Full Issue: AccessWorld March 2006

Product Ratings

Product Features

Product Features

Feature

ZoomText 9.0

LunarPlus 6.5

Electronic help

Yes

Yes

Installation options

Large print with speech support

Large print with speech support

Magnification levels

Up to 36x

Up to 32x

Speech output

Yes

Yes

Mouse/cursor enhancement

Customization of size, color, and shape

Customization of size, color, and shape

Color/contrast settings

Extensive

Extensive

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Product Features

Product Features

Feature: ZoomText 9.0; LunarPlus 6.5

Electronic help; ZoomText 9.0: Yes; LunarPlus 6.5: Yes.

Installation options; ZoomText 9.0: Large print with speech support; LunarPlus 6.5: Large print with speech support.

Magnification levels; ZoomText 9.0: Up to 36x; LunarPlus 6.5: Up to 32x.

Speech output; ZoomText 9.0: Yes; LunarPlus 6.5: Yes.

Mouse/cursor enhancement; ZoomText 9.0: Customization of size, color, and shape; LunarPlus 6.5: Customization of size, color, and shape.

Color/contrast settings; ZoomText 9.0: Extensive; LunarPlus 6.5: Extensive.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Calendar

March 20-24, 2006

Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference

Orlando, FL

Contact: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education, P.O. Box 3728, Norfolk, VA 23514; phone: 757-623-7588; e-mail: <info@aace.org>; web site: <www.aace.org/conf/site>.

March 20-25, 2006

California State University at Northridge (CSUN) Center on Disabilities' 21st Annual International Conference: Technology and Persons with Disabilities

Los Angeles, CA

Contact: Center on Disabilities, CSUN, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Building 11, Suite 103, Northridge, CA 91330; phone: 818-677-2578; e-mail: <ctrdis@csun.edu>; web site: <www.csun.edu/cod/conf/index.htm>.

April 10-11, 2006

Power Up 2006 Assistive Technology Conference and Expo

Columbia, MO

Contact: Missouri Assistive Technology, Office of Administration of the State of Missouri, 4731 South Cochise, Suite 114, Independence, MO 64055; phone: 816-373-5193; e-mail: <matpmo@swbell.net>; web site: <www.at.mo.gov>.

May 3-5, 2006

2006 Solutions for Assistive Technology Conference

Baton Rouge, LA

Contact: Adaptive Solutions, 2127 Court Street, Port Allen, LA 70767; phone: 225-387-0428; e-mail: <sherry@adaptive-sol.com>; web site: <www.adaptive-sol.com/conference.htm>.

June 8-10, 2006

Collaborative Assistive Technology Conference of the Rockies

Westminster, CO

Contact: Assistive Technology Partners (ATP), 1245 East Colfax Avenue, Suite 200, Denver, CO 80218; phone: 303-315-1280, 303-837-8964 (TTY) or (800) 255-3477; web site: <www.uchsc.edu/atp>.

Letters to the Editor

Singing GoldWave's Praises

I just wanted to say thanks for including the article on how to convert old cassette tapes to digital audio files! ("There's Gold on Those Old Tapes: Recording and Editing Digital Audio Files with GoldWave," January 2006.) I do a lot of singing at church, and a lot of my songs are on tape. However, there are so many advantages to having them on CD, which is why this particular article caught my attention. Since I read it, I've been playing around with Gold Wave and my sound tracks. Awesome program and technology! I love the fact that the hissing noise from cassettes can be removed as well as any humming. I just wish that the pitch effect wouldn't change the quality of the sound if one selects the box that lets the program know that one doesn't want the tempo of a song to change.

Alyssa

January Screen Reader Roundup

I commend you for publishing the update and review of the three screen readers ("The Sound of Computing: A Review of Three Screen Readers") in the January issue. I'd like to comment on the scope of the article, however. The writer only documented experience with Microsoft Word, Excel, and Internet Explorer in general for the three products, noting problems with spell check, missing documentation, etc. Firefox support was also explored. However, no examination of Java support or PDF support was included. PDF support, as we know, is critical for comprehension of some files, and use of Microsoft PowerPoint is critical as well for use of some educational materials. I'd like to see these functionalities covered in a near-term report if possible.

On another note, I note the continued drum beat of cost related to purchase of assistive technology. I agree that AT is expensive, and in some cases not worth the money, but these are choices we make. If purchase of AT makes sense for your use, continuing to keep it current does too.

Finally, just an observation, but I'd love to see an explanation from the RIM corporation of why they choose to ignore the blind population. The Blackberry is the exclusive device for portable e-mail access of government and large corporations, yet RIM does nothing to make their devices accessible. This is a shame for both the government and industry.

Allen Hoffman

The Editor Responds

We cover Word, Excel, and Internet Explorer in our screen reader reviews because they are widely used applications. An extensive amount of work is required to learn to use and test three screen readers in different applications. For more on access to PDF files, read "What's in a PDF? The Challenges of the Popular Portable Document Format" in the November 2005 AccessWorld.

Editor's Page

You may have noticed that starting with this issue, the AccessWorld web pages have been redesigned. We hope you will find them both more appealing and easier to use. Article pages now resemble the AccessWorld home page, and all pages are more colorful and attractive. The navigation links are easier to find at the top of the right-hand column, and the AccessWorld Search is now right on the page, near the top. But if these links get in your way, you can also move them back to the bottom of the page by visiting the "Change Colors and More" page. Screen reader users can select the "Jump to Article" link to go directly to the article on a particular page. And, we have changed AccessWorld's subtitle to "Technology and People Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired." We find that more descriptive, and it will help Internet search engines bring more potential readers to our site. Please e-mail us and let us know what you think of the new design.

To cut down on spam, some web sites and services require new users to type a word that is displayed in a graphic on the screen. The letters are slightly distorted by a background image. This is called visual verification, and it is not accessible for users of screen readers or many people with low vision. Some sites provide an audio pronunciation of the word as an alternative. However, the audio can be hard to understand, too.

Two major players on the web, Google and Yahoo!, use visual verification. They have so far been unwilling to create an accessible alternative. E-mail verification is one current alternative. More work needs to be done to ensure that people who are blind or have low vision are not shut out of online services.

In this issue, Lee Huffman, of AFB's Technology and Employment Center in Huntington, West Virginia (AFB TECH) , reviews ZoomText, version 9.0, from Ai Squared, and LunarPlus, version 6.5, from Dolphin Computer Access, two of the three most popular screen magnification products on the market. MAGic, from Freedom Scientific, will be evaluated in a future issue. Each product was evaluated on its documentation and electronic help, ease of installation, control panel, magnification and display features, and speech output. Its performance was tested in Microsoft Word, Excel, Internet Explorer and Outlook Express. Find out how these programs compared.

Deborah Kendrick interviews Glen Gordon, chief technical officer of Freedom Scientific. Gordon discusses his ongoing work on JAWS for Windows, his career before he joined Henter-Joyce and then Freedom Scientific, and more. Read about a key developer of one of the most popular products in the assistive technology field.

Janet Ingber, author and music therapist, writes about video description of television and movies. The article covers the history of video description, as well as previous attempts to legislate a requirement that networks include description in some programming. Ingber then profiles the players in the description field and explains how they create description and add it to programs.

Darren Burton and Lee Huffman, of AFB TECH, evaluate large stand-alone copy machines. The first in a series of articles to cover different types of copy machines, this one explores the accessibility of units that have been commonly used in offices over the past couple of decades. Future articles will examine the smaller, less expensive desktop units that are now available and review accessibility solutions from Canon and Xerox that have been designed to make their units more accessible and usable for people who are blind or have low vision. Find out how accessible these machines are.

Chris Hofstader, freelance writer and itinerant research scientist, contrasts the audio output of adapted computer games with that of screen readers. He points out that audio games provide access to information through multiple sound cues. In contrast, screen readers generally do not include sounds as additional information. Instead, they provide a single stream of speech output. Video game developers have led the way to many of the most interesting discoveries in mainstream computing. Perhaps audio games can perform a similar service.

I report on the seventh annual conference of the Assistive Technology Industry Association (ATIA), held on January 18-21, 2006, in Orlando, Florida. The ATIA conference featured many new products and product updates, as well as a number of sessions of interest to people who are blind or have low vision. Learn what we found in the exhibit hall and conference sessions.

Jay Leventhal

Editor in Chief

Product Ratings

Ratings Chart

Feature: ZoomText 9.0; LunarPlus 6.5

Documentation; ZoomText 9.0: 4.0; LunarPlus 6.5: 3.0.

Ease of installation; ZoomText 9.0: 4.5; LunarPlus 6.5: 4.0.

Navigating the control panel; ZoomText 9.0: 4.5; LunarPlus 6.5: 3.5.

Color and contrast settings; ZoomText 9.0: 4.5; LunarPlus 6.5: 4.5.

Speech output; ZoomText 9.0: 4.5; LunarPlus 6.5: 3.0.

Magnification features; ZoomText 9.0: 4.5; LunarPlus 6.5: 4.0.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.

Focus on Screen Magnification, Part 1: A Review of ZoomText 9.0 and LunarPlus 6.5

This is the first of two articles on the three leading screen magnifiers. In this article, I evaluate ZoomText, version 9.0, from Ai Squared, and LunarPlus, version 6.5, from Dolphin Computer Access. A future article will evaluate MAGic, from Freedom Scientific.

For this evaluation, I compiled a list of features that are commonly associated with screen magnifiers and integrated screen magnifier/screen readers, including documentation and electronic help, ease of installation, control panel, magnification and display features, and speech output. For each feature, I evaluated the programs' performance in Microsoft Word, Excel, Internet Explorer, and Outlook Express on a Pentium 3, 1133MHz, computer with 256MB of RAM, running Windows XP Professional.

ZoomText, Version 9.0

The version of ZoomText 9.0 by Ai Squared available at the time of this writing and the one evaluated is actually version 9.01.1, the third of several updates to fix a number of problems. ZoomText 9.0 itself comes in two versions—Magnifier, a stand-alone screen magnifier, and Magnifier/Screen Reader, an integrated screen magnifier and screen reader. Both versions have minimum requirements of a 450 MHZ Pentium 3 processor or equivalent and one of the following operating systems: Microsoft Windows 98, NT 4.0 (SP 6), 2000, ME, or XP. Internet Explorer 5.0 or later, a minimum of 256 RAM (512 recommended), and a minimum of 25 MB of hard disk space are required to run the program (an additional 60 MB is required for each new, human-sounding NeoSpeech synthesizer). A sound card is also required for the Magnifier/Screen Reader.

Documentation and Electronic Help

ZoomText is shipped with a User's Guide in 16-point font, a Quick Reference Guide in 14-point font, and the installation CD. Although the documentation is informative and well organized, its presentation could be improved by increasing the font size in both manuals to the American Printing House for the Blind's recommended 18-point font and increasing the size of the graphics. On several pages, the manuals show examples of on-screen menus and dialog boxes that have tiny print and are not visible to people with low vision. Another modification that would make the manuals easier to use would be to change their paperback bindings to spiral bindings, which would keep the pages flat for ease of reading by those who use handheld magnifiers or closed-circuit televisions (CCTVs) and would fit much better on a CCTV's x-y table.

As with most screen-enhancement programs, you can use hot keys to access ZoomText features quickly. Currently, you must look up forgotten hot keys in the User's Guide or the electronic User's Guide from the Help menu on the Control Panel. It would be helpful to have these hot keys listed separately on large-print quick-reference sheets that you could keep next to your PC, similar to the ones that come with LunarPlus.

From the Help menu on ZoomText's main Control Panel, you can access the program's electronic User's Guide and the Help Tool, which describes the toolbar buttons and their functions in a dialog box that is supported by speech. You can also access online help from the Ai Squared web site, check for program updates, download program components, transfer your product license, register your product, receive e-mail technical support, read release notes, and read your ZoomText product information. As you can tell, the Help button on the main Control Panel offers a wealth of help.

Ease of Installation

Installing ZoomText is quick and painless. When the ZoomText program CD is inserted into the disk drive, the installation starts automatically. The installation prompts are all in large print and are accompanied by speech. After installation is finished, you have the option to activate the program immediately or anytime within the next 30 days. Until the program is activated, it will run as a trial version with all the functionality of an activated program. After 30 days, the software must be activated for you to continue to use it.

ZoomText can also be purchased and downloaded immediately from the Ai Squared web site. Ai Squared then follows up the online purchase and download by shipping print manuals and an installation CD to the buyer.

The Control Panel

When you start ZoomText, the Control Panel appears on the screen and contains all the controls for using the program. The Control Panel is well organized. It gives you the ability to switch between the Magnifier and Screen Reader toolbars with the click of a mouse button. The Screen Reader Toolbar gives you access to the program features that are associated with screen reading and speech output, such as AppReader, speech rate, and the echo settings. The Magnifier Toolbar allows you to access screen display features, such as the magnification level, viewing options, and color and contrast settings.

The Toolbar buttons are grouped by function and are labeled with a clickable link that opens the group's associated dialog box. Each Toolbar button is also labeled with a colorful icon and large-print label, and by default, each becomes highlighted when touched by the mouse pointer, which makes the buttons easy to identify. Most buttons also have pull-down menus that give access to frequently used settings and features.

Magnification and Display

New to this version of ZoomText are additional magnification levels. For those who think that 2x is not large enough and 3x is too big, 2.5x has been added. In addition, 18x, 20x, 24x, 28x, 32x, and 36x have been added to the levels of magnification. Greater than 16x may be overkill, however, because once the letters get that big, you lose your orientation on the screen.

X-font is another addition to the new ZoomText version. This technology keeps various sizes and types of fonts in clear focus at all magnification levels and in different applications, including the tested applications of Microsoft Word, Excel, and Outlook Express. This is a feature that screen-magnification users will surely appreciate. We are used to the frustration of degraded text clarity in the magnified view, especially with small, italic, and cursive fonts. X-font fixes this problem to a large degree, but do not expect all text to be completely smooth. There is still a small amount of degraded text, especially on web sites as tested through Internet Explorer. According to Ai Squared, X-font technology does not apply to images—that is, to text that appears in company logos, pictures, application toolbar icons, stylized clickable buttons, or advertisements on a web page.

Through the Magnification toolbar, you can also customize the screen display in all four tested applications by adjusting the colors, pointer, and cursor. For each, you can choose from preset schemes or use the customize tool to fine-tune the display to meet your preferences.

ZoomText gives you eight Zoom Windows (the style of the magnified view) from which to choose: Full, Overlay, Lens, Line, and four Docked positions. Each offers a unique way of viewing material on the screen.

The Freeze Window is another feature offered by ZoomText. It allows you to hold one portion of the screen stationary while you simultaneously move and work in another area of the screen.

Still another new feature is Text Finder. This feature is accessed through the Magnifier toolbar and is much like the Desktop Finder and Web Finder tools that you may be familiar with from ZoomText 8.1. Text Finder helps you to locate a word or a phrase within an active application window or the entire screen. Once the word or phrase is found, ZoomText highlights and reads each occurrence. This is a helpful feature that will save you time and scrolling when you are looking for a specific place in a long document or another application.

Application Settings is yet another new feature of ZoomText. Now, within each ZoomText configuration, you can select and save unique settings for each application. For example, you can set your spreadsheet program at one magnification level, your web browser at another, and your word-processing program at still another. When you move between applications, each unique application setting is automatically restored.

The Zoom Window, Freeze Window, Text Finder, and Application Settings features all work well with Microsoft Word, Excel, Outlook Express, and Internet Explorer.

Speech Output

ZoomText provides speech output for most functions that are accessed through the mouse or keyboard, including reading documents, web pages, e-mail, window titles, menu bars, and menu lists. Verbosity can be set to different levels and customized to your preferences. ZoomText offers two options for reading full text documents, web pages, and e-mail—AppReader and DocReader. These two reading features are useful for text, but they are not intended for or well suited to Microsoft Excel because of its row and column style of layout.

AppReader reads text within the parent application, and your view of the document does not change, which gives you the ability to transition between reading and editing. As each word is read, it becomes highlighted, and the highlighting can be customized to your preferences.

DocReader reads text in a special environment window where text is reformatted and customized for easier viewing. Text can be presented in a single line (Ticker) and as wrapped lines (Prompter), with your choice of fonts, colors, word highlighting, and magnification level. However, the DocReader toolbar cannot be magnified, which makes it inaccessible to many people with low vision. In addition, the up and down arrows on the speech rate and magnification level spin boxes are small and hence will not be visible to many with low vision. It may not matter that much, though, because the up and down arrows on the speech rate spin box do not work anyway. The number in the spin box changes, but the speech rate does not. Even the hot keys to increase and decrease the speech rate do not work on the fly in DocReader; this is a bug that Ai Squared needs to squash!

Another new feature of ZoomText is the Reading Zone. This feature allows you to see and hear selected areas in an application window. For example, if your database shows several fields and you are only interested in seeing three of them, you can see the selected fields with the press of a hot key. You can set up to 10 reading zones per application and move among them as needed. This is an advanced feature and takes some practice to use effectively.

The Speak It tool reads selected areas of the screen by clicking on them or dragging the mouse. The text on the screen is spoken even if it is not in the active application. The Speak It tool reads words, numbers, menu items, and even icons in a toolbar. It does not, however, read text in graphical images, such as those that are associated with graphics and advertisements on web pages retrieved in Internet Explorer.

Many will find the best new ZoomText feature to be the human-sounding NeoSpeech Synthesizer. With NeoSpeech, you can choose to have either Paul (the male voice) or Kate (the female voice) read the on-screen text. The NeoSpeech volume and speech rate can also be adjusted to your preference. The speech rate is adjusted in terms of a percentage, instead of in words per minute, with 50% speed being the default setting. The new synthesizer options will make using the program more pleasurable for many users because the speech is much less robotic sounding. However, power users may not care for it as much. Although NeoSpeech is much more human sounding, there is a noticeable lag between sentences at higher speech rates, which may annoy people who prefer high-speed speech. For them, and anyone else, for that matter, ZoomText comes with three additional speech synthesizers: TruVoice, ViaVoice, and Microsoft Speech. It also supports other SAPI 4 and 5 synthesizers that may already be installed on your computer.

The Bottom Line

The new ZoomText Magnifier/Screen Reader is much better than its previous version. Its ability to customize aspects of the display and speech output is excellent, and thus it can meet the needs of most computer users with low vision. Furthermore, ZoomText has many new features that increase the usability of the program. As previously mentioned, the documentation could be improved, as could the ability to resize the DocReader toolbar and to adjust the speech rate on the fly when using DocReader. The NeoSpeech synthesizer could also be improved by making the speech clearer and decreasing the lag between sentences in the high-speed settings.

LunarPlus 6.5

LunarPlus 6.5 is the latest magnifier/screen reader program offered by Dolphin Computer Access. It combines Dolphin's screen magnifier, Lunar, with basic speech output and is compatible with the following operating systems: Windows 98, 98 SE, ME, NT 4.0 (SP 6), 2000, and XP with Internet Explorer 5.5, and MSAA installed. The minimum requirements also include an Intel P2 processor with 400 MHZ or equivalent, 128 MB of memory, a video card with 4 MB of memory, a Sound Blaster compatible sound card, and 125 MB of free hard disk space.

Documentation and Electronic Help

In addition to the installation CD, LunarPlus ships with a User Manual in DAISY format and an IBM ViaVoice synthesizer CD. Also in the package are a LunarPlus User Manual, a Getting Started Tutorial for Dolphin Software Manual, and an Introducing Windows Manual, all in 16-point font, as well as three laminated, double-sided Quick Reference Sheets for Hot Keys that have diagrams and various size fonts.

The spiral bindings on the manuals make them easy to handle while reading, and the manuals fit well on a CCTV's x-y table. The User Manual is somewhat confusing, though, because of its layout and description of information. For example, the first sentence in the Installation chapter of the LunarPlus User Manual reads, "The installation of LunarPlus is easy!" and then takes the next 19 pages to explain it. Too much detailed information is presented on situations that most people will neither encounter nor understand, and it may overwhelm or confuse people who are new to screen-magnification software or are not computer savvy.

That the Getting Started with Dolphin Products Manual is not specific to LunarPlus may increase the likelihood of misunderstanding, since the reader must sort out which sections pertain to LunarPlus and which do not. The Quick Reference Sheets that list information on hot keys are also not specific to LunarPlus, but contain information on other Dolphin screen-enhancement and screen reader programs as well. While the Quick Reference sheets are a great feature, they could be improved by removing all references to other Dolphin programs. All documentation that comes with a product should be product specific.

The Introducing Windows manual gives easy-to-understand, basic computer information and definitions that will be helpful to those who are new to using Windows, but this information may be unnecessary for people with computer experience.

All three manuals that are shipped with the program and the LunarPlus Version information are also accessible through the Help button on the LunarPlus control panel. Another useful feature is that both general and context-specific help are available by clicking on the Help button or question mark associated with the dialog box. It would be helpful, however, if there was also a link to the Dolphin home page from the Help menu on the Control Panel.

Ease of Installation

The LunarPlus program installation automatically begins when the CD is inserted into your computer and is fairly simple to perform. The installation prompts are all in large print and are supported with speech. During this installation, you must install three components: LunarPlus, Microsoft Active Accessibility (MSAA), and Synthesizer Access Manager (SAM). LunarPlus provides the access tools and interface that bring screen magnification and speech output. MSAA—a set of programming language enhancements and standards—allows applications to make useful information available to screen readers and other accessibility aids. SAM provides for the sharing of speech synthesizers and braille displays between compliant access aids.

LunarPlus cannot be downloaded and purchased from the Dolphin web site; you must contact the company directly or purchase the program from a dealer. A free, 30-minute demonstration version, however, can be downloaded from the web site. From a practical standpoint, 30 minutes is not nearly enough time to try out a screen-enhancement product. This time frame should be extended to a 30-day trial period.

You cannot have more than one version of LunarPlus installed on your computer at one time. If you have a previous version already installed and you want to upgrade to the new version, you should follow the instructions as if you were installing LunarPlus for the first time, so as to install the newest version directly over your old one. When you do so, most of your preferred settings will automatically be imported into the new version, which makes upgrading your program much easier.

Another option is available when you purchase LunarPlus: You can purchase the LunarPlus Pen edition of the software. Unlike most other screen-magnification software, the LunarPlus Pen is not installed on the PC. Instead, it runs from a USB Pen Drive, a small device, approximately 7 centimeters by 2 centimeters, that plugs directly into a spare USB port of a computer.

With the LunarPlus Pen, your LunarPlus program is truly portable. You can carry the LunarPlus software with you and run it on any Dolphin Pen-friendly computer. To make a computer Dolphin Pen friendly, you download the Dolphin Interceptor from the Dolphin web site. Downloading the Dolphin Interceptor may require sighted assistance and Administrator rights, but after you do so, the next time you insert the LunarPlus Pen, the screen-magnification software will run automatically.

The Control Panel

The LunarPlus Control Panel appears on the screen when the program starts, and it contains all the configuration settings for LunarPlus within a menu system. The most commonly used settings can be accessed through the two property sheets in the main Control Panel: the Visual property sheet and the Speech property sheet.

The Visual property sheet gives access to program features that are associated with screen display, such as magnification level, display modes, and color changing. The Speech property sheet gives access to program features that are associated with speech output, including speech rate, character echo settings, and user-defined voices. These two property sheets have the same general layout. The main section gives direct access to the most basic settings for the speech or visual features, and the right side has a group of buttons that give access to additional settings. These buttons represent categories of settings with related functionality. Each button opens a dialog box, allowing you to make desired changes. The menu bar across the top of the property sheets contains all the settings that can be found on the property sheets, as well as some more-advanced settings.

Although functional, the Control Panel could be made more user friendly. It would be useful if more settings were available directly on the property sheet without having to navigate to other tiers. It would also be helpful if there was a greater use of color coding and representational icons on the property sheets, such as the ones used on the Mode section of the Visual property sheet.

Magnification and Display

LunarPlus offers magnification up to 32 times, which may sound like a good thing, but, in practice, magnification over 16x is not practical. On the other hand, LunarPlus offers many fractional levels of magnification under 4x, which is helpful.

One problem is that the magnification cannot be changed while using the Document Read feature. The reading must be stopped, the magnification level adjusted, and the Document Read feature restarted. This is a cumbersome process and interferes with the efficient flow of work. In addition, in the Enhanced Document Read feature, the magnification level of the magnified line at the top of the screen cannot be changed. The ability to adjust this level of magnification would improve the usability of this feature.

From the Visual property sheet, you can adjust the screen's colors. You can select a preset color scheme, replace problem colors, and further refine the color setting through custom settings. You can also customize the style and color of the cursor and mouse pointer to meet your viewing preferences.

LunarPlus offers eight different screen magnification styles: Full Screen; Fixed Window; Lens; Auto Lens; and Right, Left, Top, and Bottom Split Screen. The position and size of these windows can also be adjusted to suit your needs.

Line View is another way of viewing text with LunarPlus, in which lines of text are reformatted into one continuously scrolling line, which works much like a marquee moving across the center of the screen. Unfortunately, this feature does not provide speech support.

The Application Settings feature is also offered on LunarPlus. As with ZoomText, Application Settings allows you to create and save unique settings, such as magnification level and color changes, for each application that you use. These settings are automatically restored when you change applications.

Speech Output

LunarPlus uses its Dolphin Orpheus synthesizer, which is compatible with Via Voice, SAPI, and other synthesizers that you may have already installed on your system. LunarPlus provides speech output for most functions that are accessed through the mouse or keyboard, including reading documents, web pages, e-mail messages, window titles, menu bars, and menu lists. Verbosity can be set to different levels and customized to your preferences. The status of a check box or radio button in a dialogue box, however, is not spoken, nor is the information in a message box.

In Microsoft Word, LunarPlus does a good job of reading by word, line, or the entire document. In Excel, it reads row and column headings, as well as the contents of the cell. When it comes to speech support for Microsoft Internet Explorer and Outlook, however, there is room for improvement. In Internet Explorer, LunarPlus does not read a link when the mouse pointer is positioned over it, unless the link is actually selected. In addition, it begins reading a web page at the top, and if you want to stop in the middle and then restart, you have to start from the top again. Apparently, there is no way to start reading from a desired point in the text of a web page. The same seems to be true for e-mail messages in Microsoft Outlook. This is a significant problem that leads to frustration and wasted time. The ability to start and stop at any point on a web page or e-mail message is essential, especially when you are working with lengthy texts.

The Bottom Line

LunarPlus is a robust screen-magnification program that incorporates basic speech output. The program gives you the ability to customize the screen display to meet your preferences and will work well for many people with low vision.

Streamlining, simplifying, and making the documentation more specific to LunarPlus would further improve the overall product. The ability to adjust magnification on the fly while using the Document Read feature would be an improvement, as would be the ability to adjust the size of the magnified line at the top of the screen in the Enhanced Document Read feature.

The greatest need for improvement is in speech output. The addition of a more human-sounding voice would make the program more pleasant to use. In addition, expanding speech support to include check boxes, radio buttons, and message boxes would increase the functionality of the program, and enhanced speech support for Internet Explorer and Outlook would make LunarPlus more user friendly.

All Things Considered

After careful review of both these screen magnification programs, it appears that ZoomText would better meet the needs of most computer users with low vision. There are four main reasons: ZoomText has (1) superior speech support for all applications, (2) many more available features, (3) a more user-friendly designed Control Panel, and (4) a better-organized and easy-to-understand set of documentation. Dolphin Computer Access makes the point that LunarPlus is not a screen reader, but a screen magnifier that provides basic speech output, but at the same price as ZoomText, I expected more from it. ZoomText offers you more for your money.

Before you make your own decision, you can become a more informed consumer by visiting the web sites of both manufacturers to learn as much as you can about each product. You can also download free trials of the products and try them out, so you can choose the screen magnifier/screen reader that is right for you.

Manufacturers' Comments

Ai Squared

"First, our new xFont technology reliably smoothes all font-based text in web pages. Only text appearing in graphical images is not smoothed. Second, although the SpeakIt tool does not read graphics in web pages (no screen reader can do that), it will read the Alt tag text for images, when it exists. And finally, we have reproduced the problem with the speech rate buttons in DocReader, and will resolve this problem as quickly as possible."

Dolphin Computer Access

"Dolphin always welcomes feedback from the marketplace. We are currently reviewing all of our documentation for all products and do appreciate that in some cases the level of information supplied is too extensive. We have tried to ensure that all the necessary information is supplied as part of the product as a complete package; however, with all of the documentation available from within the online help, it is certainly worth reducing the level of hard-copy documentation. Simplified documentation is certainly a priority for us and will be addressed in future product releases. It is worth reiterating that Dolphin's LunarPlus enhanced screen magnifier provides outstanding screen magnification coupled with entry-level speech (as a backup for low vision users, rather than full screen-reading capabilities). Dolphin's Supernova reader-magnifier, however, provides the same unparalleled screen magnification access coupled with fully customizable screen reader speech output and braille support. Supernova gives the user many of the speech features requested by the reviewer, such as the ability to start, stop, and restart the reading of e-mails and web pages, or start and restart the reading of web pages and e-mails at a user-selected point."

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Product Information

Product: ZoomText 9.0.

Manufacturer: Ai Squared, PO Box 669, Manchester Center, VT 05255; phone: 802-362-3612; web site: <www.AiSquared.com>.

Price: ZoomText 9.0 Magnifier, $395; ZoomText 9.0 Magnifier/Screen Reader, $595.

Product: LunarPlus 6.5.

Manufacturer: Dolphin Computer Access, 60 East Third Avenue, Suite 130, San Mateo, CA 94401; phone: 866-797-5921; web site: <www.dolphinusa.com>.

Price: Lunar (no speech), $395; LunarPlus (with speech), $595; LunarPlus Pen edition, $690.

AccessWorld News

Optelec Expands Product Line and Staff

Optelec has announced the addition of Jaap Breider to its executive management team, as technology officer for blindness products. Twenty years ago, Breider, who is blind, founded ALVA, the Netherlands-based supplier of refreshable braille terminals.

"Both Optelec and ALVA have historically been two leading providers of access technology from one small country," Breider announced. "I am excited to be working with such a committed team of professionals, and look forward to meeting many of you at various conferences and events in the not-too-distant future."

In September 2005, Optelec acquired the assets of the erstwhile ALVA, so Breider's addition to the management was a less-than-surprising step. Meanwhile, Optelec U.S. has announced a strategic alliance with VisionCue, an Oregon-based technology supplier. Larry Lake, president of VisionCue, was formerly with ALVA Access, so he brings considerable familiarity and expertise with the ALVA line. For more information, visit: <www.optelec.com>.

OPAL Added to the TOPAZ Line for Seeing on the Go

At the annual conference of the Assistive Technology Industry Association (ATIA) in January 2006, Freedom Scientific unveiled its new "ultra-portable video magnifier," called the OPAL. The OPAL contains a small camera and displays images on a brightly lit 4-inch screen. The magnification level can be varied from 3x to 6.4x with a sliding fingertip control while the unit rests firmly on a document.

A recent press release from the company stated that "the OPAL features simple, ergonomic controls. Simply turn it on with a push of a button, place it on an object or document, and use the zoom slider to adjust the magnification for the best reading comfort. A single button can switch between seven different viewing modes—indoor and outdoor full-color modes and five contrast modes for reading text."

The unit is small enough to be carried in a pocket or purse and can be used for all small reading needs on the go. It can be attached to a television screen or computer monitor for additional enlargement when at home or in the office. The product will be available in March. For more information, contact Freedom Scientific: phone: 800-444-4443; web site: <www.freedomscientific.com>.

Bluetooth Braille Keyboard Accompanies the Maestro

HumanWare Canada has announced the availability of a portable Bluetooth braille-style keyboard to accompany its Maestro PDA. The Maestro is an adapted off-the-shelf handheld device that incorporates the Trekker GPS system with such features as a calendar, notetaker, DAISY book reader, voice memo recorder, and contacts manager.

Although the Maestro has a tactile overlay keyboard that enables you to enter text in a braille format by pressing one "dot" key at a time, the new wireless keyboard offers another alternative: Braille can be entered in either computer braille or contracted braille formats. In its small carrying case, the keyboard offers what will be for some a faster, more efficient method of entering text into the Maestro. For more information, contact HumanWare: web site: <www.humanware.com>.

Cicero Upgrade Released in Britain

Dolphin Computer Access has announced the release of Cicero, version 3.0, an upgrade that the company says enhances the user's ability to manipulate hard copy and electronic text. An optical character recognition program, Cicero translates letters, magazines, books, and the like and offers the user with low vision a variety of options to magnify text, change color schemes, manipulate format, and more. Cicero 3.0 uses the Abbyyy Finereader recognition engine, noted for its OCR accuracy. It is available in British English, U.S. English, and 36 other languages. For more information, contact Dolphin Computer Access: phone: 0845-130-5353; web site: <www.dolphinuk.co.uk>.

Easier Surfing

EITAC Solutions Group has developed the MaximEyes toolbar to make surfing the web easier for people with low vision. The MaximEyes toolbar is a plug-in for Internet Explorer 6.0, which provides a combination of features that will help reduce eye strain. Features include the ability to magnify the entire web page from 1x to 16x; to speak text aloud using the Click-and-Speak tool; and to customize background, text and link colors for better contrast. In addition, the MaximEyes toolbar has a giant mouse pointer, toolbar buttons, and dialogs. To download a free 14-day trial version, visit: <www.bigtoolbar.com>.

ATIA 2006

The seventh annual conference of the Assistive Technology Industry Association (ATIA) was held on January 18-21, 2006, at the Caribe Royale hotel in Orlando, Florida. More than 1,500 people attended, and more than 120 exhibitors showed products for people with a range of disabilities.

This conference offered better access for people who are blind than did previous conferences. The hotel staff were well trained and helpful, and braille menus were available in hotel restaurants. Red carpeting was again used to assist people in navigating among the hotel towers and the convention center where the events were held.

However, as did previous conferences, this one had some access problems. The people who worked at the conference registration were not trained in how to communicate with people who are blind. They also did not know what was on the CDs that were handed out with the registration packets. In addition, the covers of the volumes of the braille conference program contained only raised print. This format was convenient for sighted people, but meant that braille readers had to open the volumes to find out what each one contained. It would have been much better to have both braille and print on the covers.

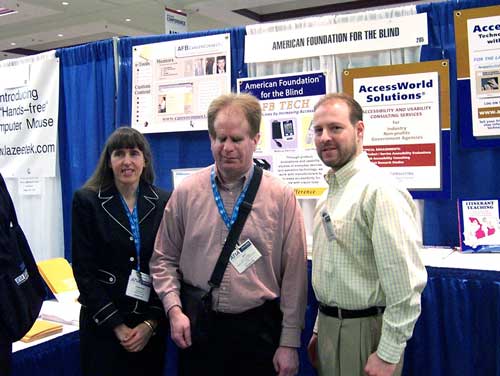

Caption: The American Foundation for the Blind booth at ATIA. From left: Crista Earl, Jay Leventhal, Lee Huffman.

Conference Sessions of Interest

ATIA featured sessions that appealed to people of various levels of expertise, including sessions introducing new products and updates to products, sessions on different ways to use products in the classroom and elsewhere, and sessions reporting the results of research studies. There were a number of sessions on the National Instructional Materials Accessibility Standard (NIMAS), which guides the production and electronic distribution of digital versions of textbooks and other instructional materials so they can be more easily converted into accessible formats. These presentations were made by representatives of publishers and educational agencies, teachers, and assistive technology developers. The aim is to get accessible textbooks into the hands of students in a timely manner.

Numerous manufacturers demonstrated the latest updates to their products. For example, Cathy Gettel, of Ai Squared, demonstrated the new features of ZoomText 9.0; how to access the Internet, e-mail and other applications; and how users can increase their speed and accuracy in computing tasks.

Nancilu McClellan, of Metroplex Voice Computing, demonstrated MathTalk, which allows users to dictate math problems into a computer with speech feedback. The user can then speak a command that will save the file, open Duxbury, open the file in Duxbury, and translate it into braille. It does best with linear math but does not do column math well. As it is developed further, it should prove to be a useful tool for users who want to create print and braille math problems or worksheets.

Jonathan Lazar, of Towson University, presented research on the problems that users of screen readers experience. In his study, 100 users of screen readers browsed the web for two hours and reported on the problems they encountered. The most common problems that they noted were (1) confusing feedback from the screen reader caused by the page layout (36); (2) no or misleading alt text for pictures (33); (3) conflict between the screen reader and the application (28); (4) poorly labeled or unlabeled forms (23); and (5) screen reader crashes, inaccessible PDF files, and misleading labels for links (each had 15).

The findings were compared with those for 200 sighted people who took the same test. The results showed that the screen-reader users were much less likely to reboot the computer or restart the program and were much more likely to find alternative solutions than were the sighted users. The conclusion was that blind users waste less time and are more effective in responding to the problems they encounter with computers.

New Products

Freedom Scientific introduced a new line of CCTVs called TOPAZ. The TOPAZ magnifies from 2x to 70x on a 19-inch monitor. There are five models: 17-inch and 19-inch LCD (liquid crystal display) models with slim, nonglare screens; 15-inch and 17-inch CRT monitor models; and a camera-only model. The viewing modes include full color, black on white, enhanced black on white, inverted white on black, yellow text on blue, and blue text on yellow. The prices range from $1,995 to $2,995.

Optelec launched the EasyLink 12, a wireless braille keyboard with a 12-cell refreshable braille display that is designed to give persons who are blind wireless access to their PCs, PDAs (personal digital assistants), and smart phones. EasyLink 12 is compatible with desktop and pocket screen readers. It measures 5.9 inches long by 3.8 inches wide by 0.8 inches thick.

Pocket Hal, from Dolphin Computer Access, and Mobile Speak Pocket, from Code Factory of Spain, are two new screen readers for pocket PCs. Both products can run on a variety of off-the-shelf pocket PCs and provide access to numerous applications.

Bookshare.org now offers its members New York Times top-10 best-sellers in fiction and nonfiction (both hardcover and paperback.) The Bookshare collection now includes over 26,000 books.

HumanWare released version 7.0 of the KeySoft software for its BrailleNote family of PDAs. KeyBase is a new database manager that permits the easy creation of your own databases. KeyBase ships with many useful databases already created. Other new additions include interactive fiction games, braille input for JAWS for Windows, Bluetooth synthesizer and braille display connections with your computer, and Eloquence speech and FM radio for the BrailleNote and VoiceNote mPower.

This is just a sampling of the knowledge and networking opportunities that were shared by the participants at the conference. The ATIA conference continues to grow and has become an important yearly event in the field of assistive technology.

What Screen Readers Can Learn from Audio Games

I find myself alone inside the highly fortified research center with the knowledge that I must find my way into the innermost sanctum and stop the evil scientist from completing the experiment that went wrong. Along my way through the complex maze, I encounter mutants that try to kill me, crazed scientists who try to steal my gear, tools and weapons that can help me in my quest, and all sorts of other surprises that are thrown in my path. To make matters more difficult, I must perform all my actions—from shooting at monsters to navigating the rooms and hallways—entirely blind.

Shades of Doom

This is the scenario one finds oneself in when playing Shades of Doom from GMA Games, a leader in the development of complex virtual environments for audio game players. In 1998, David Greenwood, founder of GMA Games, started exploring the possibility of creating a three-dimensional (3-D) auditory environment in developing this exciting new world of audio interfaces for games.

According to Justin Daubenmire, president of BSC Games (the gaming division of Blindsoftware.com), a major breakthrough in the audio gaming industry was the release of a prototype version of Shades of Doom in November 1999, almost a year after Greenwood began gathering ideas about designing a revolutionary real-time, audio-interface game. "The game stood out from previous audio games because of its emphasis on action. Older audio games tended to be organized around text menus, with small puzzles or arcade games woven into the game play. While these are still popular, Shades of Doom is a 3-D world that allows the audio gamer to explore an interactive realm. It made the audio-game industry much more ambitious."

Shades of Doom was released to the public on May 31, 2001, and immediately changed the landscape of audio games by delivering a real-time action audio game featuring a first-person shooter, joystick support, a cheat code, nine levels, original music, lots of weapons and monsters, realistic sounds, braille printer-ready maps, and easy-to-use keyboard commands.

Those of us who work or have worked in the assistive technology field tend to believe that our products (such as JAWS, ZoomText, and Kurzweil 1000) demonstrate the greatest level of innovation and solve the hardest user-interface problems that a person who is blind or has low vision may encounter. Sorry, everybody, but the game hackers have us beat hands down. Developers of assistive technology should not feel too bad, though—video game developers have led the way to many of the most interesting discoveries in mainstream computing, including high-speed graphics adapters, multichannel audio devices, and inexpensive haptics or force-feedback products.

The description of Shades of Doom, provided by GMA, explains that you will hear up to 32 distinct sounds simultaneously. You need to navigate by listening to the direction of the wind and by the sounds of footsteps and breath echoing off walls. Meanwhile, you need to listen for monsters, treasures, crazed scientists, and lots of other goodies that you may encounter.

Less Speech Saves Time

Although a 3-D audio game like those from GMA can deliver up to 32 sounds at once, a screen reader or other speech product can deliver only a single syllable at a time. When I first went to work at Henter-Joyce, in 1997, Ted Henter would frequently remind us to use as few syllables as possible to deliver information to the user. Thus, JAWS says "star" instead of the more descriptive "asterisk" when it encounters that character. When you hear "star," you know what JAWS means and need to wait for only a single syllable, rather than the three syllables in the word asterisk.

If you consider that a syllable that is spoken by a speech product is equal to a unit of time (the amount of time will vary, depending on the synthesizer's speech rate), fewer syllables spoken means less time spent reading the text. Any person who is blind or has low vision who needs to collaborate with sighted colleagues on a large document will undoubtedly notice how much longer it takes to perform tasks like finding and integrating changes with a screen reader than with vision and a mouse.

With each new release, JAWS and Window-Eyes increase the amount of text that is generated by the screen reader to augment the information on the visible screen. Using Internet Explorer as an example, you hear the word link before you hear the name of the link, you hear combo box when you land on one, you hear edit when you land in a text-entry field, and so forth. In all these cases, the screen reader has added one to three syllables to the information that you are actually interested in hearing, and, as a result, up to three units of time have been added to your web-browsing session. If you are reading a Yahoo! or Google page with hundreds of links and controls, your session grows by the time it takes to deliver all the extra syllables.

Will Pearson, an expert in computer interfaces for people who are blind at the University of Bristol in England, suggested that "Through the use of multiple sounds, audio games have found the ability to deliver a lot of information to a player in an efficient and understandable manner. In terms of implementing this in a screen reader, the challenge is to work out how the human brain processes these multiple sounds to give us a better understanding of how the brain deals with multiple streams of information. Once we know this, it should be possible to create screen readers that offer significantly higher efficiency for a user than today's screen-reader offerings, in addition to access to activities that are currently considered inaccessible."

In Home Page Reader (HPR) from IBM, a user can replace some words with a sound that plays at the same time that HPR is speaking something, a big help in improving efficiency. The Freedom Scientific software team took the concept of decreasing the number of syllables to improve efficiency a step further with the introduction of its Speech and Sounds Manager in JAWS 5.xx. This utility lets a user replace a wide array of different things that JAWS would otherwise say with a sound that can play simultaneously to the text being spoken. For instance, I have JAWS set to play a little "ding" when I encounter a link on the Internet. So, when I read a newspaper, I hear the ding at the same time as I hear "News," "Weather," and so on. Thus, I save one unit of time for each link that I encounter. Unlike HPR, though, the JAWS Speech and Sounds facility is available in all applications, not just on the Internet.

Why should manufacturers of screen readers care? The less time that people who are blind or have low vision spend reading their e-mail, web page, word-processing document, or spreadsheet, the more time they can devote to their jobs, studies, and other tasks on a computer. Thus, they can gain some ground in the constant battle to become more competitive with their sighted counterparts. Ostensibly, a screen reader that can reduce the amount of effort that is required to complete tasks, limit fatigue, and provide people who are blind or have low vision with a more efficient tool will win out in this highly competitive market.

According to Pearson, some preliminary research results demonstrate that when listening to a speech synthesizer read text, people who are blind use more of their brains than do sighted people reading the same text visually. Although this is very preliminary data, it raised some questions: Do blind people suffer greater fatigue from hearing their text read by a synthesizer than sighted people do when reading text visually? Is there a theoretical maximum number of syllables that an individual can hear and comprehend in a single session, and will this number represent less information than a sighted person can read and understand in the same amount of time?

Today, two companies are working to push audio interfaces forward. Coincidentally, they both develop products for delivering mathematical information to users. Henter Math, founded by Ted Henter, developed and sells Virtual Pencil, and ViewPlus, a company founded by Oregon State Professor John Gardner, offers the Accessible Graphing Calculator (AGC). Both Gardner and Henter push the innovation envelope for delivering information in an audio format. Both products offer a major step forward by providing access to previously inaccessible information. Henter can now, for the first time in his life as a father, help his daughter do her arithmetic homework, and many children who are blind or have low vision can now use Virtual Pencil to perform basic arithmetic and algebra in the same manner as their sighted classmates. When I need to do math that involves a graph, I use AGC, as do many students and professionals who are visually impaired around the world.

If the technology that is available today can power the complex environment of Shades of Doom and other similar games, how can the people who make speech products for users who are blind or have low vision exploit the same elements of the operating system to provide a profoundly more efficient system for routine tasks? I commend Freedom Scientific for entering uncharted areas with its Speech and Sounds Manager, but, in most cases, Speech and Sounds Manager can be used to deliver only 2 pieces of information simultaneously, while the gamers can deliver 32.

Clearly, the gamers have an edge because they know the narrative of the adventure and can predict with certainty the finite number of actions that a player may make at any given moment. Conversely, it is impossible for a screen reader to know what a user will type next, what part of a word-processing document the user will find interesting, or the value in a random cell in a spreadsheet. This does not, however, prohibit screen readers from becoming more efficient by moving from a one-dimensional interface to one more like those found in the games.

The audio game developers seem isolated not only from the assistive technology companies, but from the research community. While there have been a number of studies on the efficiency of screen readers, the psychology of 2-D and 3-D audio environments, how humans distinguish important sounds from background noise, and the cognitive processes that are involved in processing textual information, no one has studied how the usable game interfaces may be applied to improve productivity.

A Sound Suggestion

I propose an effort that combines the talents of the screen-reader experts at the leading assistive technology companies with some of the game hackers and those in the research community to work together to develop a set of concrete user-interface paradigms that can be used to take the assistive technology field to the next level. Perhaps a summit meeting on the next generation of user interfaces for people who are blind or have low vision that includes all stakeholders would be a good place to start.

Can You Make Me Some Copies, Please?

We all know that there is an alarmingly high unemployment rate among people who are visually impaired, and many factors contribute to this problem. The inaccessibility of today's office equipment could be one factor, so we in the product evaluation lab at AFB's Technology and Employment Center in Huntington, West Virginia (AFB TECH), decided to evaluate office equipment. We interviewed local business leaders to determine the piece of equipment that is most important for their employees to be able to use in their daily work, and the copy machine was their overwhelming choice.

Today's copy machines have advanced beyond the simple duplication of documents and are now multifunctional devices with printing, fax, scanning, and e-mail capabilities to complement their traditional copy functions. This is the first in a series of articles evaluating the accessibility of these multifunctional units. This article discusses the large stand-alone units that have been commonly used in offices in the past few decades. Our next article will examine the smaller, less expensive desktop units that are available for businesses that may not need large workhorse copy machines. The final article in this series will go back to the large machines, focusing on accessibility solutions from Canon and Xerox that have been specifically designed to make their units more accessible and usable for people who are blind or have low vision.

The Interviews

AFB TECH collaborated with the local Workforce Investment Board to gather participants for our interviews. The Workforce Investment Board is part of the implementation of the Workforce Investment Act, a 1998 federal law that is designed to simplify and improve the delivery of employment services in the United States. The board consists of 30 local private-sector employers, local elected officials, and representatives of governmental agencies and local nonprofit organizations. Each member was sent a letter from the board chairperson introducing the AFB TECH project and asking him or her to participate in a short telephone interview. The telephone interviews were conducted by the AFB TECH staff.

After obtaining some basic information about the subjects' organizations, we asked them to rate the importance of the following 10 categories of office equipment: large multifunctional copy machines; business telephone systems; fax machines; printers; flatbed scanners; transaction/point-of-sale devices; postage meters; package and product labeling systems; networking equipment, such as routers, hubs, and firewalls; and personal digital assistants. We had them rate each category on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being not important at all and 5 being extremely important. To help clarify what we meant by important, we asked the interviewees how crucial it is for employees to be able to use each piece of equipment.

The large multifunctional copy machine scored the highest, with every interviewee giving it a 5 rating, so we chose to evaluate these machines for this article. The desktop printers, scanners, and fax machines were virtually tied for second place, so we chose desktop multifunctional units as the subject of the next article in the series. For those of you who are wondering, we omitted computers from this survey. Although computer access is obviously a prime component of the employment of people with visual impairments, a great deal of work is being done on this issue across the world. However, the accessibility of other office equipment has not been fully addressed.

Description and Evaluation

The multipurpose copy machines that are the subject of this article are the large 3.5-foot-tall stand-alone furniture-sized pieces of equipment that have been familiar fixtures in offices for the past two or three decades. These are expensive units, as our research found, costing from about $6,000 to more than $30,000, and are usually leased over a period of years by the user. These days, in addition to the standard functions of copying, collating, and stapling, they can be connected to an office's computer and telecommunications networks and provide printing, scanning, fax, and e-mail functions. When connected to networks, they can serve as a printer for all the office's PCs to use. Scanned images can be stored on your server, and you can use your optical character recognition (OCR) software to capture the text of these scanned documents. You can also use the copy machine itself to fax or e-mail the images.

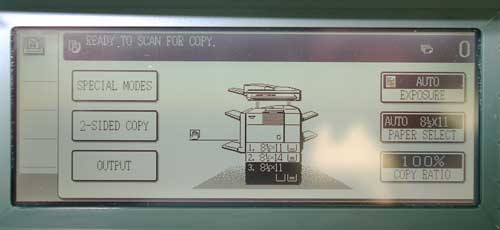

To begin our evaluation, we went to our own network server room and briefly examined the multifunctional unit that we were already leasing, a Pitney Bowes model DL270. We also leased another unit to evaluate, an Imagistics ZD35. The designs of these two units were similar, so we conducted research on the Internet to see if this style was commonplace. We visited two commercial retail copy centers, as well as the copy centers at two local universities, and every unit that we found, either online or in person, had a variation of the same design: a large document feeder tray on the top of the unit that is hinged in the back and lifts up to reveal the glass where the document's image is captured, output trays that are either on the left or right side, a front panel with doors for accessing and filling the paper trays, and a control panel. The control panel, which is used to access the various menus and functions, is at the top front of the unit and features a flat touch-screen display and a set of raised buttons, including a three-by-four telephone-style keypad. The touch-screen display is a small rectangular screen measuring roughly 3 inches by 6 inches.

Caption: The Imagistics ZD35 copy machine. The Pitney Bowes DL270 was similar in design.

To evaluate these units, we listed every task that is related to each of the multiple functions of each machine and determined how accessible each task was for people who are blind or have low vision. We determined whether there was any speech or tone feedback to support the user, evaluated the tactile and visual nature of the buttons and other controls on the unit, and looked at the accessibility of the available manuals and documentation. We did not evaluate the installation process because each unit is installed by the company that sells or leases it.

Results

The bottom line is that although a handful of functions on these two machines are accessible, the majority of the functions are not accessible and cannot be performed independently by people who are visually impaired. There are three main barriers to accessibility. First, there is no speech output functionality to convey information that is presented on the display screen to users who are blind. Second, the information that is presented on the display screen is not large enough for most people with low vision to read. Third, a flat touch-screen control is used to activate most of the features, and sighted people can simply press on the display screen to choose the various features. However, people who are blind or have low vision have no way to identify tactilely the proper places to press on the touch screen. In addition, it is not a practical solution simply to place braille or other raised markers on the touch screen because the screens and the location of the various controls change, depending on where you are in the menu system.

The rest of this article will examine the results of our evaluation of the Pitney Bowes and Imagistics copy machines. This discussion focuses on the accessibility of the tasks involved in the five major functional areas of these multifunctional copy machines: copying, printing, scanning, fax, and e-mail, but also covers miscellaneous accessibility issues.

Copying

The basic function of making a single copy of a document is accessible on both the Pitney Bowes and Imagistics units. You simply place the original document in the document feeder tray on top of the unit or directly on the document glass and press the large, round tactilely identifiable Start button, and the copy is soon delivered to the output tray on the side. With minimal assistance from a sighted person, it is easy to learn how to properly place your originals on the copier. Once you have learned this, placing the original in the feeder tray or directly on the glass can be accomplished tactilely and independently. You can also make multiple copies independently by simply using the number pad to type in the number of copies you want and then pressing the Start button. The keypad is a standard telephone-style keypad with easy-to-distinguish keys and a nib that is properly placed in the middle of the 5 key.

Caption: The Imagistics' controls.

These basic copying functions are the only ones that are accessible, however. All the other copying functions are inaccessible and require sighted assistance because you have to use the inaccessible touch screen to access all the other copy functions with these units. For example, if you are using the Imagistics and want your copies to be stapled, you press the Output icon on the touch screen and then press the Staple icon when a new screen appears. Although one could theoretically attempt to memorize the positions of the various icons on the various input screens, it would be nearly impossible to memorize everything for all the tasks that can be done on these machines, and there is no spoken feedback to confirm that you indeed pressed all the correct icons.

The other copy features and functions that are inaccessible because of the touch-screen interface include

- Sorting, which allows you to control how groups of output are arranged. For example, if you are making three copies of a five-page document, you can have the unit output three separate stacks, with each stack containing copies of all the original five pages, or five stacks, with each stack containing three copies of one of the original five pages.

- Two-Sided Copy, which allows you to copy two-sided originals onto one-sided output, or vice versa.

- Margin Shift, which allows you to control the size of the margins on the copies.

- Edge Erase, which allows you to have the copier ignore information on the edges of an original, such as margin notes.

- Center Erase, which allows you to ignore the middle between two pages when a book is open on the document glass.

- Dual-Page Copy, which allows you to recognize two separate pages and produce two separate pages of output when a book is open on the document glass.

- Booklet Mode, which prints out two pages on one sheet of legal-size paper, so you can fold the paper and have the binding in the middle like a small booklet.

- Text Resolution, which lets you adjust the text resolution of your output between photo quality and text quality.

- Zoom, which allows you to increase or decrease the size of the copy output.

Other inaccessible copy functions include numbering pages, making transparencies, inserting blank pages, and choosing the paper size for your output.

Printing

We have good news regarding the printing functions of these machines. When these machines are networked to your office's PC workstations, all the printing functions are accessible as long as your PC is equipped with a screen reader or screen magnifier. The copy machine simply acts like any other printer that you have connected to your PC. If you are printing a document, you simply use the print dialog box that you normally use with your word processor or other PC software, and you should have no problem accomplishing the task.

Scanning

Like the majority of the copy functions, the scanning process is inaccessible because you have to use the touch screen. Both machines that we tested have an accessible, tactilely distinguishable button that you press to bring up the image menu on the touch screen, but after that, the process is inaccessible. The touch screen is used to choose where to save the scanned image on your network server, and you have to choose a file format, such as PDF or TIF. You then press the Start button, and the image is scanned and saved.

Although the process is inaccessible, the scanning feature can still be useful to a person who is blind or has low vision. With sighted assistance to operate the touch screen, the document feeder can be used to scan dozens of pages of text at one time. Then, you can pull the image files from your network server and use your Kurzweil or OpenBook OCR software to recognize and read the text. We also successfully used the OCR capabilities in the Microsoft Office Document Imaging software that is part of the Microsoft Office suite of software.

Fax

The Pitney Bowes model that we evaluated did not have a fax function, so we evaluated the fax function only on the Imagistics. The fax function on the Imagistics is inaccessible because it relies even more heavily on the touch-screen interface than do the copying and scanning functions. You first press the same tactile button to bring up the imaging menu that is used for scanning on the touch screen. Then you use a multitude of touch-screen display screens to set it to fax mode, to dial fax numbers, and to store names and fax numbers for future use. Names and fax numbers are entered using a small onscreen keyboard, which is also inaccessible. After everything has been programmed, you put your document in the feeder and press the tactile Start button. You receive only a printout in 10-point font to confirm the success of the fax transmission, but no audible feedback. Incoming faxes were, of course, also only in print form. We did try to recognize some sample faxes with Kurzweil and OpenBook, but the quality of most of them was too poor for the text to be successfully recognized.

The e-mail process on both these machines is also inaccessible. It uses the same imaging touch-screen menu and again relies heavily on the touch screen for nearly everything, including entering and storing names and e-mail addresses. The e-mail process on these machines is used only for sending images, not for receiving or composing e-mail messages.

Manuals

Manuals and other documentation were available for the Pitney Bowes model only in print. However, in addition to print documentation, Imagistics also has manuals online in PDF format. We tested the files with the JAWS and Window-Eyes screen readers and found them to be accessible. However, there was an occasional unlabeled graphic. No braille documentation was available for either copier.

Miscellaneous Features and Functions

Loading paper can be accomplished tactilely, and with some minimal training, it is easy to learn how to load paper of various sizes and colors in each paper tray. However, changing the paper tray to use as the source for the output of your job is inaccessible because you need to use the touch screen.

Troubleshooting is inaccessible because error messages for malfunctions, such as paper jams, are presented only on the display screen. For instance, the screen may display the message "paper jam" with a blinking light next to the paper drawer that is the culprit.

Many organizations use an audit system to monitor and manage the use of their copy machines. This system requires you to enter your personal code or PIN number to use a copier. This process is accessible on both machines because the tactile number pad and Start button are used. However, if you are the manager of a copy center and need to monitor the use of the copier for cost purposes, you will not be able to read the usage reports. The process for producing the reports involves the touch screen, and the output is displayed only on the touch-screen display.

Low Vision Accessibility

The touch screens on these units presented the same barriers to accessibility for people with low vision that they do for people who are blind. The size of the information and icons that are presented on the display are too small for most people with low vision to see. Some people with low vision could use a handheld magnifier to enlarge what they see on the screen, but glare is often a problem, depending on the background lighting and the viewing angle. The text on the displays of both units was in a 12-point font, but the Imagistics, which is a newer model than the Pitney Bowes, had a brighter, higher-contrast screen, and the information was not as crowded. The Pitney Bowes had a tactilely distinguishable slider control for adjusting the contrast of the display, but it did not vary the contrast much. The contrast varies more on the Imagistics, but you have to adjust it using the touch screen.

Caption: The Imagistics touch-screen display is brighter and not as crowded as the one on the Pitney Bowes, but still has problems with glare.

Because of both the tactile and the visual nature of the buttons, the keypad and other control buttons that are not a part of the touch screen do not pose any barriers to accessibility for people with low vision. The colors of the buttons on both units contrast well with the background and their labels, and the labels are in 14- to 24-point font.

The zoom capabilities of these machines are for adjusting the size of the print on the copy output. This is certainly a feature that can be useful to a person with low vision, but it is controlled with the touch screen, which can be inaccessible to many people with low vision. Also, there is no way to zoom, or increase, the size of the information that is presented on the touch-screen display, which would greatly assist a person with low vision.

The Bottom Line

This evaluation has pointed out some major accessibility barriers to these large multifunctional copy machines. Although we did a detailed evaluation of only two machines, their user interfaces are representative of nearly all the large multifunctional units on the market. Other than the Xerox and Canon solutions that we will evaluate in a future article, none of the large stand-alone copy machines on the market has accessibility solutions for people who are blind or have low vision. So where does this leave us? At best, we are stuck with trying not to annoy colleagues too much as we say, "Can you make me some copies, please?" At worst, if using these machines is a major portion of a person's job, then it can severely affect a person's employability.

Caption: Even using a magnifier, the touch-screen displays on most copiers are not easy to see.

To be fully accessible to people who are blind or have low vision, all display information needs to be communicated through easy-to-understand speech output, and all the functions need to be operated through tactilely identifiable controls. Also, the display screens need to use larger fonts and feature contrast and zoom adjustability.

Next Steps