routes

If you want to plan a route for walking or driving, the tutorial shows you how. You can then examine the route waypoint by waypoint or turn by turn. Reading the route from waypoint to waypoint is an extremely detailed, sometimes tedious, mode of examination, while putting the unit in Turns mode enables you to examine the actual route itself—much like the directions obtained from MapQuest or other online mapping services. Routes can easily be saved to be called up at a future time for study or following. Unlike some GPS products, the Sendero GPS makes a clear distinction between pedestrian routes and vehicular routes. In other words, it will not direct you to walk up the ramp to the freeway.

One of my favorite exploits with the Sendero GPS—one that is not really addressed in the tutorial—was simply to "walk around" a map while in Virtual mode. I went to my childhood hometown—a place that I have not been to since high school—and put in the address of the home where I lived as an adolescent. From there, I "walked" the route to my high school, discovered that my favorite ice cream shop is still listed as a POI, and was surprised to learn that a good friend who seemed to live far away in my childhood really lived only 9.97 miles from my family's home. I did all this while I was sitting in a comfortable chair and using simple keyboard commands to go left, right, or straight, with the software telling me all the while the names of intersections, announcing every church and pub and barbershop along the way, and even telling me when a street came to a dead end. At various points, I could check the distance to see how far I had "walked" or how far there was yet to go. The pedometer, in either pedestrian or vehicular routes, can be reset to zero at any time in either the Virtual or the GPS mode. (The GPS mode may be thought of as "live" mode, that is, when the receiver is activated and satellites are detected.) In either mode, you can ask for the current direction of travel. Of course, certain information is available only in the GPS mode—the speed at which you are traveling, for instance, the number of satellites that are currently detected, or the altitude of the current location.

With the Sendero GPS, you can record your own POIs, which can mean that the heretofore inaccessible freedom of traveling without sidewalks is now possible. You can record a tree, a park bench, or a playground swing set as a POI and, with the GPS software guiding you, come within 30 feet of the designated spot. Often, the distance is even more accurate.

Glitches

Sometimes, the maps are wrong. Minor examples may be that while your town calls a particular route High Street, the GPS maps refer to it as Highway 65. Or maybe your GPS identified Andy's Book Shop at the corner of Main and Maple, when you know (or find out by traveling there) that it was sold last year and is now Maria's Beauty Salon and Spa. Slightly more aggravating errors are when the system simply does not recognize an address that you know exists. For instance, the street where my doctor is located did not go beyond the 5500 block in the GPS maps, although her address is 7710. At another time during this review period, while planning a college visit for my daughter, I discovered the absence of an entire town! Still, with a little creativity, there are work-arounds for such problems. To map a route to the 7700 block of the street that would not allow me to go beyond 5500, I asked the system for POIs within two miles. From the 50 categories, I chose Medical. Then, when my doctor's name came up, I marked it as my destination. The system then accurately mapped the route. Similarly, to find the way to an address in the unnamed town, I went to a nearby town and searched for POIs within 5, 10, and 15 miles. All the POIs and streets of the unnamed town were actually there, and the resulting routes, with this work-around, were reliable.

Charles LaPierre, chief technology officer of Sendero Group, the man who wrote the software for the Sendero GPS, informed me that many of these problems are with the maps themselves, provided by Tele Atlas, and that many such errors will be fixed in this year's release. He also indicated that one future plan is to enable a user to search within a specified zip code, which will provide another work-around for locating items that are omitted in the map.

Errors in the De Witt and Associates tutorial were negligible—a few typos or braillos and, in one instance, two pages out of order—but, overall, the materials are extremely well organized, professionally presented, and thorough. When you are searching for POIs in a given area, you can select "All" and read all the POIs in the area or select 1 of the 50 categories. If you press Enter, the entire list is presented. The tutorial instructs that if you know the name of the desired POI, you can enter the first three letters and be presented with all the names that contain these letters. What it does not tell you is that you can also enter the entire name if you know it and thus quickly locate the desired landmark.

The Bottom Line

The Sendero GPS software for BrailleNote products is a wonderful navigation aid and resource for computer users who are blind. It is the oldest GPS tool in the assistive technology market, developed primarily by people who are blind, and thus has addressed many of the issues that other tools still face. It has some minor flaws, but its overall usefulness far outweighs their significance. Many people have reported that they purchased this software but did not use it, fearing that the learning curve would be too great. The De Witt and Associates training guide has organized the learning steps in such a friendly and facile manner that learning should no longer be difficult for anyone who is able to operate a BrailleNote and who has appropriate mobility skills.

GPS software is intended for navigation, wayfinding, and identifying landmarks and street names. It should not, however, be viewed as a replacement for the traditional mobility tools of a dog guide or a white cane. Happily, the De Witt and Associates tutorial emphasizes this point and other safety precautions repeatedly. The BrailleNote GPS can tell you which streets to walk and when to turn to arrive at a never-before-investigated Italian restaurant, but only the proper use of a white cane or a dog guide can tell you if there is an open hole in the road, a construction site, a low-hanging branch, or another obstruction along the way. Only the use of orientation and mobility skills can tell you if the street can be safely crossed. With this caution in mind at all times, the Sendero GPS software is a remarkable enhancement to independent travel if you are blind, and the De Witt and Associates tutorial enhances the teaching or learning experience.

Manufacturer's Comments

The Sendero Group

"In addition to what you have read in this article, the Sendero GPS has powerful manual route-recording features that enable you to plan custom routes across campus or off-road in the woods. We have acquired databases of bus stops for three cities so far, as well as for talking ATMs for three bank organizations. Users are sharing thousands of personal points via the Sendero web site.

"After 12 years working on accessible GPS, we are pleased that the technology has come so far, from 12 pounds to 1 pound. At the same time, as the article points out, there is room for improvement in the Sendero software, with GPS and map accuracy. Our map and GPS hardware suppliers are constantly improving their part of the equation. Sendero will continue to implement changes that hundreds of blind users request, as well as to develop new wayfinding technologies for outdoor and indoor environments."

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Product Information

Product: BrailleNote GPS.

Manufacturer: GPS software: The Sendero Group, 1118 Maple Lane, Davis, CA 95616-1723; phone: 530-757-6800; e-mail: <gps@senderogroup.com>; web site: <www.senderogroup.com>.

Manufacturer: BrailleNote: HumanWare, 175 Mason Circle, Concord, CA 94520; phone: 800-722-3393 or 925-680-7100; e-mail: <info@humanware.com>; web site: <www.humanware.com>.

Price: $1,599, for version 3.5 with a 1-GB compact flash.

Manufacturer: Teaching and Learning the BrailleNote GPS: A Training Guide: De Witt and Associates, 700 Godwin Avenue, Suite 110, Midland Park, NJ 07432; phone: 201-447-6500 or toll-free 877-447-6500; e-mail: <sales@4dewitt.com>; web site <www.dewittassociates.net>.

Price: $129.

Reading by Hand: A Review of the Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader

The world's first handheld optical character recognition (OCR) reading system, the Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind (NFB) Reader (hereafter, the Reader), was released to the public on July 1, 2006. This innovative new technological device combines a digital camera and a personal digital assistant (PDA) to capture the image of printed text and translate it into synthetic speech. This article presents the results of our evaluation of the device at the AFB TECH product evaluation laboratory. Before presenting the results, though, I will briefly discuss the collaboration between renowned inventor Ray Kurzweil and the NFB to bring the Reader to market.

In 1975, Kurzweil (who was interviewed in the September 2004 issue of AccessWorld) unveiled the Kurzweil Reading Machine, which was the first multifont OCR system that was capable of converting printed text to synthetic speech. The original machine was a large stand-alone unit that has been described as being the size of a small washing machine. Priced at $50,000, its cost was out of the reach of individual consumers.

Over the three decades since the release of the Kurzweil Reading Machine, OCR technology has evolved considerably. It now runs on PCs that are equipped with inexpensive off-the-shelf scanners, and the leading consumer OCR software products for people who are blind cost just under $1,000. (Our latest evaluations of these leading software products, the Kurzweil 1000 from Kurzweil Educational Systems and OpenBook from Freedom Scientific, appeared in the July 2006 issue of AccessWorld.) The Reader takes this evolution one step further by putting the technology into a portable device that can be taken anywhere.

Developing the Reader

The Reader is the result of a collaboration between NFB and Kurzweil, each of whom contributed their own unique strengths to the development process. Kurzweil brought his obvious technological expertise and history of accomplishment in the technological world. In addition to inventing the Kurzweil Reading Machine, he is also credited with inventing the first text-to-speech synthesizer; the first music synthesizer that is capable of re-creating orchestral instruments; and the first commercially marketed, large-vocabulary speech-recognition engine. In 1999, Kurzweil received the National Medal of Technology, the nation's highest honor in technology, from President Bill Clinton in a White House ceremony. In addition to providing considerable financial backing for the venture, NFB was deeply involved in the design of the user interface and in managing the project.

NFB also provided its greatest resource: its membership. As many as 500 NFB members participated as so-called Reader Pioneers in an extensive beta-testing process, providing invaluable input to the engineers as they refined the product. I was fortunate to be one of the beta-testers, which provided a great resource for this article. The Reader Pioneers were all connected via an extremely active electronic discussion group, so users' tips and techniques were readily available. What is more important, key members of the design team were also part of the discussion group, so they received immediate feedback that could be incorporated into the current and future versions of the Reader. The design team also collected all the images that the Reader Pioneers captured and the resulting documents, so they could be analyzed for the Reader's future development.

Product Description

The Reader weighs 15 ounces and measures 6 inches long by 3 inches wide by 2.5 inches deep. As a point of reference, it is 1,000 times smaller than the original Kurzweil Reading Machine, and its processor is 2,000 times faster. Its price ($3,495) is about one- fifteenth the price of the original. The Reader currently consists of a Fujitsu-Siemens LOOX N560 PDA and a Canon SD20 digital camera that are housed in a leatherette carrying case, which also houses the electronics connecting the two units.

The heart of the system is the OCR software that converts the camera image into synthetic speech. Because this software has to process a captured image from a digital camera, rather than from a flatbed scanner, it is completely new and different from the OCR engines that are used in traditional OCR software products. The system uses the Eloquence speech-synthesis software that is familiar to users of screen readers for PCs and cell phones, and you also have the option of using the RealSpeak synthesizer. The Reader also comes with a small canvas carrying case, about the size of a small lunchbox, that has pockets for all the accessories, such as the AC adapter/battery charger for the PDA, battery charger for the camera, headphones, and memory cards. The Reader comes with a year of software upgrades and a one-year warranty. No hardware upgrades are included.

Caption: The Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader comes with a carrying case, software, and documentation in print and on CD.

When you hold the unit in what the manual calls the normal position, the display screen and control panel face up toward the ceiling, with the control panel closest to you. The control panel is a rectangular area with nine buttons. In the center of the rectangle is a five-way navigation control that may be familiar to users of cell phones. It features an Enter button in the center, surrounded by four arrow buttons that point up, down, left, and right. To the left of those five buttons are two function buttons, F1 and F2, and the F3 and F4 function buttons are to the right of the five-way control. Moving toward the back of the top panel, you will find the 3.5-inch visual display screen, which is protected by a thick plastic covering. The small front panel facing you has just one control, a large button on the right side that is used to reset the unit. On the back panel facing away from you, you will find the memory-card slot and the headphone jack. The only thing on the left side panel is the jack for the AC adapter, and there is nothing on the right side panel.

Caption: The top of the Reader showing the control panel and display screen.

The camera is attached to the back end of the bottom of the PDA and has an auto-focus lens pointing down toward the target document. The lens is protected by a mechanical door that automatically opens or closes when the camera is on. It has two buttons on the left side panel. The large smooth button near the back is not used, but the smaller button, which is flush to the panel and rough to the touch, is the camera's On/Off button.

How Does It Work?

Although I will not bore you with all the details, I want to give you a general idea of how to use the Reader. Those who want all the details can go to the web site <www.knfbreader.com> and download the manuals and other documentation. The NFB staff wrote the documentation and an accompanying tutorial. The basic process of capturing and reading an image is relatively simple, and voice feedback guides you along the way when you use the Reader. You press the F1 button, followed by the F2 button, to power on the PDA, and you are almost immediately told that the unit is on. You then turn the camera power on and hold the Reader with the camera pointing down about 16 inches above your target. Next, you press the down arrow and hold the unit steady until you hear the camera's shutter click. You then hear progress tones and voice prompts as the image is processed, and in about 30 seconds, you begin to hear the voice reading your document. The Enter button can be used to start and stop reading your document. This is, of course, just a simplistic description of how to use the Reader, and there are several other features and functions, some of which are discussed next.

Features and Functions

Changing Modes

The Reader has three modes, and pressing the F2 key cycles through them. The Shooting mode captures images. The User Settings mode is used to configure many of the Reader's settings, such as the time and date, whether or not files are saved automatically, and how columns of text are handled by the Reader. Finally, the Document Reader mode controls how the left and right arrows can be used to navigate through documents. For example, you can set the Reader so the arrows move by line, by word, or by sentence. The Document Reader mode also controls the speed and volume of the speech output.

Field of View Report

Properly aiming the camera at your target is the hardest thing to master. To help you along as you practice, the Reader has a Field of View Report that tells you how well you are aiming. When you think you have aimed correctly, you can press the up arrow, and a preliminary picture is taken without using the flash. In about three to five seconds, the Field of View Report tells you how many edges of the target document are visible and what percentage of the page contains text. You can adjust your aim accordingly. For example, if you hear, "Top bottom and left edges are visible, 40% full," you may want to aim a bit more to the right to capture the document fully. Your goal is to hear the Reader say, "Portrait orientation, 70% full."

View Finder

The View Finder, another tool to help with aiming, is useful to a person with some functional vision. While in the Shooting mode, you press the F3 button, and an image of the target appears on the display screen. If you can see four edges, you are ready to take the picture.

File Explorer

The File Explorer application, which can be accessed in the Document Reader mode, can be used to view and arrange folders and files that have been saved on the Reader. In addition, you can open documents that you previously saved and begin reading them in the Document Reader. You can also use the File Explorer to open documents that you have moved to the Reader from your PC using the memory cards.

Voice Notes

You can use the Reader to record short memos or sound clips up to 30 seconds in length. You can also associate a recording with a certain file. This is a particularly useful feature for naming files because you cannot type in your own names for files that you are saving. Because the Reader has no keyboard for typing in file names, it simply uses the current date as the file name.

Help

The F1 key is the Help button, and it works like the keyboard help on the screen readers and PDAs that are familiar to many people who are blind or have low vision. You press the Help key, followed by any other button, and the Reader tells you the function of that button as it relates to the mode you are currently in, which is important because each button's function can change, depending on the current mode or task. Pressing the Help button twice gives you the status of the batteries for the PDA and camera.

How We Evaluated

As with all the products we evaluate at AFB TECH, we examined the Reader from many perspectives. We looked at the tactile nature of the interface, as well as the quality and responsiveness of the audio output. We tested the battery life and available documentation and considered the device's overall ease of use. Finally, we tested the accuracy of the device using a variety of text styles and colors and in various settings. In addition, AFB TECH had a summer intern program of high school students who are blind or have low vision from the Huntington, West Virginia, area, sponsored by the Reader's Digest Partners for Sight Foundation, who worked on projects that evaluated a wide range of assistive and mainstream technological devices, including several cell phones, diabetes devices, and copy machines. These interns were able to use the Reader and give us their feedback.

Caption: High school interns helped test the Reader at AFB TECH's lab.

Results of the Evaluation

The Interface

The Reader has an accessible interface. Although some people may have initial trouble identifying and using the control buttons, most people who have had experience using technological devices and gadgets should find the buttons easy enough to identify and use. Some people may wish that the Reader had larger control buttons, but larger buttons would probably lead to a larger, less portable, device. All the tasks can be accomplished independently, including charging the PDA and camera batteries and replacing the camera battery, and high-quality voice prompts guide you along the way. The speech produced by either the Eloquence or RealSpeak synthesizers is responsive to users' keystrokes. The design team did a great job of creating an extensive user interface with a great deal of functionality, considering that the PDA has only nine buttons. Although mastering the unit may seem a bit daunting at first, it is actually fairly intuitive, and the documentation and help system can get a new user up and reading in a relatively short time. One limitation of the hardware is the volume level produced by the built-in speakers. It is sometimes not loud enough in certain situations, such as at a busy airport or a noisy restaurant. Using a headset improves the volume output, and some people are using small wireless Bluetooth speakers for louder output, but doing so slightly reduces the unit's portability. A Bluetooth earpiece would be a less bulky solution and would give you more privacy.

Documentation

The documentation is accessible, informative, and available in a variety of formats. The User Guide, Quick Start Guide, Frequently Asked Questions, and Key Command Summary all come in accessible RTF or PDF formats for reading on your PC or PDA and are built in to the Reader itself. Each is also available in print and braille and in an audio tutorial on a CD. This documentation is more than sufficient to get a new user started, and the detailed instructions are aimed at people who are blind or have low vision.

Battery Life

If you press the F1 key twice, the Reader will respond with the percentage of battery life remaining in the PDA and camera batteries and will speak a low-battery warning if either battery is getting low. It takes about two hours to charge the PDA battery, and you get various amounts of use out of one charge, depending on how much you are using the unit. While we were testing and using the Reader extensively, we got about one full workday out of a charge, and when we were not using the unit at all, we got about three days out of a charge, since the battery drains even when the Reader is not in use. The User Guide recommends that you leave the PDA connected to the charger overnight or when it is not in use. The camera battery takes about 90 minutes to charge, and an extra battery is provided, along with an external charger, so you always have a fresh one ready. We got 85 to 105 pictures out of a charged battery before we needed to change it. Changing the camera battery can be a bit tricky, so you should consult the User Guide for instructions. You need to be sure to keep the PDA and camera securely together when you change the camera battery.

Overall Ease of Use

Although you have to read the documentation and practice using the Reader to get accustomed to using the buttons to control all the features, it is not difficult to learn how to use the Reader. Aiming is the biggest challenge that faces new users, and we found that with practice, it is possible to learn to aim the camera properly. The Field of View Report and View Finder tools were helpful while we were learning to aim, but we rarely used them after we got the hang of aiming. Some people who have trouble keeping the Reader steady may want to brace their arms against something when aiming. The high school interns were quick learners. We spent an afternoon with them playing the audio tutorial and giving them a brief training session. All were then easily able to work with the Reader for the next two days testing various print documents, and they even helped give a demonstration to a local rehabilitation agency.

Low Vision Accessibility

Although this device is mainly a tactile and auditory experience, we also examined it from the perspective of a person with low vision. The buttons are the same color as their background, so most people with low vision will have to rely on tactile rather than visual techniques to identify the buttons. The View Finder helps with aiming, but the distortion caused by the thick plastic cover can detract from the effectiveness of that feature for some people with low vision.

Accuracy

Here are the results of our testing of the accuracy of the Reader on several different types of print materials and the interns' ratings of accuracy on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being least accurate and 5 being most accurate.

Simple Black-on-White Text

We found a high level of accuracy with this basic type of document. The Reader accurately recognized nearly all such documents, performing as well as the Kurzweil 1000 or OpenBook would perform on a PC and scanner system. The interns rated the accuracy as 5.

Caption: The interns rated the Reader highly accurate in reading simple black-on-white text.

Multiple Columns

We had less success reading print in multiple columns, such as those in a newspaper article or a utility bill. Changing the setting that is used to adjust how columns are handled helped, and with practice and persistence, the information captured was usually read. The interns rated the accuracy as 4.

Caption: Reading print in columns was more difficult.

Bold Print

The Reader read bold print well, perhaps even better than it read normal print. The interns rated the accuracy as 5.

Italic Print

The Reader was less successful with italicized print. The interns rated the accuracy as 4.

Mixed Fonts and Sizes

The Reader performed well on documents with mixed sizes and fonts of text. It did not have trouble with the changing print. The interns rated the accuracy as 5.

Documents with Colors and Images

The Reader had a great deal of difficulty in this area. White print on a dark blue background was a problem; the Reader recognized little or no text. The interns gave this aspect of the test a rating of 2. The Reader did slightly better when we tested it with various colors on a white background, earning a rating of 3, but yellow was particularly troublesome. The Reader did better with documents containing photographs or other images. For the most part, it ignored the images and properly read the text, earning a rating of 4.5.

Reading a Large Sign

We used the Reader to read a large (3 foot-by-2 foot) sign in the lobby of our building, but we did not have much success, and our interns gave this aspect of the text a 2.5 rating. In general, text that is larger than about 48 points is often difficult for the unit to read.

Reading Product Packages

The Reader's performance when reading product packages was a mixed bag. We had less success with round containers like soup cans than we did reading the baking instructions on a flat box of brownie mix. Flat packages were read well if they did not have a lot of color or stylized images on the labels, but round containers often required a lot of trial and error, and we often resorted to cutting the label off some cans. Overall, the Reader received a rating of 3.5 in this area.

Reading Miscellaneous Print

One of the most intriguing things about the Reader is its ability to provide access to print that you encounter in everyday life. As long as the text is not too colorful, the Reader usually does a good job of recognizing and reading. It is useful in sorting mail, reading receipts and bills, and reading handouts in a classroom or conference. We testers had a wonderful feeling when we read a menu at a restaurant independently instead of bothering our dinner companions or waiters. We AFB TECH lab rats even finally figured out what all the hotel room information sheets said when we were on the road at a recent conference!

The Bottom Line

The Reader is a big step in the evolution of OCR technology and has the potential to give those who use it a great deal of independence. The interface is accessible, and the documentation provides the tools that are necessary to learn all the ins and outs of using the unit. You will also find that, with some practice and persistence, you can master the technique of properly aiming the Reader. The Reader accurately reads black print on a white background, but has some problems recognizing colored text or text on a colored background, especially when yellow is involved. It is certainly portable, especially when compared to traditional OCR technology, but it is still not quite as convenient as slipping a cell phone into your pocket. The Reader is not yet as accurate as the traditional Kurzweil 1000 or OpenBook OCR systems, but it is not far behind.

The Reader has received a great deal of national media coverage. While this coverage has been mostly positive, some commentators, including the Wall Street Journal, have winced at the $3,495 price tag. This is certainly a great deal of money for many of us, but it is not out of the cost range of other assistive technology devices that we use. Considering that a PC that is equipped with a screen reader costs about $2,000 and a PDA with a braille display costs about $5,000, the Reader has a mid-range cost. Also, the Reader is now being offered with an introductory $200 discount, lowering the cost to $3,295. Nonetheless, it is a big purchasing decision, and you should consider how the Reader fits your budget and reading needs. You will want to do research and, if possible, talk to others who have used or own a Reader. You can read more about the Reader at the web site <www.knfbreader.com>.

On the Horizon

The K-NFB Reader is certainly a one-of-a-kind product, and we have seen no competing products on the horizon. The manufacturers are continually working on improvements and will periodically release updated versions of the software, continually improving its accuracy. They are also testing more and more hardware solutions, and the device will eventually evolve into a one-piece unit that is smaller and even more convenient as the mainstream technology on which it is based continues to evolve. Over the next few years, we may see the Reader software on a cell phone when the cameras on cell phones get more powerful and become equipped with an auto-focus feature. We may also see a unit with the capability of running other access software, such as a cell phone screen reader or a pocket PC screen reader, to provide access to many of the other PDA or cell phone features.

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Product Information

Product: Kurzweil-National Federation of the Blind Reader.

Manufacturer: K-NFB Reading Technology; web site: <www.knfbreader.com>. For a local dealer, contact Kurzweil Educational Systems, 100 Crosby Drive, Bedford, MA 01730; phone: 800-894-5374 (press option 4 for customer service).

A list of dealers is provided on the web site <www.knfbreader.com/sales.html>. You can also contact National Federation of the Blind, 1800 Johnson Street, Baltimore, MD 21230; phone: 410-659-9314; web site: <www.nfb.org>; Tech Support e-mail: <readerhelp@nfb.org>

Price: $3,495 plus $50 shipping (an introductory price of $3,295 is available only by calling NFB at 888-708-1724).

This product evaluation was funded by the Teubert Foundation, Huntington, WV. We would like to acknowledge the research assistance provided by our Reader's Digest Partners for Sight Foundation interns: Aaron Preece, Patrick Barbour, Brandy Jacobs, and Eric Dowdy.

The Mosen Excursion

When news of one man's job change hit the e-mail lists on September 1st, the blindness technology grapevine zoomed into hyperactive gear. For three years, Jonathan Mosen has been product manager for HumanWare's BrailleNote family of products. On September 1, Freedom Scientific announced that he will now be working for them as vice president of blindness hardware products. That means, in effect, that after promoting one braille personal digital assistant (PDA) for three years, he will now be promoting its best-known competitor.

Debates arose on e-mail lists about BrailleNote vs. PAC Mate, closed system vs. open platform, and whether or not customers should question Mosen's integrity. "Did I buy the wrong PDA?" blind customers were asking. "Will the BrailleNote still be developed?" "Does he really think the PAC Mate is a better product?" And so on.

Why so much interest in one man's move from one company to another?

While this kind of move might attract attention in any industry, there are some details specific to blindness that fueled the initial furor.

There's the limited access to products, for one thing. People who are blind can't drop in at the local Circuit City to fiddle with the laptops or PDAs on display before getting out their credit cards. Instead, we look for reviews in AccessWorld, listen to related Internet broadcasts, or subscribe to e-mail lists where users are discussing products of interest.

Although Jonathan Mosen has only been in the assistive technology field for three years, many Internet radio enthusiasts who are blind or visually impaired were familiar with his voice and his name for three years prior to that. As founder and first director of ACB Radio in December 1999, Mosen's voice could be heard by people who are blind around the world. Later, through his Internet program and blog, both called the Mosen Explosion, those tuning in could learn about his political views, musical tastes, technological savvy, and a host of other personal and professional details.

Just as sighted consumers identify with visual images--the face of a certain executive or an icon representing a product--people who are blind have a similar recognition linked to sound cues (like a song or a person's voice.) Then, add to our affinity for the audibly recognizable the fact that Mosen is from New Zealand. (We Americans have an exaggerated fascination with foreign accents--particularly those from other English-speaking countries. A pedestrian pronouncement seems somehow more sophisticated when we hear it spoken by someone from London, Sydney, or Christchurch than, say, Pittsburgh or Sacramento!)

BrailleNote customers heard Mosen's voice on tutorials, too, and at conferences and conventions. They came to identify him with the product he sold.

HumanWare (formerly Pulse Data) and its KeySoft system have been around for more than 20 years--begun, in fact, before the young Mosen's voice would have been changing. Whether or not its development will be ongoing, in other words, probably depends far more on its creator, Jonathan Sharp, and other HumanWare development team members, than on one former employee who loved and used it and brainstormed ways to improve it.

Why, then, were the concerns for the future of the company disproportionate to Mosen's role? Certainly, his high visibility (or audibility) in the blind computing community had something to do with it. People came to know him through his broadcasts and blogs and e-mail messages. (He says, incidentally, that he won't be doing any Internet radio now, and his blog has been closed and removed from the Web.)

But words like loyalty and betrayal don't come up just because someone whose voice you recognized changes jobs. No, the emotional level of trust and interest are tied, I think, to something far more basic. There is a serious marketing lesson here for any company hoping to sell products with large price tags to consumers who are blind. Customers who are blind feel a special kinship with Jonathan Mosen because they have come to know him, yes, and because they like his accent, yes, and because he knows a lot about technology. Mostly, though, people care so much about one man's job change because Jonathan Mosen is one of us: He is blind.

AccessWorld News

Congratulations, Jim Fruchterman

On the cover of the November 2001 issue of AccessWorld was a photo of Jim Fruchterman, CEO of the Benetech Initiative, heralding the article "Fruchterman Fantasy Becomes Reality." Known to many in the assistive technology field as early as 1989, when his newly founded company Arkenstone brought the first computer-based scan-and-read system to people who are blind with OpenBook, he had moved on by 2001 and was about to launch yet another Fruchterman brainstorm. Bookshare.org, the web-based system, in which users who are blind or otherwise print disabled share books with all other members, was another Fruchterman idea that has become a familiar name to most blind computer users. We called him a genius then, and the MacArthur Foundation apparently agrees.

As one of 25 winners of the 2006 MacArthur Fellowship from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Fruchterman will receive a "no strings attached" $500,000 grant over the next five years. What new projects the electrical engineer and social entrepreneur has in store remain to be seen. One futuristic gadget that was particularly appealing in the 2001 interview in AccessWorld was what we dubbed a People Finder: It was technologically feasible, Fruchterman then said, to develop a gadget that could tell a blind person who else was in a room or at a ball game. By now, his fantasies may be even more surprising. We look forward to seeing what this well-deserved accolade helps Fruchterman bring into being.

Notetaker Trade-in

In the first two weeks of September, the noisiest buzz in the world of assistive technology was sparked by the news that Jonathan Mosen, the former product manager of HumanWare's BrailleNote, had moved to Freedom Scientific as vice president of blindness hardware products (see "The Mosen Excursion" in this issue). Just as interest in that item was waning, Freedom Scientific circulated another surprising announcement: Owners of any BrailleNote product are invited, for the remainder of 2006, to trade in those units for its leading competitor, the PAC Mate, at a savings of 60 to 70 percent. In what Freedom Scientific is calling its Open Plan, any BrailleNote product in good working order—BrailleNote, VoiceNote, BrailleNote PK, or BrailleNote mPower—is included in the trade-in program. The promotion focuses on the different approaches taken by the two companies: BrailleNote products offer a "closed" architecture, which is designed specifically to enable users who are blind to work in the familiar KeySoft environment, and PAC Mate products offer an "open" platform that runs mainstream applications. Although each model of PAC Mate is discounted, the offer makes no allowance for the different values of BrailleNote products (which range in price from $2,000 to $6,000).

The three options are as follows: Trade in any BrailleNote product for a speech-only PAC Mate BX400 or QX400 for $700, trade in any BrailleNote product for a 20-cell PAC Mate for $1,500, or trade in any BrailleNote product for a 40-cell PAC Mate for $2,250.

For more information on the Open Plan, contact Freedom Scientific: phone: 800-444-4443; web site: <www.freedomscientific.com>. For more information on the BrailleNote family of products, contact HumanWare: phone: 800-722-3393; web site: <www.humanware.com>.

New Ownership of Ai Squared

For almost 20 years, Ai Squared has been a well-known company in the assistive technology field, developing products for people with low vision. Its flagship product, ZoomText, is a screen-magnification program with speech options that enables people with low vision to see and hear a computer screen in a wide range of popular applications.

The company was recently purchased for $22 million by Technology Investment Capital Corporation and a private investor. Except for letting us know how much one popular company in the assistive technology field is worth, the transaction appears to have little, if any, impact on Ai Squared's intention to pursue business as usual. For more information on Ai Squared and its products, visit <www.aisquared.com> or phone 800-859-0270. For more information on Technology Investment Capital Corp., visit <www.ticc.com> or phone: 203-661-9572.

DAISY Notes from HumanWare

In two announcements that were issued within a week of one another, HumanWare U.S. and HumanWare Canada released DAISY-related news to the assistive technology marketplace. HumanWare Canada (formerly VisuAide) has long been known for its leading DAISY CD players. Now, the company has replaced its Victor Reader Classic desktop player with the new ClassicX and ClassicX+ models. The improved players boast a better battery performance, higher color contrast of keys, a sleep timer, and more easily distinguishable AC power and headphone jacks. These DAISY players enable the listener to navigate an audio book or magazine in much the same way that a print reader does—jumping easily from page to page or chapter to chapter, setting bookmarks, and easily searching for desired information.

From the U.S. division of HumanWare, best known for its BrailleNote family of products, has come the news of KeySoft 7.2, an upgrade available for all BrailleNote products that, along with enhanced file management and e-mail capabilities, now offers users DAISY players in their BrailleNote or VoiceNote units.

For more information on the Victor Reader ClassicX series, contact HumanWare Canada at <www.HumanWare.ca>, phone 450-463-1717. For more information on KeySoft 7.2 and the new Daisy player, contact HumanWare U.S., web site: <www.humanWare.com>; phone: 800-722-3393.

Talking Books on the Go

A September 19 article from Korea Times reported the availability of a new mobile phone from LG Electronics that was designed specifically to benefit people who are blind or have low vision or dyslexia. The LF1300 allows South Koreans to download Talking Books either to their computers for transferring or directly to the mobile phone itself. Described as a state-of-the-art phone, the LF1300, which comes with a Bluetooth headset for wireless talking and listening, is also an MP3 player for listening to music and can be operated with voice commands. At this point, AccessWorld has been able to obtain no information on its availability in other countries. The LG Electronics web site is <www.lge.com>.

Legends and Pioneers of Blindness Assistive Technology, Part 3

This is the third in a series of articles on the history of blindness assistive technology, gathered from interviews with 25 of the giants who created that history. In Parts 1 and 2 (in the July and September 2006 issues of AccessWorld), I described the conceptualization of the project, the methods I used to select the interviewees, and the nature of the oral history process. I then summarized the interviews that I had conducted for this project. In this article, I present a short historical tour of the technologies that were the precursors of modern blindness assistive technologies and place the legends and pioneers whom I interviewed in the context of that history. I also include some of their comments from the interviews.

A Brief Time in History

Except for the first use of a tree branch to fashion a crude cane and the fashioning of the first optical aids about a millennium ago, almost everything there is to report about the history of blindness assistive technology has taken place in the past 200 years. Moreover, the development of electronically based technologies for people who are blind or have low vision began only 50 years ago, finally being put on the market in the 1970s.

Arguably, the first "technology" that was developed for people with low vision was the magnifying lens, and the first technology that was developed for people who are blind was braille. According to the Inspiration Line Trivia and Facts web site <www.inspirationline.com/Brainteaser/eyeglasses.htm>, the first eyeglasses (about A.D. 1000) took the form of handheld lenses. Head-borne eyeglasses were probably invented by an Italian monk, scientist, or craftsman about 1285, and when Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1456, which made printed books accessible to more people, the evolution of eyeglasses was fully launched. Today, sophisticated lens-manufacturing techniques and modern optometry have combined to produce a wide variety of differently shaped lenses to correct errors of refraction or to redirect light in ways that help the human eye better apprehend the visual world.

It was not always this way. When Sam Genensky, inventor of the closed-circuit television (CCTV; also known as a video magnifier), was a boy in the 1940s, he had a powerful pair of binoculars adapted, so he could use his one good eye to look down the left side to read books and down the right side to see the chalkboard. Genensky eventually earned a doctorate in mathematics. At that time, William Feinblum had not yet developed the first low-vision lenses.

According to the Television History web site <www.tvhistory.tv>, the period 1946-1949 saw an explosion in the purchase of television sets by the general public, but it was the following decade that witnessed the birth of color television, the remote control, and interesting uses of the transistor. It was during this time that the technology that was used in the first CCTV-video magnifiers reached maturity. In the late 1950s, John De Witt, founder of the De Witt and Associates assistive technology company, saw a prototype developed at the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB), but its quality was poor. As he put it in an interview with me, "It was this rather grainy, not high-contrast, print on the television screen, a black print on a somewhat flickery white background . . . sort of distorted at the same time. But that was real early stuff." Ten years later, Genensky, working for the RAND Corporation, developed the first marketable CCTV. Genensky, in a letter to me on October 9, 2006, explained, "What was done by AFB was the design and testing of a projection magnifier that did not involve the use of television equipment (i.e., a TV camera and a TV monitor). The projection magnifier was similar to a microfiche reading device."

Since then, we have seen the development of small and large television sets, movement away from old-style cathode ray tubes to plasma and high-definition screens, and revolutions in cameras leading up to today's modern imaging technologies, such as that in HumanWare's myReader device, which, as Russell Smith described it to me, is "a system that will capture the entire page in one shot, will analyze the page to recognize where columns and pictures are, and will reformat the text so it fits across the width of the screen. You can read down the screen, and you can have the text rolling vertically as it does on a teleprompter."

The Tactile Revolution

According to the history of braille provided on the Enabling Technologies web site <www.brailler.com/braillehx.htm>, Valentin Haüy founded the first school for students who were blind in France in spring 1784. In 1819, when 10-year-old Louis Braille became its youngest student, the school had 130 pupils and 14 books hand-embossed with natural lettering. It is likely that the paucity of accessible educational materials, together with a tactile code introduced to him by an artilleryman, Charles Barbier de la Serre, inspired Braille to invent the system that bears his name. In October 1824, Braille unveiled his code. He had found 63 ways to arrange a 6-dot cell, a remarkable improvement on the 12-dot cell code that had failed to work for the French army in its attempt to develop a night-reading method for its troops.

Meanwhile, in 1808, the first typewriter, the piston board, was invented for an Italian countess who was blind, so she could write legibly for sighted readers, but it was not until the 1870s that typewriters were widely disseminated. In between, movable blocks were used to print braille books. Although the technique was tedious, it was not too different from the way print books were produced (hence, the term "braille press" used by organizations that produce braille, such as National Braille Press). In the 1890s, an interpoint technique was developed to save paper by allowing braille to be printed on both sides of a page.

According to the January 2005 issue of InTouch, the e-newsletter from Optelec USA's Blindness Products Division, the Perkins Brailler was invented in 1941 by David Abraham, a skilled craftsman who was employed by the Perkins School for the Blind. In 1969, the first prototype braille display was developed by Argonne National Laboratory, the first embosser for regular braille pages was developed at MIT (by George Dalrimple), and the Braille Authority of North America was established. Joe Sullivan, of Duxbury Systems, described the first embossers produced by the Mitre Corporation in concert with MIT: "They had previously done what you might say were Teletype-like things. They would put braille into a strip tape (an adapted Teletype). The Braille Emboss was the first thing that I know of . . . that did a page of braille."

In the 1970s, the American Printing House for the Blind (APH) and then Duxbury Systems began to produce high-volume computer-based braille embossing. In 1992, the Mountbatten Brailler was introduced as a revolutionary alternative to the mechanical input of the Perkins Brailler, and with the increasing power of desktop computers and piezo-electric cells (tactile braille cells made of materials that respond to electric current by changing their dimensions, developed by Oleg Tretiakov and Franz Tieman), braille-display processors began to permeate the market.

Today, the most expensive part of braille-display processors is the braille cell. In expounding on his own failed attempts to make a cheaper braille cell, Deane Blazie listed the following: displaying braille using an electrical stimulus instead of an actual physical bump, using inverted bubbles like bubble wrap, and using a pneumatic display that used air pressure to push up BBs. Most promising are polymers that can spring up or down when a voltage is placed across them, eliminating the need for electromechanical reeds that must be completely reliable over billions of movements.

Let's Hear It

According to the Helsinki University history of speech synthesis <www.acoustics.hut.fi/~slemmett/dippa/chap2.html>, the first mechanical attempts to synthesize speech took place in 1779, when a Russian professor (Christian Kratzenstein) explained the physiological differences among the basic vowel sounds and produced the sounds artificially by constructing acoustic resonators that were similar to the human vocal tract. Kratzenstein activated the resonators with vibrating reeds that were similar to those in musical instruments. The development of electrical sound-producing devices began in the 1920s and 1930s. Since its earliest days, Bell Labs had been concerned with the properties and analysis of human speech. In 1936, H.W. Dudley developed the voice coder (or "voder"), the world's first electronic speech synthesizer. The voder required an operator with a keyboard and foot pedals to supply "prosody"—the pitch, timing, and intensity of speech that gives it the intonation that makes it understandable (see the web site <www.research.att.com/history/36speech.html>). Just a year earlier, the first Talking Book disc recordings had been made. The technology now existed both to record and to synthesize sound reliably. Many modern electronic synthesizers use the basic design pattern of the voder.