****

The latest demographic research shows that 3.2 million Americans with diabetes are blind or have low vision. Because of the close relationship between diabetes and vision loss, the researchers at the AFB TECH product evaluation lab have kept track of the devices that are used to manage this disease, which is affecting more and more people. In the March 2007 issue of AccessWorld, we introduced the Prodigy and the Advocate, two small, inexpensive blood glucose monitors that are produced in Taiwan by Taidoc Technology. These monitors have some speech output to accommodate people who cannot read the screen, but the speech output is limited and does not communicate all the information on the screen. This article examines the SensoCard Plus and the new Prodigy Voice, both of which feature much more accessibility and usability for people who are blind or have low vision. It also briefly discusses the new Advocate Redi-Code and Prodigy Auto Code, both of which are similar to the originals but eliminate the need to calibrate the monitor to each new container of test strips. The sidebar accompanying this article, "Blind Entrepreneur Takes Action," describes efforts by Bay Area Digital to develop an accessible blood glucose meter. That company is headed by Chris Gray, a blind man who is the former president of the American Council of the Blind.

Readers who are interested in the accessibility of blood glucose monitors should be aware that the Accu-Chek Voicemate talking blood glucose monitor that we evaluated in the September 2002 issue of AccessWorld was discontinued by its manufacturer, Roche Diagnostics. Although the price of the Voicemate was high ($500), and the monitor was heavy and bulky compared to other monitors, it was at one time the most fully accessible monitor on the market. It is disturbing to see it disappear from the market without a replacement being introduced, and although a replacement unit may still come on the market, we have heard no news from Roche to support this hope.

For readers who are not familiar with the issue, here is some brief information from a previous AccessWorld article explaining the use of a blood glucose monitor to manage diabetes:

Because with diabetes, the body is unable to use and store glucose, or sugar, properly, it is necessary for people with this disease to monitor their blood glucose levels. You measure your blood glucose level by placing a small sample of blood on a test strip inserted into the monitor, and the monitor analyzes the blood and determines a blood sugar level. Using a blood glucose monitor to measure their blood glucose levels enables people to keep these levels within a normal range by taking a dose of insulin or eating a certain food. When not managed properly, diabetes can be a deadly disease, attacking several internal organs, including the heart and pancreas, as well as the eyes. Blood glucose meters have revolutionized diabetes care by allowing individuals with diabetes to control their condition more actively. If you are not able to operate the meter and read the results, the meter is not usable, and you have a much lower chance of keeping the ravages of diabetes at bay.

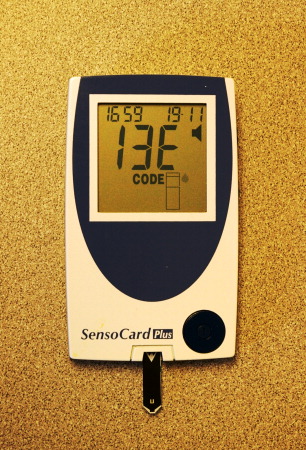

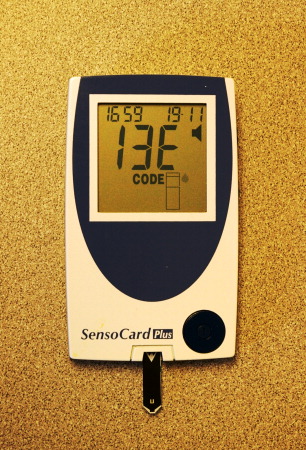

The SensoCard Plus

The SensoCard Plus is distributed by BBI Healthcare in the United Kingdom and is manufactured by a Hungarian company called Electronica 77. It is priced in Europe at £49.99. BBI is in the middle of the cumbersome process of gaining approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), so the SensoCard Plus is not yet available in the United States. However, BBI hopes to have FDA approval soon, and AccessWorld will inform you when it does.

Caption: The SensoCard Plus.

The SensoCard is a thin, credit card-sized monitor with built-in speech output that supports all its functions. It weighs 2.5 ounces and measures 3.5 by 2.2 by 0.3 inches, with a small speaker protruding an additional 0.25 inches from the back of the bottom panel of the monitor. It has a 1.3-inch-square black-and-white LCD (liquid crystal display) screen and only three control buttons. The round main control button is below the display screen on the right, and there are two arrow-shaped Up and Down buttons on the right side panel. There is a small slot in the front panel of the monitor for inserting a test strip and another slot on the bottom of the left side panel for a code card strip that calibrates the meter with each new container of test strips. There is an infrared data port on the back panel for transferring data to a PC, but there is no headphone jack.

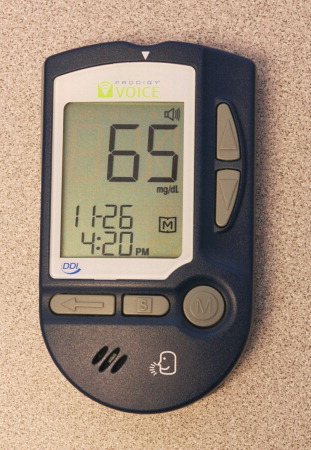

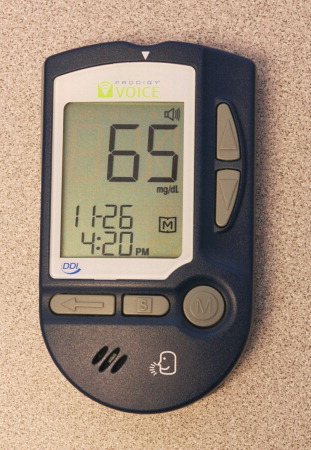

The Prodigy Voice

Priced at $79.99, the Prodigy Voice is distributed by Diagnostic Devices and is manufactured in Taiwan by Taidoc Technology. It came on the U.S. market on November 19, 2007, and its speech output supports every function of the meter, far surpassing the accessibility of the original Prodigy, which we reviewed in the March 2007 issue of AccessWorld. The Prodigy Voice weighs 2.7 ounces and measures 2.0 by 3.5 by 0.8 inches. The front panel has a 1.34-inch by 1.75-inch monochrome black-on-gray display, with three control buttons just below. The round Power button is on the right and is larger than the other two buttons. It turns the meter on and off and is also used to enter Memory Recall mode. The Settings button is in the middle and has a smaller, triangular shape. The Repeat button is on the left and replays the last spoken message or test result. The speaker is just below the buttons. On the right side panel are two triangular buttons pointing up and down that are used to adjust the various settings and to scroll through the various readings in memory. The Eject button, on the top of the left panel, allows you to eject a used test strip easily and safely without touching it. The standard 3.5 millimeter ear phone jack, near the bottom of the right side panel, allows you to use a headphone for privacy or to connect a speaker to amplify the speech. The data port, just below the ear phone jack, allows you to download the meter's test results to a computer using Prodigy's download software.

Caption: The Prodigy Voice.

How Did We Evaluate the Monitors?

As with our previous evaluations of blood glucose monitors, we first examined the tasks involved in performing the basic function of obtaining a blood glucose measurement and evaluated how easily a person who is blind or has low vision could perform each task. We looked at each task and determined if it could be performed by touch alone or if vision would be required. We then did the same with other tasks related to several other features and functions of the monitors. We also looked at how easily a person with low vision could read the display information and perform the other tasks that require vision. In addition, we evaluated the accessibility of the print and electronic manuals.

Results

Obtaining a Blood Glucose Measurement

The process of obtaining a blood glucose measurement is fully accessible on both the Prodigy Voice and the SensoCard, with speech output supporting the process the entire way and speaking your test results. Both feature high-quality recorded human speech, rather than synthesized speech, and both speak test results in only 5 seconds. Both also alert you if your reading is out of the normal healthy range. Both have control buttons that are easy to identify tactilely, and both require a small sample of blood, with the SensoCard requiring 0.5 microliters and the Prodigy Voice requiring 0.6 microliters. Both use strips with capillary action, which pulls your blood sample into the strip, eliminating the need to place a large hanging drop of blood onto the strip. The strips also stick out away from the meter, which greatly reduces the chance that you will need to clean blood from the meter. The Prodigy has a handy Eject button, so you can safely dispose of used strips without having to touch them.

Both meters use strips with a tactile notch for orientation purposes. The blood application end of the SensoCard strips is pointed, which helps to ensure that you do not put the strip in backward. The SensoCard alerts you if you accidentally inserted a used test strip, but it does not alert you if you inserted a strip upside down. It speaks the same message prompting you to apply blood, so you may inadvertently waste the test strip. The Prodigy Voice does not alert you of either of these errors, but if you use or incorrectly inserted a test strip, it will not prompt you to apply blood, so you will know something is wrong.

The Prodigy has a Repeat button to announce your reading again if you did not hear it the first time, and the SensoCard will repeat your reading if you press the Up button before you remove the test strip. Both meters can provide results in both milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) and millimoles per liter (mmol/L), and changing from one type of measurement result to the other is accessible on both meters. Both meters play a shutdown tune and turn themselves off automatically if they are not used for a short time.

Accessing Past Readings in Memory

The memory function of both meters is fully accessible and is supported entirely by speech output. The SensoCard can store up to 500 readings and provides 7-, 14-, and 28-day averages. The Prodigy Voice can store up to 450 readings and provides 7-, 14-, 21-, 30-, 60-, and 90-day averages. It is easy with each meter to scroll through the averages and the individual readings, voicing the glucose level, date, and time of each reading. You can also clear the memory data independently on each meter, but the meter clears all the readings from memory, and you cannot delete one reading at a time.

The SensoCard allows you to mark an abnormal reading, such as one taken after heavy exercise or a large meal, that may throw off your averages. Marked readings are not included in your averages, but you must mark them immediately after taking them. These readings still appear when you scroll through memory, but the speech output tells you that they are marked results.

Coding the Test Strips

Most blood glucose monitors require that you set a code number to calibrate them to the test strips every time you open a new container of strips, and doing so is usually inaccessible for people who are blind or have low vision. However, the Prodigy Voice eliminates this step. It has an auto code feature that automatically codes the meter when a strip is inserted and eliminates any human error involved in coding strips.

The SensoCard still requires coding for each new bottle of test strips, but it uses a code card, eliminating the need to code the meter manually. You simply turn the monitor on and press the Down arrow after the welcome greeting. The voice says, "Code set menu. Insert the code card." You then insert and remove the code card in one fluid movement in the slot in the bottom of the left side panel. The card sets the code and reads aloud the code setting. The code card comes with each new bottle of test strips; it is a small plastic strip of paper about 1.5 inches long by half an inch wide and has a squared end that is inserted and a rounded end that you hold to insert it. You can code manually with speech support if you lose the strip, but you may need to get sighted assistance to read the code from the strip bottle.

Settings

The settings functions of both meters are fully accessible, with speech supporting the entire process. The function is called the Function menu on the SensoCard, and you are able to perform a system check, set the calibration code manually, upload your test data to a PC, set the time and date, delete your test memory, choose between mg/dL and mmol/L as the measurement unit, and set the voice to speak English or German or to be silent. The Prodigy settings include time and date, measurement unit, speech volume, and the delete memory function. The fact that the Prodigy's Settings button is no longer hidden in the battery compartment is another improvement over the original Prodigy.

Performing a System Check

An occasional system check is recommended when using most blood glucose meters to ensure proper performance. You may want to do this test after you have dropped your meter or left it in an extremely hot or cold environment, such as a parked car.

With the SensoCard, you use the talking menus and insert the check strip that comes with the meter. The meter performs a measurement and displays the result of the test. If the value spoken is within the range indicated on the label affixed to the pocket in the carrying case, then the meter is performing properly. The test is accessible, but you need to learn how to orient the check strip properly and to make a note of the range indicated on the pocket in the carrying case. If you lose the check strip, the test can also be performed with a regular test strip and the control solution available from the manufacturer.

The Prodigy Voice has what they call an Auto System Function Check, so you do not use a check strip. Instead, you use a regular test strip and the control solution from the manufacturer. The control solution bottle shows the range in which the test result should fall if your meter is performing properly.

Download Software

Both meters have free software available, so you can download your results to a PC. The Prodigy Voice requires a cable accessory to connect the monitor to a PC, and the cable is available from the manufacturer's web site. The SensoCard requires its "Light Link" adapter, which creates an infrared link to the meter. The software creates charts and graphs for monitoring your test history and prepares reports that you can send to your health care provider, so he or she can track your blood sugar levels over time. We used both Window-Eyes and JAWS to test the accessibility of the SensoCard software, but the Prodigy Voice software was not yet available at the time of our testing. Although Diagnostic Devices, Inc. told us that the Prodigy voice's download software was designed specifically to work with screen readers, we cannot yet confirm that.

Caption: An AFB TECH intern connecting the SensoCard to a PC via infrared.

The SensoCard software, called DiaTransfer, uses a nonstandard installation procedure that is inaccessible to screen readers because of unlabeled graphical buttons. After we got sighted assistance to install the software, we took a look at the software manual. Although the manual is an untagged PDF document, it was mainly accessible, except for some mouse-based instructions. The software itself, though, was not accessible using a screen reader. A highly skilled user of screen readers may be able to glom some usable information from the software, but there are far too many accessibility problems, such as unlabeled buttons and edit fields, to consider this software accessible or usable for people who use screen readers.

Our testers with low vision had success using ZoomText to use the software. The ZoomText tools to change magnification and screen colors worked fine. Although the speech functionality of ZoomText did not work perfectly, the ZoomText Speak It tool spoke the onscreen text much better than the screen readers did.

Warnings and Error Messages

The Prodigy Voice speaks all warnings and error messages that appear on the meter's display screen, such as a warning that your blood glucose measurement is too high or too low. The SensoCard also speaks warnings and error messages. With some of the messages, it just speaks the letter or number of the error, such as "Error C," and you have to look in the manual to determine what that code represents. At other times, it also speaks what the warning message means, saying, "Error 7: insufficient blood." Thus, it may be a good idea to keep a handy cheat sheet in braille or large print in the SensoCard's carrying case.

Battery Replacement

Both the Prodigy Voice and the SensoCard speak to warn you that the batteries are low and that it is time to change them. You can change the batteries independently on both meters, but it is a bit easier to do so with the Prodigy, which uses two AAA batteries, which are easier to orient tactilely than are the two small round, silver watch-style batteries that the SensoCard uses.

Documentation

Each meter comes with a print manual in standard 12-point font, which is too small for most people with low vision to read. Each also has an electronic version of the manual available in PDF format. Although both are untagged PDF documents, only the SensoCard manual works well when you use a screen reader. The SensoCard also provides instructions that have been written with the blind reader in mind, providing good descriptions of the meter and how to perform tasks nonvisually. The Prodigy Voice PDF manual has some structural problems and does not work well with screen readers. Although most of the text can be read with a screen reader, the manual was not written with the blind reader in mind and does not provide good descriptions of the meter or how to perform tasks nonvisually. We also had to experiment with the reading order in Adobe Acrobat when we read the Prodigy Voice manual.

Low Vision Accessibility

Both monitors have a monochrome display screen with black text and icons against a gray background. These low-contrast displays are similar to the old calculator display screens and would not be preferred by most people with low vision. On the Prodigy Voice, the icons, such as the low-battery icon and the frowny face indicating an out-of-range test result, are too small to be seen by most people with low vision, but some of the text is displayed in large print and could be read by our testers with low vision. The results of the blood glucose measurement are in a 60-point font, and the time and date are in a 26-point font. However, the text indicating the type of measurement, such as milligrams per deciliter, is in a 6- to 8-point font. The SensoCard consistently uses large fonts, with font sizes ranging from 18 points to 60 points, which can be easily read by most people with low vision.

As far as the visual nature of the other physical characteristics of the monitors, our testers with low vision said that the labels on the buttons are too small for most people with low vision to read. Also, the button labels on both monitors are nearly the same color as the buttons themselves, providing no contrast to accommodate the reader with low vision. However, because the buttons are easy to identify tactilely, it is not as important an issue as the visual nature of the display screen. Of course, the speech output on these meters will accommodate a person whose vision is such that he or she cannot read the display screen.

The Prodigy Auto Code and Advocate Redi-Code

The Prodigy Auto Code and Advocate Redi-Code are two other blood glucose meters that came on the U.S. market in 2007. They are virtually the same as the Prodigy and Advocate evaluated in the March 2007 issue of AccessWorld. The main difference is that they both have added the convenience of an audomatic coding system, eliminating the need to calibrate the monitor to each new bottle of test strips. Although that convenience is also an accessibility advancement, nothing else has been done with these two monitors to increase overall accessibility. Although they speak to guide you through testing your blood and read out your measurement levels, they do not have near the overall accessibility as the SensoCard and the Prodigy Voice.

The Prodigy and Advocate Duo, which also came on the market in 2007, are basically the original Prodigy and Advocate meters combined with talking blood pressure monitors. However, we did not evaluate them for this article because the parts of the blood glucose meters are exactly like the ones we evaluated in the March 2007 issue of AccessWorld. Also, they are wrist-type blood pressure monitors, which are not considered to be as accurate as the over-the-arm cuff-type monitors that we evaluated in the September 2004 issue of AccessWorld.

The Bottom Line

The Prodigy Voice and the SensoCard are both highly accessible and are much-needed additions to the blood glucose meter market. They are smaller; cheaper; faster; and, in general, much better than anything we have had in the past as far as accessible blood glucose monitors. Although we are impressed with both meters, each has an advantage over the other here and there. We consider the Prodigy Voice to be a slightly more accessible and usable meter. The most obvious advantage of the Prodigy Voice is that it is available in the United States now, while the SensoCard is still awaiting FDA approval. The Prodigy Voice's earphone jack is a major advantage over the SensoCard, allowing you to use a headset for privacy or for connecting a speaker for amplification of the speech output. You can also adjust the volume on the Prodigy Voice, but not on the SensoCard. Although the SensoCard's volume is easy to hear in normal settings, it may be too loud in a setting where privacy is desired or too low in a noisy setting. The Prodigy Voice's Auto Code feature is another advantage of the Prodigy Voice, eliminating one step in the process and any human error that may occur when coding a new bottle of test strips. When you use the Prodigy Voice, you know if you have inserted a test strip improperly, which is not the case when you use the SensoCard. The Prodigy Voice's accessible download software is another advantage for those who are interested in tracking their measurement data on their PCs or e-mailing their data to their health care providers. Finally, the Eject button is a nice convenience found only on the Prodigy.

We want to stress, however, that we like both these new meters, and the SensoCard has some advantages of its own. The major advantage of the SensoCard is its accessible and well-written electronic manual, which many people may consider the most important factor. The SensoCard is also slightly smaller and more portable and uses large fonts more consistently on its display screen. Finally, it allows you to mark abnormal readings, so they are not included in your weekly and monthly averages.

Both BBI and Diagnostic Devices should be applauded for their efforts in making accessible blood glucose meters and for seeking input from many people who are blind or have low vision who will use the meters. In addition to contact with the American Foundation for the Blind, Diagnostic Devices worked with the National Federation of the Blind in developing the Prodigy Voice, and BBI is involved with the Royal National Institute of Blind People in the United Kingdom. We are happy that these small companies have brought accessibility to the market of blood glucose meters, but we would also like to see the large pharmaceutical companies that have dominated this market for the past several decades do something to serve people who are blind or have low vision. We also would like to see some movement toward accessibility with the other devices that people with diabetes use, such as insulin pumps, insulin pens, and home blood pressure monitors. Certainly, the 3.2 million Americans with diabetes who have some degree of vision loss are a large enough market to attract some interest from the manufacturers. What do you say, Roche? Johnson and Johnson? Abbott Labs?

Product Information

Products: Prodigy Auto Code, Prodigy Voice, and Advocate Redi-Code Blood Glucose Monitors..

Manufacturer: Taidoc Technology, Dot 4F, No. 88, Section 1, Kwang-Fu Road, San-Chung, Taipei County, Taiwan; phone: +886-2-6635-8080, Ext. 368; e-mail: anthony@taidoc.com, technical service: tony.cc1128@msa.hinet.net, customer service: service@taidoc.com; web site: www.taidoc.com.

U.S. Distributor of the Advocate: Pharma Supply, 3381 Fairlane Farms Road, West Palm Beach, FL 33414; phone: Customer Care Center, 866-373-2824; e-mail: info@pharmasupply.com; web site: www.pharmasupply.com.

Price: $46.99.

U.S. Distributor of the Prodigy: Diagnostic Devices, 5900-A Northwoods Business Park, Charlotte, NC 28269; phone: customer service, 800-366-5901, or technical support, 800-243-2636; e-mail: customer service, customerservice@prodigymeter.com, or technical support, techsupport@prodigymeter.com; web site: www.prodigymeter.com.

Price: Prodigy Auto Code $39.99, Prodigy Voice: $79.99.

Product: SensoCard Plus Blood Glucose Monitor.

Distributor: BBI Healthcare, Unit A, Kestrel Way, Garngoch Industrial Estate, Gorseinon, Swansea, SA4 9WN, Wales; phone: 01792-229-333; e-mail: info@bbihealthcare.com; web site: www.bbihealthcare.com.

U.K. Distributor of the SensoCard Plus: Royal National Institute of Blind People, 105 Judd Street, London, WC1H 9NE, England; phone: 020-7388-1266; e-mail: helpline@rnib.org.uk; web site: onlineshop.rnib.org.uk.

Price: No U.S. price currently available.

This product evaluation was funded by the Teubert Foundation, Huntington, West Virginia. We also acknowledge the valuable assistance provided by Marshall University intern Charles Wesley Clements.

****

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

****

View the Product Ratings as a graphic

View the Product Ratings as text

Blind Entrepreneur Takes Action

Growing tired of the ongoing lack of attention paid to the accessibility of diabetes devices by the big pharmaceutical companies, blind entrepreneur Chris Gray decided to do something about it. Chris Gray is the former president of the American Council of the Blind, and his company, Bay Area Digital, is working on solutions for making blood glucose testing more accessible for the millions of people with diabetes who are blind or have low vision.

Gray visited AFB TECH in summer 2007 to discuss the work of Bay Area Digital. He showed us his prototype for an accessible blood glucose meter and another prototype for a little gadget that makes it easier to place your blood sample properly on the glucose meter test strip.

Gray told us that when he approached the big manufacturers of blood glucose meters about accessibility, he learned that the profit potential of the market of consumers who are blind or have low vision does not interest them. He said that they build a minimum of 7,500 to 10,000 meters per day, and our market is just too small to make a difference. With this point in mind, Gray's business plan is for Bay Area Digital to work on the accessibility and the manufacturers to worry about the accuracy and other competitive factors of the meters. He brought this idea to the Diabetes Care Division of Abbott Labs, makers of the Freestyle Freedom blood glucose meter. Bay Area Digital, along with the American Council of the Blind's Diabetes in Action division, is now collaborating with Abbott Labs to bring accessibility to the Freestyle Freedom. Gray has also asked for AFB TECH input on his prototype, which we are more than happy to provide, and AFB also fully supports his efforts to bring more accessibility to the diabetes market.

Gray said that he likes the Freestyle Freedom for a couple of important reasons. First, the meter does not have to be calibrated for each new bottle of test strips, which is similar to the auto code feature of the Prodigy Voice. Second, and more important according to Gray, is the auto-fill feature of the Freestyle Freedom's test strips. With auto-fill strips, the meter does not take a reading until the strip has the right amount of blood, greatly increasing the accuracy of the test and minimizing the need for multiple testing.

Gray first showed us his prototype for the gadget that makes it easier to place a blood sample properly on the glucose meter test strip. It is a simple plastic ring that attaches to your finger with a small band. It guides your lancet device to a spot on your finger and then guides the test strip to the same spot.

Gray's prototype blood glucose meter consists of the Freestyle Freedom connected via a serial cable to a laptop computer. The laptop runs Bay Area Digital's prototype software, which controls all the meter's functionality and speaks all the information that is displayed on the meter. It has other voice prompts guiding you along the way, and it is controlled entirely by keystroke commands.

Examining the prototype in the AFB TECH lab, we found that it provides access to nearly all the features and functions of the meter. It also adds an alarm feature to prompt you to check your blood sugar level throughout the day. Of course, Gray asked us to provide feedback and to let him know of any suggestions we may have. The only thing we really think he should add, as far as how the interface functions, would be a voice prompt telling you when the battery is low and needs to be replaced. Another minor issue involves entering digits when setting the alarm, the time, and the date. The software does not echo the digits as you enter them or delete the digits if you make a mistake. However, it does repeat the settings when you finish, and because it is a simple task, it is no problem to reenter the settings if you hear that you made a mistake.

Our biggest concern, which Gray agrees with, is portability. Being tethered to a computer is fine for testing at home, but because aggressive diabetes management requires several tests throughout the day, it is not always practical to carry a laptop with you everywhere. Of course, this is just a prototype, and Bay Area Digital's ultimate goal is to build this functionality into the meter itself or perhaps into a small unit that attaches to the meter. On November 13, Gray received notification that this integration will be funded for six months by the National Science Foundation. So, there should be a lot more to this story before long.

Return to article, or use your browser's "back" button.