"Musings on the Evolution and Longevity of Accessible Personal Digital Assistants," in the November 2007 issue of AccessWorld, left the reader in suspense. The author—slightly winded from climbing all the way from the hotel lobby to the 47th floor—once more became ridiculously lost trying to locate the ever-elusive elevator bank that would have taken him back to his own floor. After 10 minutes of senseless wandering, he asked directions of other blind guests, who seemed as befuddled as he was by the misleading echoes generated by the seemingly irregular open spaces around him. Attempting—and failing miserably—to detect the subliminal sound of the elevator bell just below the threshold of any reasonable hearing, perhaps while slightly dissociating from stress, he imagined himself immersed in the virtual online universe of Second Life—the popular but totally inaccessible interactive three-dimensional (3D) Internet environment that is used by more than 9 million sighted subscribers worldwide. He had abundant time to reflect on the implications of his admittedly humorous accessibility plight inside the real hotel in a recently begun project—an early investigation of accessibility issues in the rapidly growing online world of 3D virtual environments. In a virtual world like Second Life, users—called citizens—all of whom are sighted, see themselves immersed in a visible representation of some reality—ranging from the mundane to the fantastic—where they may play interactive games; visit "islands" that are replete with buildings, museums, and people; attend college lectures; transact imaginary or real business; chat with other citizens; manipulate objects; or otherwise get hopelessly lost. Virtual worlds are undoubtedly a highly visual experience, yet, as early as July 2007, we already had good reasons to be confident that they can be made accessible to people who are blind more easily than may outwardly be expected.

The 3D Internet

The two-dimensional (2D) Internet is filled with standardized features that yield many forms of content in a variety of formats, including HTML, dynamic HTML, video and audio streams, interactive widgets, and secure transaction. The growing presence of major mainstream enterprises like IBM in virtual worlds, such as Second Life, may be a telling sign that the 2D Internet paradigm is showing accelerating evolutionary paths to 3D extensions—sometimes having emerging capabilities to emulate real-world situations. Admittedly, 3D Internet is in its infancy, and while it does not have many capabilities that real enterprises, schools and universities, governments, or even virtual e-tourists need to conduct business, a growing number of mainstream users find the overall virtual world experience far more immersive than that of the classic Internet. There is a growing opinion that virtual worlds may eventually replace the 2D Internet for many applications.

Accessibility Goals in Virtual Worlds

The 3D Internet's outwardly visual medium—containing complex and often absurdly detailed spaces, myriads of objects, a vast number of fancifully attired virtual "people," and a bewilderingly rich variety of modalities of interactions—presents unusual challenges for enabling access to users who are blind. Yet, we have reason to believe that there are many possible solutions to the access challenge. Virtual worlds are conceptual spaces that bear various degrees of correlation to the real world. By operating a mouse—or an equivalent device—sighted users move, learn, and interact by controlling a highly personalized iconic representation of self called an avatar. The often fancifully attired avatar is the user's point of regard—an extension of the 2D cursor into a content-rich 3D environment. The avatar has visible spatial and operational relationships with nearby objects and other avatars. Our challenge is to transform the visual operational paradigm into an equivalent nonvisual paradigm for users who are blind.

The ultimate goal of nonvisual accessibility to virtual worlds is to create an alternative paradigm that is both sensorially immersive and operationally effective. While a blind citizen of most any virtual world is shut out of the whole experience, we suggest that, in the future, it may be possible to create an experience for users who are blind that is as operationally efficient and emotionally fulfilling as that for sighted users. People who are blind may eventually control their virtual surroundings with predictive ease and comfort through alternative nonvisual operational methods, while enjoying a convincing sense of "being there" yielded by the spatial and tactile clues of a rich canvas of immersive soundscapes and semantically dense haptic stimuli. We suspect that totally immersive sensorial environments, by themselves, will remain insufficient to yield true operational accessibility and may, in isolation, be highly confusing to users who are blind. Rather, we are confident that sensorial immersion will eventually constitute a valuable augmentation of 3D extensions to more traditional software accessibility techniques that are derived from the familiar world of the 2D Internet. Some limitations of sensorial immersion are exemplified by the marginal accessibility of the self-voiced game Terraformers, discussed later, in which the admittedly interesting soundscape created by the virtual environment remains ancillary to the operational accessibility that is realizable by using a screen reader. In the real hotel where he resided during the 2007 convention of the National Federation of the Blind, the blind author remained lost and confused, while cutting only a dendritic path toward his goal in spite of the rich sonic and tactile feedback afforded by the environment. At each turn, he asked for directions—in other words, he sought a more deterministic method that would augment his senses and let him reach his destination.

The immediate goal of our project is to identify and develop a set of methodologies and components that are necessary and sufficient to constitute a minimal core of deterministic operational accessibility for people who are blind in virtual worlds. We believe that these new techniques can be successfully derived from existing software-accessibility paradigms. A blind citizen of a virtual world must be capable of doing the following:

- Determining spatial and operational relations between his avatar and nearby objects—in other words, query a "Where Am I?" function. The function may yield a text message, such as "Museum of Natural History. You are in the Cambrian explosion exhibit. You are surrounded by dozens of specimens of Opabinia regulis."

- Query objects' descriptions. For example, the citizen may ask what an "Opabinia regulis" is.

- Discover operational modalities for interactive objects—in other words, what can the citizen do to an Opabinia regulis?

- Operate on objects—in other words, activate one of the various operations defined for the object.

- Navigate and transport to other locations or move to the operational boundaries of different objects in the same neighborhood.

Admittedly, our goal is challenging. Yet in virtual worlds, many things already work in our favor. The real world has physical characteristics that impose operational limits. We cannot leap into the air and fly, walk through solid objects, change our size and shape in an instant, and certainly cannot teleport. If we had fallen down the infamous "blue stairs" in the real convention hotel, there would have been humiliating and potentially exceedingly painful consequences. Fortunately, none of these tawdry limitations need apply in a synthetic environment, a place where we—and a score of virtual world programmers—may all act as Dei ex machina and control and even bend the "forces of nature." Through early investigation, we may be starting to glimpse how implementations of virtual worlds can include accessibility features that enable users who are blind to participate as effectively, although perhaps not always as conveniently, as sighted users.

Applying 2D Internet Accessibility to a 3D Environment

Today, people who are blind can use the 2D Internet successfully. Textual web content and structural elements are made available and navigable through current screen-reader technology. If web accessibility guidelines are followed, even images may be described. Screen readers' conversion of web site content into synthetic speech or braille and users' ability to navigate a site with only the keyboard can often yield a satisfactory experience. It is our intent to extend this successful paradigm to yield an equally satisfactory experience for users who are blind in a virtual world.

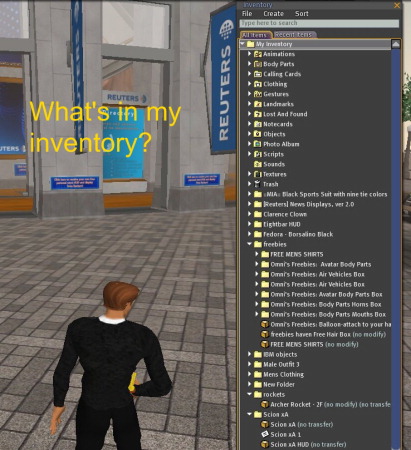

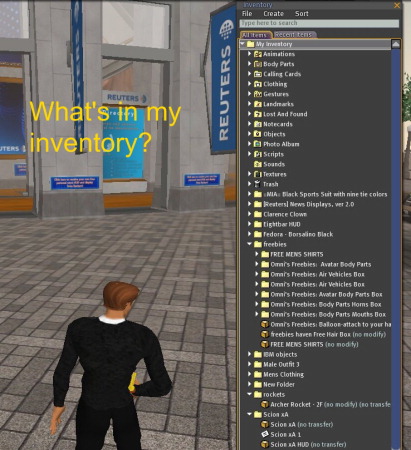

Serendipitously, virtual world graphical user interfaces (GUIs) often inherit a considerable set of legacy 2D widgets. There already are toolbars, dropdown menus, text-entry fields, selection buttons, sliders, and many other familiar GUI components (see Second Life screen shot below). Traditional 2D interactive objects also often appear when one clicks on—or moves the avatar over—any of the nearly countless denizens of the virtual world. Software-accessibility techniques for these commonplace GUI components are already well understood and may be addressed by existing screen-reader and keyboard-navigation techniques.

Caption: A screen shot from Second Life.

Yet, how can the native 3D content of a virtual world be accessed? How can a citizen who is blind—who cannot see his avatar or any surrounding virtual objects—ever interact with the other residents of virtual space or participate in any way to transact virtual business?

We may think of a virtual world as a GUI application that behaves much like a vast extension of a classic web browser. The avatar's general vicinity may be thought to be analogous to a web site, and virtual objects nearby can be thought of as the web site's content. We may regard the operation of moving to a different location in the virtual world to be analogous to opening a different web site or web page. Undeniably, though, there are glaring differences between the spaces of virtual worlds and the classic Internet. Among other things, not only are there the familiar dimensions of height and width inherited from the 2D web site paradigm, but these two dimensions are augmented by the Z axis of depth. Screen-reader technology and keyboard navigation must be enhanced and extended by technical breakthroughs specific to 3D environments. We may also develop 2D operational models of virtual worlds, where current screen-reading technologies can already operate.

Virtual World Accessibility Techniques

Accessible applications in 2D have an architected hierarchical tree structure. A window has toolbars, and toolbars have buttons and dropdown menus; a web site has pages, and pages contain headers, text paragraphs, forms, links, and other static and dynamic elements. Rather than attempt to interpret or recognize the myriad visible shapes and light patterns painted on the computer display, modern screen readers are capable of traversing and peeking into these underlying abstract tree structures. Names, roles, states, and other accessible attributes of many standardized 2D GUI components are queried by the screen-reading software and are then spoken or brailled as the user traverses them by keyboard.

By extension, the "engineering struts" behind virtual worlds may be abstracted as a set of hierarchical structures and directed graphs consisting of nodes and edges that represent abstract spatial relations, objects, and object properties. Virtual buildings have rooms, rooms have windows and doors, and doors lead from one room to another. Some virtual objects may exist in proximity to the user's avatar, while other objects and spaces are far away. Some may be purely decorative, while others may have a highly operational value. Some objects are completely static, while others may be highly interactive. Some are atomic, while others contain structural subcomponents. These relationships and characteristics remain undeniable challenges to current software-accessibility technologies, but constitute exciting opportunities for developing breakthrough accessibility techniques. It is interesting that some aspects of accessibility to virtual worlds may let us harness legacy software technologies that are already serving users who are blind in more traditional 2D applications.

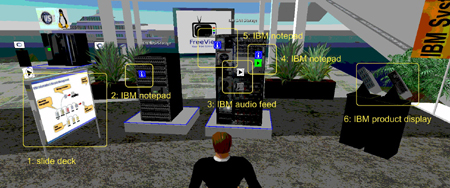

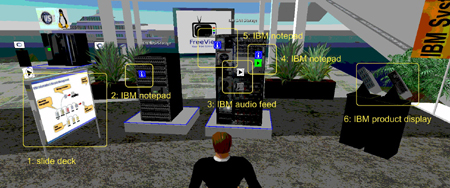

Imagine a scenario in which a user hits a hot key that causes the system to announce or braille a list of names of all the items within a 3-meter radius of the avatar (see avatar image below). This list may be numbered. The user may further specify that he or she requires only the names of nearby avatars while ignoring other objects or may prefer to learn about avatars and interactive objects while ignoring items that are likely to be only decorative. A key combination may be designed to move his avatar to the proximity of a specific item and activate it and then announce what operations are available in the particular context. In many virtual world implementations, a traditional and more familiar and accessible 2D menu may be associated with an interactive item and may be accessed by known means. In an exploratory mood, a user may direct the GUI to transfer one's avatar to the next frame or virtual sector of space to the north and generate a list of nearby items.

Caption: An avatar stands in front of an interactive nearby object.

As we mentioned earlier, this is somewhat akin to browsing 2D web sites, except that in the 3D Internet, one is immersed in regions of virtual space instead of observing flat and stylized web pages. A user who is blind may also customize the size and shape of the area of perception—in other words, may tailor the virtual horizon around the avatar. The virtual horizon of perception may be extended or reduced as desired via keyboard control to span a useful region of space for the particular situation. The horizon may span hundreds of yards in an open and sparsely populated field of flowers. Conversely, while exploring a clockwork mechanism, a user may prefer to reduce his or her virtual field of view to span just a few virtual cubic inches.

As with 2D accessibility, objects in virtual worlds should be designed to support a set of accessibility attributes to be made available to assistive technologies. Not only should there be a name and a description of an object, but role, state, and perhaps spatial orientation and category attributes must also be defined. In the doorway image below, for example, the door to the Reuters building is in the open state and faces south. Accessibility requires that a user who is blind who is facing north should be able to determine independently if he or she can pass through the door.

Caption: A doorway with an associated list of attributes.

Browsing the Virtual World

Wandering in an invisible environment is not a new challenge unique to 3D virtual worlds. Since the late 1970s, game players who are blind have sparred with text-based adventure games implemented for the Apple IIe and later for DOS with the sole help of an old screen reader. Who in the now-silvering crowd has not pitted his or her formerly younger wits against Cave and Zork? In the 1980s, some of us even enjoyed text-based MUD (multiuser dungeon) games in which the players interacted with an imaginary world via a command-line interface viewed on an ASCII character display. Simple keyboard commands were sufficient to navigate the world, and we received information about our surroundings through terse and often-glib bits of text that were verbalized by a Votrax synthetic speech synthesizer or displayed on a primitive refreshable braille display. We wandered inside vast mazes, found and picked up sundry objects, opened brown bags, extracted bottles of water, offered lunches "smelling of hot peppers" to ungrateful Wumpuses, and even wore cloves of garlic. We then vanquished trolls with a "bloody axe"—never try it with the "rusty knife"! As early as the days of MUDs, multiple players occupied the same virtual game space, and it was possible to engage in text chats with nearby players. The playing field was quickly leveled in a world where every one of us—blind and sighted alike—was served only terse and glib text as food for our wild and vivid 3D imaginations. In recent times, a modern version of the text MUD, called Terraformers, was developed by Pin Interactive. In this game, the graphic video display is said to be optional and can—at least in theory—be turned off. The game is marginally accessible to players who are blind through keyboard navigation and self-voiced audio cues alone, although more functional accessibility requires the use of a screen reader.

Modern general-purpose virtual worlds are not games per se, although they often contain some gamelike components. In games, players overcome deliberately introduced obstacles and are intentionally misled in their quest. Game designers cleverly tune the degree of difficulty to prevent completion before the game space has been thoroughly explored. Navigational solutions that serve well in a game world may not perform optimally for users who are engaged in business transactions in virtual worlds, where speed and expediency may be paramount.

The objective for virtual worlds that are tuned to business applications is usually of a more functional and pragmatic nature than that of a game. The design of the user interface should concentrate on ease of use and the efficient realization of a user's intentions. Tawdry limitations that are imposed by physical laws governing the real world may be happily glossed over. "Teleportation" to a meeting, for example, must be available to any user, regardless of his or her disability. Accessibility may require a blind user to control a simple dialogue box to enter the meeting location or its coordinates in the virtual universe. Then, by arrowing through a familiar-looking pop-up menu or tree view, the blind citizen may determine that a number of seats are nearby and may locate a seat that is in the "empty" state, perhaps even next to a friend. A keystroke may then move the avatar to the selected seat, and perhaps one more command may cause the same avatar to "sit" down. A citizen may scan the list of nearby avatars to determine if the meeting chairperson is present and then join a live discussion with other colleagues using an accessible text or voice chat.

A blind visitor to a virtual world must be able to perform an initial exploration of the virtual environment with maximum ease. One simple technique emulates real-world tethered navigation methods. The user who is blind may connect his avatar to that of a sighted friend or volunteer in "follow" mode. The "blind" avatar would then travel behind or alongside its guide in an oversimplified imitation of a blind person following a sighted guide. As in the real world, the tethered technique has its limitations; eventually, the blind user of virtual worlds will adopt much more independent travel strategies.

In many cases, interaction with a virtual object requires that the avatar be positioned within a field of proximity to the object of interest. "Dendritically stumbling" around the desired object is not noticeably effective (remember the infamous blue hotel stairs?). A simple keyboard command should be implemented to move one's avatar automatically to an object's operational radius, perhaps even in "ghost" or "flying" mode, if physical obstacles intervene. Optionally, a kinder and gentler pathfinding algorithm may gradually guide the user to her or his destination while passing around any "solid" obstacles. The synthetic nature of the environment opens up unlimited possibilities.

Metadata (Annotations) for Objects and Spaces

In many cases, the simple names and properties of surrounding objects may not satisfy our curiosity (What do you mean by "green toad"?). We may require a more comprehensive description of our object of interest. Ideally, the creators of the items, or perhaps even just some helpful visitors, have added descriptions that the user interface can verbalize or braille. A recorded voice description may even be provided. (Ah, so this is what the infamous Texas Houston Toad looks like!) These are data about data, or metadata, and in this article, we refer to them as "annotations." Annotations serve the same purpose as alternative text attributes and longdesc (a link to a file with a detailed description of the image) on images in the 2D Internet. Some areas in virtual worlds are prone to being heavily annotated with descriptions that enhance their usable accessibility to people who are blind. Other areas may remain relatively barren of annotations, representing "blind spots" for some of us. Annotating virtual objects alone is not adequate for effective spatial orientation. Spaces must be annotated as well. Any significant region, sector, or discrete volume of virtual space requires a label and a description.

In some cases, what is outwardly perceived to be an object may instead be constructed purely as a space, such as an open door or doorframe. A mechanism should be created to annotate objects and spaces interactively as needed by different users, regardless of the objects' ownership. The same object may receive multiple annotations—each with a unique digital signature identifying its creator. Users who are blind may then decide to accept annotations created only by a circle of "known" users. To reduce "virtual graffiti," users who are blind may optionally accept annotations from contributors who have a "reputation" above a certain threshold of "trust." Annotating activity may take advantage of social networking behaviors and generate useful information that may benefit all inhabitants of virtual worlds, regardless of their disabilities.

Cognitive Filters in the Virtual World

Sighted people in the physical world perceive hundreds of visual objects at a glance, but automatically ignore items that are not immediately important or operationally relevant or are otherwise not interesting. Similarly, a person who is blind in a virtual setting may need to establish selective perception filters to limit cognitive overload caused by overdetailed environments. There are essential operational properties of objects, but there is also a frequent abundance of decorative properties that have no operational value and can be safely ignored. We propose that virtual reality should first provide a full range of operational capability for users who are blind. Decorative aspects are secondary. It may not be essential to know that the avatar is standing in a virtual field of 4-inch-tall multicolored Portulaca flowers, the sun is shining 32.5 degrees above the horizon, and nearby avatars all look like feathered lizards—except for one who is impersonating a Texan Houston Toad. More important, what are the names of avatars surrounding the blind user? What are they chatting about? What objects can be manipulated in the vicinity, and what transactional options do they yield? "What is my location, and where are my friends?"

Multiple filtering modes should be provided to allow one easily to select different types of object awareness, depending on the setting or context. A social context may have perceptual requirements that are different from those of a business-related scene or an exploration activity. Some virtual world locations may offer special filter modes that visually impaired users may select to highlight particular features and activities. Adaptive user interfaces may be developed that learn a user's perceptual preferences in various types of situations over time.

Virtual worlds are used for a variety of purposes by sighted users, including training, education, collaboration, simulations of real-world scenarios, modeling, and the delivery of various forms of entertainment. How may these purposes apply to the accessibility requirements of users who are blind? We posit that exploratory research projects that are being launched in various accessibility research organizations, such as ours at the IBM Human Ability and Accessibility Center—are seminal to long-term accessibility for people who are blind and may, before long, enable the creation of elegant and interoperable standards for usable accessibility in virtual worlds.

The Bottom Line

We are confident that it is possible to provide a high degree of accessibility for people who are blind in virtual worlds. In our early research, we have attempted to identify some of the most promising software techniques among a wide range of possibilities. In the future, we hope that virtual worlds may serve as accessible models of the real world and that it may be possible to extend some virtual accessibility techniques to life in our physical space. The blind author cannot help musing that if he had access to a virtual model of the hotel where he so often got lost last July, and perhaps had the opportunity to explore it at some length in cyberspace, his wandering adventures in that factually hard reality may have been just a little more sure-footed.

If you have comments about this article, e-mail us at accessworld@afb.net.